Poems, Pictures, and a Reflection

Jamie McKendrick

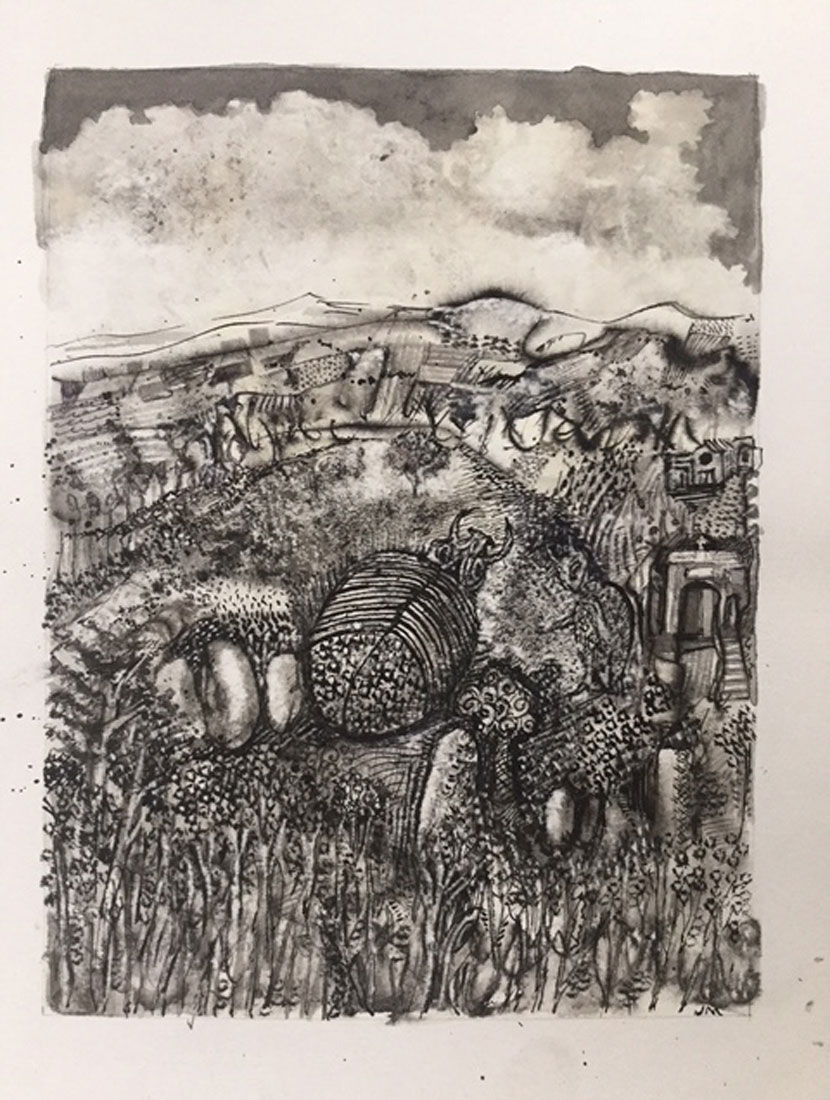

The Thurn-Harrier

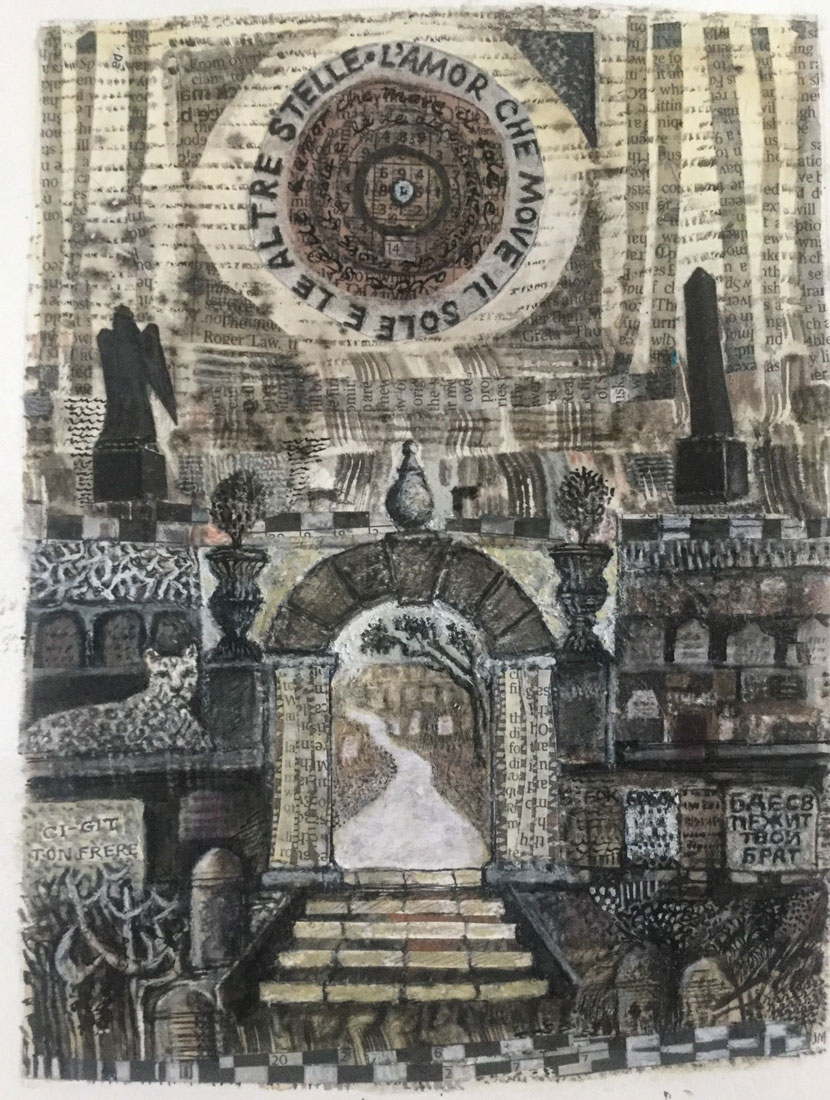

L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle

Jamie McKendrick is a poet, essayist, translator, and artist. His last book of poems was Anomaly (Faber, 2018) The Years, a pamphlet of poems and paintings, will be published by Arc in the autumn. The Foreign Connection, a book of essays on poetry and art, will be published soon.

Editor’s note: Jamie McKendrick’s life as an artist, and the fact that it’s less known than his achievements as a poet and translator, is the sort of branching out that’s of interest to ‘literary activism’. I suppose he’s the ‘other’ in the title of the essay below. The ‘other’ suggests an interlocutor, and an interlocutor a conversation, which, as the note to the launch event says, is also of interest to this website. McKendrick himself brings in that notion (‘to converse’) at the end of his essay, in relation to the poems and pictures above.

The Professional and the Other

The self-taught artist is a semi-respectable being like an itinerant preacher or an inventor with a patent; or perhaps an islanded figure like Elizabeth Bishop’s Crusoe who with melancholy glee cries out ‘Home-made, home-made! But aren’t we all?’ Or so it might seem, but the reality is and has probably always been far more ambiguous than that. Paul Gauguin was a stockbroker before taking up his brushes; Vincent Van Gogh an art dealer then a missionary; Francis Bacon an itinerant gambler, not that he stopped being that. Georges Braque is an in-between figure: he was trained as a house painter, like his father and grandfather, then studied in the evenings for two years at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Le Havre. His artisan skills were effectively employed in his art – from wallpaper in collage, to mixing sand with his paint. Eileen Agar again hovers between, having studied part-time at the Slade School of Art. The game could go on. Paul Nash: Slade; his brother John: though fraternally encouraged, self-taught. Bhupen Khakhar: late-starter, self-taught; his friend Howard Hodgkin: Camberwell and Bath Academy of Arts…

