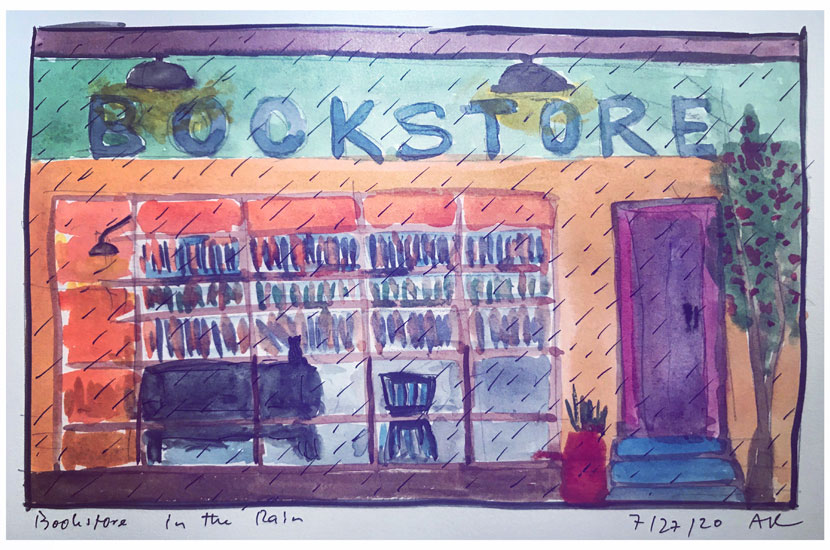

‘Bookstore In The Rain’ by Amitava Kumar

Coming Out of Lockdown: Literature, Life and Leaving the Centre

Kirsty Gunn

A year or so ago, I invited the Scottish writer Duncan McLean to come down from the Isle of Orkney where he lives to Dundee where I was hosting a series of literary events we called ‘Writers Read.’

This was a monthly get-together of students, teachers and anyone who was interested in reading and publishing, held in a convivial cafe where the espresso machine blasted every few minutes and the door onto the street would be opening and closing as people came in and out with their coffees, or settled down in one of the booths or at a table. The atmosphere was terrific; the cafe filled with poets and writers of all stripes, young and old, a combination of friends and newcomers, some published, some not … When our actual readings began, things quietened a little – though the machine still rang out, though less often, the door still banged – but the atmosphere remained informal. Charged with seriousness – with attention, with interest, with excitement – but informal. Sometimes we had a microphone (it didn’t work that well; Jamie, who runs Tonic which is the name of the cafe, had one on hand for visiting singers or quiz nights), often not. We would sit on bar stools in a corner of the room, and writers would read from their work. Then we talked about it, people asked questions, the writer read some more… Conversations, themes would develop. Afterwards, there might be a book signing , or there’d be news of a further event or publication, but it was the discussion that kept everyone at Tonic well after the reading had finished. Something had started; people wanted more of it. The visiting writer would hang around, have a coffee or a glass of wine…carry on talking until, in time, I would thank Jamie and everyone at Tonic and would usher our visitor out the door. As I say again: these evenings were informal. The writer was part of an event; this person was not a rock star or a guru or ‘famous’ but an artist and intellectual, a creative thoughtful individual who was happy to read and talk about writing with others who were also interested. *

Duncan was one in a long and wonderfully varied programme – of novelists, poets, nature writers, songwriters, non-fiction writers and more – and it had taken him a while to get to us. I’d asked him to be a guest at ‘Writers Read’ some time before – I’ve long admired Duncan’s work, right back from when he first published his extraordinary vivid and shockingly funny and dark collection of stories Bucket of Tongues back in the nineties, and had invited him to Dundee on another earlier occasion to read with his friend Alan Warner, whose work I also love, and who has known Duncan for a long time. That event had resulted in both writers first going out and living and then creating, overnight, a short story from that experience which they then read aloud the next morning, minutes after having finished it. I can’t remember when I laughed so much at a literary reading. Duncan is a tall man, with great presence, and is also a playwright and translator -so he has a fine ear for the sound of a word, for the second by second delivery of a sentence. Anyway, all of this is to say that after that first visit it had taken a number of years for us to get him to come back to Dundee for his second because life is busy, but more than that, life, for Duncan, is lived on an island that is relatively hard to get to, and hard to leave. Though only a ferry’s ride from the mainland nevertheless Orkney lies off the northernmost part of the British Isles and the ferry docks in the remote and, locals will admit, most closed off county in Scotland, Caithness; it takes a fair amount of time to get to and from both places. So, there are trains but they are not frequent; flights are not scheduled often and are expensive. The North Sea can be rough; ferry crossings, last minute, get cancelled. Dundee is by no means a literary ‘centre’ (though I have to say, at our ‘Writers Read’ sessions we were working on that) but Duncan McLean is also nowhere near Dundee.

