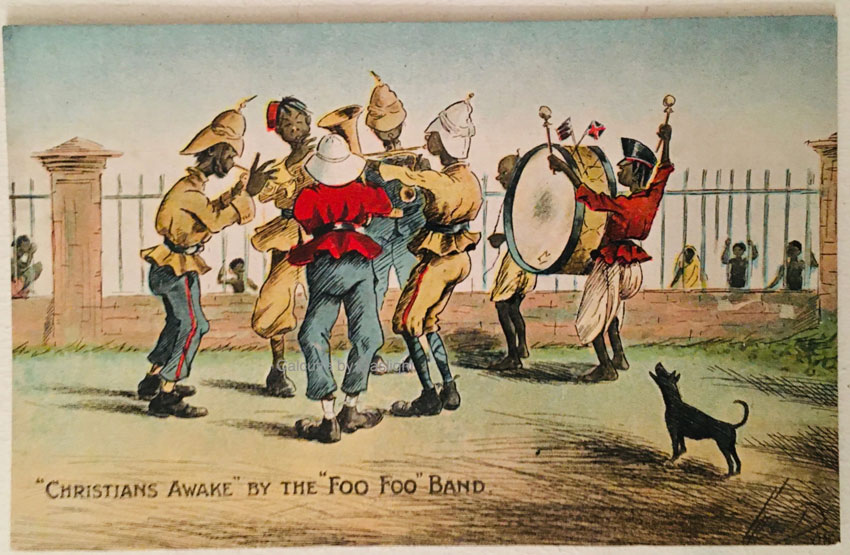

Christmas in Calcutta: a postcard by George Darby.

‘English New Year’ and other poems

Iswar Gupta

Editor’s note: The English translations below, of three poems by the 19th-century Bengali poet Iswar Gupta, are part of an ongoing project. The impetus for it occurred after Arvind Krishna Mehrotra read Rosinka Chaudhuri’s chapter on Gupta in her study of 19th-century Bengali poetry, The Literary Thing. The poems below are probably the first English translations of the Bengali poet.

‘Samay’ (‘Time’) and ‘Chhadmabeshi Missionary’ (‘Missionary in Disguise’) were translated last year by Rosinka Chaudhuri and Mehrotra from the excerpts selected by the writer Kamal Kumar Majumdar in Chhara o Chhobi (his selection of Gupta’s verse). The idea of attempting to translate the untranslatable ‘Ingrāji Nababarsha’ (‘English New Year’) came to me as 2020 ended. Arvind and Rosinka responded to the suggestion with generosity. The poem has been critically annotated because of the inventiveness of its language (which includes many English words), its provocative use of onomatopoeia, and the richness of its references.

Iswar Gupta: A Brief Introduction

The most famous poet in Bengal in the years preceding the great rebellion, Iswarchandra Gupta started his career at the newspaper he set up (the Sambād Prabhākar) as a nineteen-year old in colonial Calcutta in 1831, the year that saw the death of Derozio in the same city. His predecessors in this field, if they can be called that, included not just Derozio in the English language, but, in his own, the creator of the tappā in semi-classical Hindustani mode Ramnidhi Gupta, Ramprasad Sen, whose devotional songs to Kali are sung even today, and the pre-eminent poet of the eighteenth century, Bharatchandra Ray.

Iswar Gupta’s literary achievements, however, were rooted in a modern urban idiom unknown to those who lived before him. Traditionally a member of one of the intermediate upper castes, Iswar Gupta belonged to a class of professionals created in Calcutta by the exigencies of colonialism, whose life story could only have been thrown up by the paradoxical modernities of the time. For, while we may claim for him the distinction of being the first modern poet in the Bengali language, he was also, at the same time, a well-known part-time kabiāl (singer-songwriter), writing the lyrics for a group located at Bagbazaar, in an occupation known as the bāndhandār or wordsmith.