Further back, we might think William Blake was just such an eccentric and islanded artist, but though he left school at the age of ten, he attended Pars’ school for drawing, served an apprenticeship as an engraver with James Basire, and later briefly attended the Royal Academy, so his training was far from rudimentary. The archetypal outsider artist, Alfred Wallis took up painting some time in his sixties, and used the limited range of boat paints to hand, usually on bits of primed board. He worked on his table rather than an easel, horizontally rather than vertically, so it’s odd how vertiginous some of his seascapes are. He had little understanding of, or use for, perspective. And yet no one who has seen his paintings could deny his singular, sea-haunted, searing vision. Several St. Ives painters such as Ben Nicholson (Slade-trained, and the son of two famous painters) not only appreciated his art but learnt from it as well. Something of the same celebrity attached itself to the Customs official Henri Rousseau among the Parisian artists of the previous generation. The latter is often referred to as a ‘primitive’, perhaps in dual reference to his untaught status and to his frequent subject matter of tropical jungles. Just how problematic the term ‘primitive’ is in Western art history doesn’t need to be explored here, but contact with West African and Oceanic art has left a large and liberating imprint on twentieth-century European art. As one example, the rich confluence of styles that emerged in the Sepik valley of New Guinea, and the variety of media employed, would confound any stereotypical view of that work, or any notion that ‘tribal art’ lacks individuality. John Guiart’s introduction to the long out-of-print Oceanic Art (Fontana, UNESCO, 1968) argues this point passionately and persuasively.

My great-grandfather worked on the railways, was a trade unionist, and died of consumption at thirty-five or six. Somewhere along the way he found time to learn how to paint. Did he attend art classes in Glasgow or Newcastle? How could he afford canvases and oil paints? I’ll never know. All I have is the surviving evidence of his work, which is one small sketchbook, headed Glasgow, Aug. 14, 1880, with smudged but fluent pencil drawings of figures and landscapes, and three oil paintings. One of these is a portrait, possibly a self portrait, of a pallidly clerkish figure, well executed but rather grim. The second depicts a dog on a hearth rug which is – I’ve only just discovered, with a flicker of disappointment – a copy of Landseer’s Sleeping Bloodhound. It’s such a loving depiction, we always assumed it was his dog. He has subdued the original’s flaming scarlet highlights and turned the red carpet green (a play on Macbeth or colour-blindness?) but it’s deft apprentice work. The third, the best, dated 1890 – the year of his death, is a large landscape with a stretch of a Northumbrian river (the Coquet, near Rothbury?) that wouldn’t look amiss in any civic art gallery. Reflections of the tall overhanging beech trees and passages of brilliant white impasto make the surface of the water alive. There was another, now lost, large-scale painting I remember from my youth of two agricultural labourers, man and woman, in a barley field, looking somewhat heroic in the style of Jean-François Millet’s Angelus, but without the religiosity or sentimentalism. Like the landscape, a work of considerable skill.

Northumbrian River by Thomas McKendrick

Forgive me this atavistic interlude but I’ve had a lifetime to look at his work and it has often prompted questions for me. A self-taught artist perhaps, but in no way a ‘primitive’. The possessor of a talent which, had it been nurtured by money, time and training, and not been cut off so young, might well have flourished. He seems to have known what and how he wanted to paint, and his sketchbook is full of colour notes and clearly shows the slow accumulation of images preparatory to painting.

Lately, I’ve become interested in that old-style activist, Ernest Jones, a Chartist poet who wrote in the idiom of Shelley’s directly political 1819 poems, and a friend of Karl Marx, whom he apparently persuaded to reconsider his earlier notion that colonialism might serve progress. Jones spent years in prison, two of them in solitary confinement, for sedition, advocating Irish independence. He also wrote articles agitating for the sepoys to throw off their masters in the East India Company. On the evidence of the two surviving drawings of his in the British Library https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/drawing-by-ernest-jones-chartist he was a finer artist than poet. I wish Tom Lubbock, in a sequel to his seminal book English Graphic, were still here to think about these two extraordinary cityscapes – one lowering, hellish and English, the other serene, idyllic and Grecian.