This is precisely what I had asked Duncan to come and talk to us about. For a while now, he has been writing and thinking about what it is to have a literary life that is at a distance from the so-called literary centres of the world – the New Yorks and Londons, for versions of these places exist, too, in Edinburgh and Calcutta and Wellington and Toronto and lots of other places; ‘hubs’ I may also call them in this essay. He has his own Orkney-based publishing venture and magazine, Abersee, that encourages a local literary culture, yet one that is also outward facing, and internationalist: referencing translation; international politics and imperialism. ‘Think global, act local’ is Duncan’s motto, overturning the usual tendency to globalise local culture ( as evidenced in trends in mainstream publishing over the last thirty years or so**) by maintaining a steadfastly local presence and celebration of language and sensibility in the magazines and pamphlets he publishes which bring world issues and international preoccupations to Orkney. And does he want to do more than this? Increase his remit to set Orkney in a global context? Does he want to build Abersee, in time, towards becoming a profit making business that he can sell on to a larger house that’s decided it wants to acquire something of the funky presence of an island-based literature to add grit and ‘inclusivity’, burnished by the presence of a writer who was once hailed by the New Yorker as one of Robin Robertson’s, then literary publisher at Secker and Warburg, ‘Scottish beats’, along with Irvine Welsh and James Kelman, and photographed by Irving Penn?

The answer to these questions is a massive rumbling laugh. Duncan could not be less interested. He is doing what he is doing because he is engaged by the local – as expressed through language and poetics – and one of the many things we talked about in that ‘Writers Read’ was his work around the New Zealand short story writer Frank Sargeson, who had published in the thirties and forties a kind of New Zealand ‘demotic’ fiction. Though writers such as EM Forster had praised Sargeson’s work, and while he was revered in France and Europe, London, the English Speaking Centre, had been unable to hear the particular New Zealand rural idiom of his voice. Duncan has written about all this, in the LRB actually – a terrific example of his thinking globally, and acting local right there – and continues to maintain a lively interest in New Zealand literature post-Mansfield, seeing in its regional priorities and sounding of voice something akin to what he has been part of as a member of the so-called Scottish renaissance, that time when working class idiolect and dialect from Glasgow and the outlying country found a place in the pages of internationally published fiction. All this, the founding of an individual’s language, the relation of islands to the Centre, whether the North and South Islands of New Zealand or the Isle of Orkney, the quality of what Elizabeth Bowen described in Katherine Mansfield work as ‘speaking’ness’… it means Duncan and I had a lot to discuss. ***

‘Beach Reading’ by Amitava Kumar

I am inclined at this point to bring into this essay another Scottish publisher and writer who is working quietly away, far from the hub – also based on an island, I realise, though living on an island is by no means a prerequisite, in this essay, for being defined as one removed from the Centre! – to form a literary centre that is defined as such by a person of culture, of literature – not of business and finance. Kenny Taylor, who lives and works on the Black Isle, in Easter Ross-shire, is the editor of NorthWords Now magazine, a free literary paper circulated twice a year throughout the north of Scotland – though also available, in certain places, as far south as Edinburgh and Glasgow. Since taking over the role from the poet and teacher Chris Powici, Kenny – a nature writer and naturalist who has previously worked for National Geographic and the BBC, and published widely on environmental issues and Scottish wildlife – has worked vigorously to increase the remit of NorthWords Now – to extend its gaze further and further North, as Scotland as a country aligns herself increasingly with Scandanavian culture, and works to build networks that might span the Arctic circle all the way into northern China. This is a new kind of ‘trade route’, Kenny suggested, at a literary conference in another relatively remote place, Arbroath****- though not ‘remote’ at all of course, if you live and work near there and are not locked up in some hub. There, at Hospitalfield House, a group of international writers and scholars from New York, Oxford and Paris amongst other places, had gathered to talk about the essay form; discussions that would provide the basis of a collection of essays, Imagined Spaces, itself a further unlocking of dominant centrist paradigms. ***** Kenny had been suggesting, not necessarily much interested in economics himself, or in the fiscal sense of opening up a train route across the top of the globe, that the new network she’d been outlining might have impact in literary terms. He is already translating and publishing the work of little-known Norwegian poet Olav Hauge in the magazine and other places, while encouraging that kind of internationalist literary activity in the submissions of his writers – who include the poet Lesley Harrison, whose collection Blue Pearl is published by New Directions and who carries Duncan MacLean’s ‘global’ thinking in her ‘acting local’ dna.