Jorasanko, home to the Tagore family, was where the famous kabiāl groups were based and where Iswar Gupta came as a child. Born in 1811, he moved to Calcutta after his father died, and standard biographies take care to mention that he was never formally educated, emphasising instead his natural abilities in versification and song-writing, his keen memory and sharp intellect. He was known to have composed poems and songs even as a child. (Bankimchandra Chatterjee says, in this context, quoting Pope: ‘He lisped in numbers, for the numbers came’.) The next noteworthy biographical fact has to do with his friendship with the Pathuriaghata Tagores, specifically Jogendramohan Tagore, who helped him to establish the Sambad Prabhakar in 1831 when he was only nineteen. From this date till his death in 1859 at the untimely age of forty seven, Iswar Gupta flourished as the pre-eminent poet and editor of Calcutta, publishing poetry regularly in the columns of his newspaper, composing songs for a kabiāl group of Bagbazaar, collecting the songs and poems of the preceding era to create an unprecedented archive, as well as commenting, in verse and prose, on most aspects of the new life of the Bengali people in the mid-nineteenth century.

By the time Bankimchandra wrote an introduction to a collection of his poetry in 1885, Iswar Gupta was no longer remembered as he should have been. The year before he died, a crucial juncture in the formulation of a national modernity in the Bengali language, Rangalal Bandopadhyay had published Padmini Upakhyan prefaced with a literary manifesto deeply committed to English poetic theory and practice, Pearychand Mittra published the first Bengali novel in book form, Alāler ghare dulāl, and Madhusudan Datta wrote the first modern Bengali play, śarmisthā nātak.

Bankimchandra’s famous allusion to Iswar Gupta as the last ‘authentic’ Bengali poet [khanti Bangali kabi] in his summation has led to a fundamental misreading of this poet ever since. Looking at the language, idiom, style and substance of the poem you are about to read, recording the English New Year of 1852, it is obvious that this ‘painter of modern life’ met every criteria laid down by Baudelaire in his essay of the same name. If by ‘modernity’ we ‘mean the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable’, then this is, rather, our first poet of Indian modernity.

Rosinka Chaudhuri

Missionary in Disguise

In Hendo Woods, roams a fat tiger with red cheeks. I only have to hear the name and fear grips my heart. Grabbing dharma by the throat, he rips out its jugular with his claws.

As a boy, I’d heard of boy-catchers,but this one I’ve seen with my own eyes.How do I even say it? The boy-catcher missionarypounces on young boys. Afterwards, he smacks his lips.

*Hendo A locality in north Calcutta with a number of schools and colleges established in the nineteenth century.

Time

Feeds on emptiness

Spends its days in emptiness

And doesn’t once look back

It was Pisces, returns as Taurus

It lowers its head, it stands on your chest

It eats grass, brings you up as cud

(Translated by Rosinka Chaudhuri and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra)

ENGLISH NEW YEARi

1852

(Translated by Amit and Rosinka Chaudhuri, and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra)

iThe title of the original is Ingrāji Nababarsha. The lines that follow, though they comprise most of the poem, are taken from the excerpt made by the novelist Bankimchandra Chatterjee (1838-94) from the complete poem. The poem is written in rhyming couplets in the mishra kalabritta payar, a metre with eight beats in the first line and six in the second, common to devotional panchalis about gods and goddesses. To see it used here to bring to life a new profane, aspirational world is a cause for shock and delight.

iiThe original says chrishtamat: literally, ‘according to Christian belief’.

iiiIn the original, shweta nar: literally, ‘white man’. This term points to the many difficulties of translating Gupta. There is no such generic term (‘white man’) in Bengali – the closest one carrying similar connotations is saheb, used both generically and also ironically, and which occurs frequently in this poem. Shweta nar, in this line, is purely descriptive, estranging, and ironical.

ivWomen.

vPhonetic incorporation of ‘fresh’, one of Gupta’s many jaunty incorporation of English words in the poem.

vi‘Feathery flourish’.

vii‘Dress’.

viii‘Slipper’.

ixGupta is playing, in this line, with the fact that the Bengali pronunciation of the English word ‘rose’ and the Bengali word for ‘every day’ are homonyms.

xAmbrosial nectar.

xiThe god of love.

xii‘Ribbons’.