Elizabeth Bishop, an unusually gifted occasional painter who would never have thought of herself as an artist, was warmly responsive to the primitive in art, as can be seen in her appreciative essay on the Cuban painter Gregorio Valdes, a neighbour of hers in Key West. After she made her first purchase of one of his works encountered in a barber-shop ‘for three dollars’ she took it home:

My landlady had been trained to do ‘oils’ at the Convent. – The house was filled with copies of The Roman Girl at the Well, Horses in a Thunderstorm etc.– She was disgusted and said she would paint the same picture for me, ‘for fifteen cents.’

Those three short sentences brilliantly compress much matter concerning a perceived hierarchy of art, the numbing hand of convention, as well as sardonically foregrounding certain commercial considerations.

My own intermittent forays into art are poised uncertainly between the trammelled technique of a self-taught artist and someone who with a little instruction has gained some understanding of colour, tone and line, and has had copious opportunity to study the art of others. (I reviewed art for some ten years.) Am I then a ‘primitive’ adulterated by a little knowledge? Would more training have served me better or even less? These questions are futile, and don’t in the least distract me when I’m at work on a picture, or only in occasional moments of frustration at being unable to attain an effect I’m striving for. For the most part the activity is angst-free and experimental. The experiments that are evident failures are not in any way crushing, but often seem to help with subsequent efforts. Maybe that’s because I can fall back on, or have as an alibi, my main – but not that much less intermittent – activity as a writer.

This leads me to wonder whether the category of ‘naive’ or self-taught poet (aren’t we all?) exists as it does in art, however problematically. John Clare (who might have begun with rural ballads but then absorbed everything he needed from past and contemporary poetry)? Samuel Greenberg (whom Hart Crane called ‘a Rimbaud in embryo’ and whose work he collaged into ‘Emblems of Conduct’)? A little further afield, Dino Campana? Then there are the knowingly naive poets such as Edward Lear, Stevie Smith, Ivor Cutler or Aldo Palazzeschi…Already the demarcations blur, the categories, as with art, proliferate. What has emerged in the UK for the last ten or so years, and in the US for way longer, is a new category of professionalised poets, who have come through creative writing departments, themselves loosely modelled on art colleges. But what is being learnt there or, for that matter, in art schools? Once artists might have learnt their trade as studio apprentices. Latterly, a foundation year, followed by a Fine Arts course, would have offered a technical grounding: life drawing, three-dimensional modelling, colour theory, etching, lithography, silk screen and so on. Actually, some of these skills have not been taught in art colleges for quite a while, so perhaps the gap between the trained and the self-taught has narrowed. (Judging by Damien Hirst’s 2009 show of paintings, narrowed to nothing.) In the end, in art as in poetry, the real formation is a subterranean, though not always imperceptible, weave of influence and affinity, even of aversion, and can never be understood by listing teachers and institutions.

After the age of 14, I’ve been more or less on my own as far as art goes, though I took the opportunity to attend free life drawing classes and an etching course at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. Nothing I did there was of any merit, except perhaps a couple of etchings, but it left me with an unrequited love of the medium. (Working with pen and brush in Indian ink or Chinese stick ink, I’m often thinking drypoint and aquatint.)

During the Covid-19 lockdown, perhaps like many others fatigued by a slew of words on the TV and other media, painting somehow felt easier than writing. Then, almost for the first time, I began making images to accompany poems, which meant overcoming a (perhaps unreasonable) distaste for any marriage between the arts. Even with the tremendous work of Blake, I’ve found myself liking one form rather than the other, his Songs of Innocence and Experience always more than his accompanying illustrations, and vice versa for the Prophetic Books. With David Jones I revere the art work more than the poems; with Henri Michaux I admire both equally, but I’m not sure either of them ever brought image and poem together (though Jones mentions that intention with In Parenthesis.)

In my forthcoming pamphlet, The Years, in which the two poems above are included with accompanying images, I’ve tried to make neither form, poem or picture, subserve the other. As I say in the foreword, I wanted word and image to converse, but for each to retain its autonomy.