Altogether then, the activities of NorthWords Now, along with Duncan’s Abersee in Orkney -a kind of publishing and thinking that is free of metropolitan priorities and is open to new geographies and imaginative principles -this feels more and more relevant and interesting to me in a way that mainstream global publishing is not. Relevant because… Thoughtful. Of a modest scale, perhaps, and very much operating at grass roots level, but principled and imaginative; an activist-based working model with an agenda that is truly intellectually and aesthetically driven, and at far remove from the spread sheets and profit margins of the multinationals, leaping as they are, upon all kinds of newsworthy issues, to be ‘Now’ and ‘Exciting’ and ‘Contemporary’ while remaining locked down in the conservative, financially defined, profit-motivated Centre.

In a recent discussion with a publisher who asks to be kept nameless – someone with a highly respected background and profile in the literary world and who has seen a great number of authors through his offices gain international prestige and acclaim but who has always followed his own taste and never published anyone for any other reasons – I was told that literary publishing is now ‘pretty much dead’. The big conglomerates keep on people like him, he said, to make them feel that they are still publishing ‘real’ literature; that they might capture the odd Nobel Prize winner or catch a new latest thing, ride the wave of the zeitgeist, while adding together the figures on the mainstream list so it all tallies up. Another publisher I know calls this sort of activity ‘fig leaf publishing’ – where a distinguished editor is brought in to polish company prestige and create a bespoke list so that the giants roaming around at the top of the top ten bestseller lists have at their back something artisanal and intellectual that feels ‘highbrow’, was the word he used. ******This seems to be where and what the Centre is about: A golden triangle of the big multinationals set firmly in the midst of their world cities reaching out to further centres and hubs around the world that seem to reflect its values in a range of book festivals, trade fairs and prizegivings. All exuding sophistication, worldliness and prestige through astute financial management, big international visibility and vast amounts of ‘cultural capital’ and making us believe, somehow, that this is what literary life is all about.

How moribund it appears now, this enormously scaled business; how monotonous, after the other merry conversations about language and place and identity happening in a rangeof individual centres of thought and culture that are nowhere near some hub. And, I think now,how realistically and truthfully ‘inclusive’ is the kind of thinking going on in these far-flung places – set against the mainstream politics of our mainstream age that is played out upon the bright lit stage of the metropolis, back lit by an authorised, privatised concept of ‘culture’.

And talking of stages, and by way of concluding this piece of mine – that I can see, by the notes that appear at the end of it, and by the many pages that have accumulated in my writing of it that have not been accommodated here and could go on for more page numbers than I have available here – let me return to that image of the writer talking with his readers in a cafe in the rain, the door flapping intermittently to let in those who’d come in to escape the weather and found themselves staying, to listen on. For in comparison to that jolly afternoon, a final example comes to mind that may summarise, perhaps, what I’ve been trying to get at here; an anecdote to describe the way the very idea of literature – or LITERATURE!, for the word seems to come in shout capitals these days – has become, over the past thirty years or so, more and morecontrolled and enclosed by lockdown centrist thinking.I was in the ‘Green Room’ of an INTERNATIONAL LITERARY FESTIVAL, before my scheduled EVENT that afternoon, and – just as is suggested by the terms that were and are in use at these kinds of affairs, the language of the entertainment business employed with no sense of irony –waitingto ‘go on’ . I was in conversation with a writer friend. This was no discussion at Tonic, though. We were inhabiting a kind of Hollywood, so it now seems to me – with its hosts of young people toting clipboards, and sound engineering teams and lighting specialists on hand to ‘mic’ us up!’ and ‘do the sound check’ and run ‘spots’ teststo make sure one can read and not be blinded by the strength of the theatrical lighting. There was a restless anticipatory atmosphere around the marquees and tents, the roped off VIP areas and Media offices. A BIG NAME AUTHOR was in the vicinity, we’d been told, and, though no one could see him, like a rock star he’d been ‘flown in’ and was there, somehow in our midst. I remember having lost track of time, suggesting to the author I was talking with – no stranger herself to the celebrity culture, a fabulous writer who also knows a thing or two about ‘working a room’ and holds large throngs of people spellbound in events that she still calls ‘Readings’ – that we might pop in to another reading I’d justrealised was on at the same time, our author lanyards allowing us open access while we were visitors at the festival, to all events. She was aghast. ‘You can’t interrupt the performance that way’, she said, with no sense of irony or side in her elision of literary activity and entertainment. No matter that the author was someone we both admired, whose work we had been following over the years and had been engaged by… The show had started, the doors were closed.