xiiOnomatopoeia related to the sound of water.

xiv‘Buggy’.

xvKhana: Urdu for ‘food’. Tebil: ‘table’.

xvi‘Sherry’.

xvii‘Gown’.

xviii‘Very best’, sherry taste’, ‘merry rest’: Gupta’s characteristically brazen and mocking agglomerations of English words, in tight clusters that observe, at the same time, the metre of the payar.

xixPoetic language in Bengali, as in Sanskrit, did employ onomatopoeia whenever needed, and there were recognized words denoting sound (although never used in quick succession and in such quantity, perhaps). These are new, though, created by Gupta in response to the strange world he’s describing, and are meant to suggest the sound of heels and footwear as people arrive at their tables. Rosinka Chaudhuri, in her chapter on Gupta in The Literary Thing, calls them ‘sound images’, and compares them to a ‘live playback recording of the changing shape of the everyday on New Year’s Day, 1852’.

xxThese suggest chewing, probably. The onomatopoeia, as is clear, creates the line in this section, and is as worth pausing over for its evocation and formal shape as any ‘meaningful’ line of poetry is.

xxiSlurping sounds; probably of soup being eaten.

xxiiThis and the previous line most probably have to do with the noise of cutlery, and with further food-related sounds. Tosh tosh is recognized onomatopoeia, usually to do with the dripping of syrup, water, or tears. Ghash is the sound for cleaning or scraping.

xxiii‘Hip hip hurray’; ‘whole class’.

xxiv‘Dear Madam, you take this glass.’

xxvGuru guru is onomatopoeia traditionally used in Bengali for thunder; goom goom suggests a bass noise. The English orchestra has a deep thunderous sound to Gupta’s ear.

xxviThe beat.

xxvii‘Chop’ is a word that at some point entered the Bengali language from English, but generally denotes, unlike in the English language, anything that is crumbed and fried.

xxviii‘Cake’.

xxix‘Take, take, take’.

xxx‘Sherry, cherry, beer, brandy’.

xxxiAloophish is a portmanteau combination of aloo and phish – ‘potato’ and ‘fish’.

xxxiiWhites or fair-skinned people. A transition has been made here: the poem is now also needling constituencies like the renegades of Young Bengal, a group of Bengal is from the 1830s who wished to cast aside religious taboo by eating beef and pork, and who also mingled freely with Europeans.

xxxiii‘Don’t care for “Hinduness”, damn damn damn’.

xxxiv‘Name’.

xxxvThere’s complicated punning in this bit of the line. Gupta’s ‘mish’ (for ‘miss’, or the Englishwoman) is a near-homonym for the Bengali word for mixing. It also means’ black’. This introduces the matter of mixing – or not – with dark-skinned people.

xxxvi‘Fame’.

xxxviiMemsahibs – the ‘native’ ones.

xxxviii‘Black native lady, shame shame shame’.

xxxivVermilion powder.

x1Some of the early 19th-century Bengali concern with the position of women and religious superstition is being woven in here. What’s remarkable about the the poem is the number of contemporary registers and new realities it can accommodate while remaining focussed on its subject, and on its approach, mockery.

x1iPlaying on the Bengali phonetic transcription of ‘merry’ and ‘Mary’, leaving the Bengali reader guessing – as with much of the poem’s English imports as well as its onomatopoeia – about which is which, and what’s what.

x1ii‘Very good boy’

x1iiiThis is an extraordinary devotional moment that has been slipped into the poem, expressing the sort of transgressive spiritual inclusiveness that informed bhakti, and would later, in that century, be revisited by Ramakrishna. This is also a note sounded by the kaviāls or oral poet-performers of early 19th-century Calcutta, among whom Gupta counted himself: these two lines comprises a kaviāl-like utterance in print.

x1ivAccording to Rosinka Chaudhuri, this is probably a corruption of ‘Duff’, and a reference to the Scottish missionary Alexander Duff (1806-78), with whom conversions in Calcutta are associated. So ‘Duff’s tub’ would refer to baptism.

x1v‘Go to hell’.