End-of-the-Year Counter-Question

Editor’s note: I sent the note below to a few people, and their responses appear further down.

We live in a time when the main cultural events of the year are marked in advance on the calendar: like the Booker Prize ceremony when it comes to the novel. How can a prize-giving ceremony be that year’s most notable literary occurrence; how can we know that the most notable occurrence will take on, unfailingly, a particular incarnation? Why do the Books of the Year lists that appear in December have the inevitability of a plot development that we feel at once cheated without and bored by?

The pre-assignation of a proper place and time to the ‘major’ cultural event, and our subsequent unconcern with what such a thing might be once those dates have passed, is part of the (I hesitate to use the word, but can find no other) neo-liberal legacy of the last three decades. In Britain, it belongs to a version of culture approved of by Thatcher and Blair. In other countries, it’s had the blessing of related dispensations. Whatever the hegemonies in 1924 or 1975 (to take two years at random) in whichever country, there was, at the time, no reliable prior knowledge of what a major cultural event comprised. The idea was a work in progress.

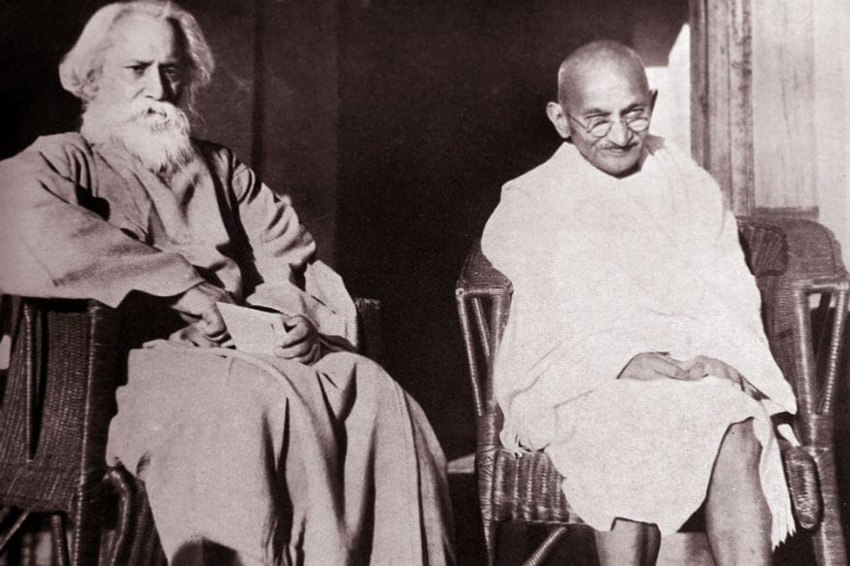

From an essay by the Bangladeshi critic Anisuzzaman, translated by Sukanta Chaudhuri, we learn the following: ‘Rabindranath’s close associate W.W. Pearson tells an anecdote about Tagore and Gandhi. He asked both of them the same two questions: what did they consider their greatest virtue and greatest vice? Gandhi returned an evasive answer. Tagore’s was both pungent and profound: to both questions, he replied, “Inconsistency.”’

In the spirit of Pearson’s question and Tagore’s response – that is, in acknowledgement of a world lacking in reliability and consistency – I’d like to ask what you think of as a notable cultural event from this year, or even the previous one, or from any year you choose.