So the lockdown, the securing of literary value to the market place, is complete. From reader to ‘readership’, from the individual who thinks and reads and makes judgment about what she reads, writes about it even, to ‘customer’ to ‘audience’ to ‘the market’… I seem to have missed exactly when I became aware of not wanting to be stuck in that place, but now, out and about, breathing fresh air I realise I don’t want to be troubled again by the implications of what my fellow author said to me that day; I want to put it behind me. ‘We could just slip in’ I’d said, ‘and sit at the back. After all it’s XX. He won’t mind. He knows how much we love his books.’ She turned to me then, and was firm, set as she was in her place in this new literary landscape of ours, a bright, bright star. A writer who knows well how it works, publicity, marketing. How everything is figured out for benefit, weighed and valued, culture as commodity and how behaviour, predilections, taste – all follow suit . ‘You can’t just SLIP IN’ she said to me, and, to my regret that afternoon, I took her advice, as though what she’d said was the only reality, as though it were somehow true. ‘It’ s too late’ she said. ‘It’s started. You’ve missed it.’ For it’s only now, coming out of the tent for some air, I’ve realised how, in the manner of all closed performances, an event – literary or otherwise, historical or current – can only indicate one version of what is going on. And yes, the door is shut on that spectacle, the programme fixed. But look, come with me onto the grass. Something else is starting. Let’s see what’s happening over here…

Notes:

* The ‘Writers Read’ series was something I initiated while directing a writing programme at the University of Dundee. It developed out of an earlier iteration along similar lines – that is, the creation of an informal space in which to bring all kinds of writers to the city, from the very well known (including real live rock stars and actors, Booker prize winners and their publishers) to the reclusive and near invisible from whom we also learned an enormous amount about resilence and patience and writing as intellectual activity. It was a terrifically successful and interesting programme – starting at the DCA, which was an exciting and unique contemporary gallery at the time, as the Literary Salon Series, and continuing, after a change of management and ethos there at groovy Tonic, where Jamie and Dave and Melanie and the team gave over their cafe to our deliberations.

** See Amit Chaudhuri’s writings and talks on this subject for a gnarly and comprehensive survey of the landscape which has informed his establishing of the Literary Activism Centre through institutions in England and India.

*** I have written a great deal about Katherine Mansfield and her relationship to the Centre – most recently in Katherine Mansfield Studies, ‘On Being Chased By A Bull’, EUP, and Duncan MacLean and I have ongoing conversations about NZ literature and the demotic and contemporary Scottish culture which are regenerative and inspiring.

**** Kenny Taylor spoke about the idea of the north at Hospitalfield House as part of a conference about essays and uncertainty, and is published, in conversation with Duncan MacLean, in the forthcoming volume ‘Imagined Spaces’ that came about as a result of that conference.

***** ‘Imagined Spaces’ is published by The Voyage Out Press, a small publishing company the writer and publishing historian Gail Low and I have established to explore ideas of hesitancy, uncertainty and tact in literature and celebrate intellectual collaboration and generosity.

****** A whole new essay to be written here! On the relation of so-called ‘high’ art and ‘serious’ literature to metropolitan publishing; the creation of a ‘consumer culture’ disguised as non-transferable ‘value’.

Kirsty Gunn writes fiction and essays and directs, with Gail Low, The Voyage Out Press, a publication exploring ideas of uncertainty, risk and the role of the imagination in writing and education.

Amitava Kumar is a novelist, non-fiction writer, and artist. The pictures above comprise his response to Kirsty Gunn’s essay.