Responses

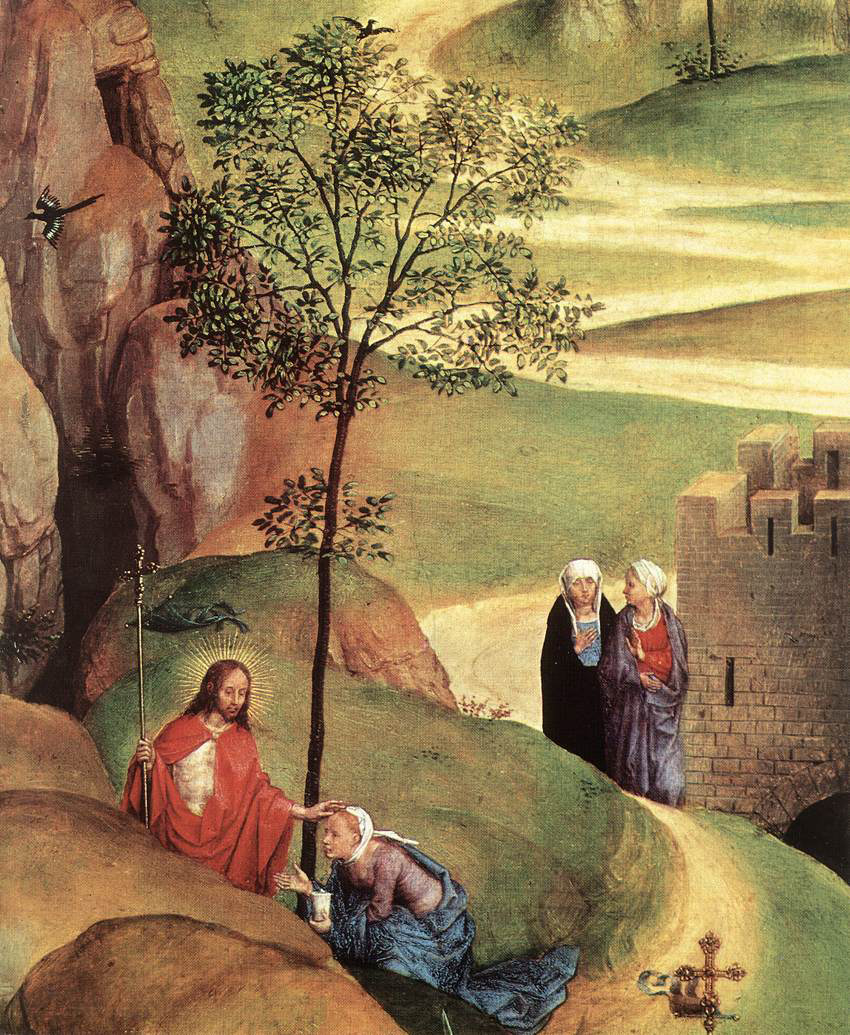

Advent and Triumph of Christ by Hans Memling (c.1433-94)

Charles Bernstein

Eventuality

One of my worst habits of mind is to assume that a work of poetry deemed ‘notable’ by the leading cultural organs must not be any good. After all, just being singled out for praise by one of these publications or prizes doesn’t guarantee humdrummery; mistakes can be made. Sometimes I’ve been one. But it’s fair to say that very few of the poets I most care about have been deemed ‘notable’ outside the inner sanctum of dedicated readers focussed on pataquerical poetry.

I won’t provide a year-end roundup of this year’s most notable poetry-related books, but just say there were plenty and they were plenty ignored. But notability does not make an event. Events in poetry are more likely to ripple underwater than be a splash, though I aspire to both.

Event is one of those words long mangled in the threshing machines of philosophical analysis. You know: the only true event is a non-event. Or you don’t know what an event is until you see it and when you do you are likely to repress it (or it will repress you).

Or, as we use to say, It’s not an event, man, it’s a happening, I mean it’s happening man, can you dig? – Don’t bring me down with all this event claptrap.

Then there are the religious connotations. But like the saying goes – messiahs keep coming and going but waiting’s not going anywhere.

Or am I confusing event with advent?

I guess if I really wanted to be theological, I’d say my concern is not the event but the eventual. That sounds good, but God knows what it means. Or maybe Emerson might – only a moving toward, never a grand finale. To Tagore’s marvellous paradox that ‘inconsistency’ is both the greatest vice and virtue, I’d add inconstancy. I just mean that sometimes in the spluttering of rethinking and reconsidering and recalculating, there is the possibility of an ingenuity necessary for both the event and the eventual.

I seem to be saying that for something to be an event it can’t be named and, especially, can’t be named notable. But that can’t be right. I’m no gnostic. I acknowledge and celebrate the poets I admire, as I do Paul Celan, whose one hundredth birthday is now upon us. If any poet’s work is an eventuality rather than event, it’s Celan.

Acknowledgement and celebration allow eventualities to become events (and the other way around). Right now it starts here, in conversation, at Literary Activism.

*

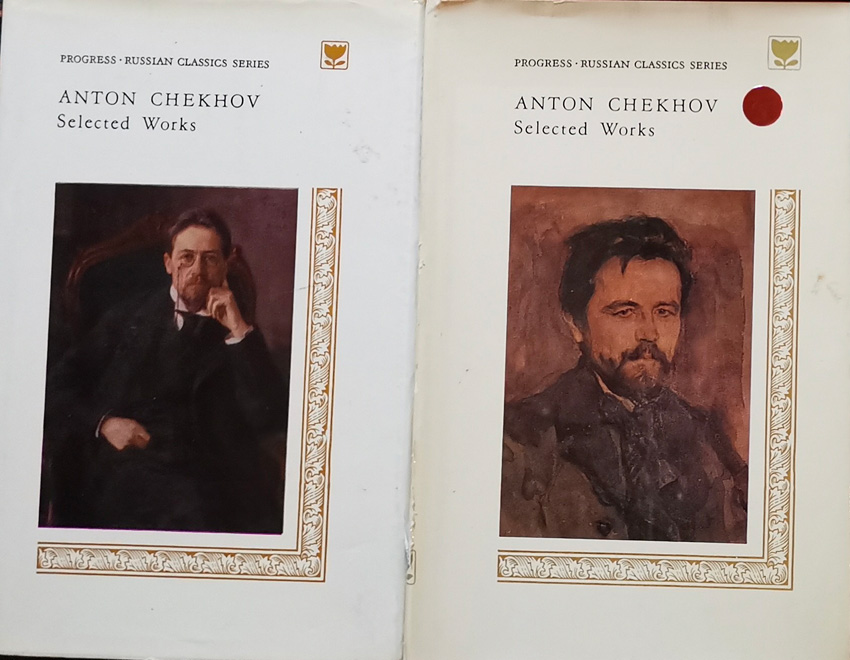

From Pankaj Mishra’s collection

Pankaj Mishra

An Annual Commitment

Is there an experience of reading that approximates, in its involuntary recall of forgotten landscapes, Marcel’s encounter with a madeleine? Early in the lockdown this year, I became aware of a new translation of Chekhov’s stories by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Oh, good, I told myself. Re-reading Chekhov has been an annual commitment, observed more or less scrupulously for three decades. The translations have varied. Depending on where I was, in India or the UK, I would reach for Ronald Hingley or Constance Garnett. A few years ago, I downloaded a volume of longer stories translated by Pevear and Volokhonsky, but found them oddly difficult to read on Kindle.

The new translation was due to be published a few months earlier in the US than in the UK. I decided I couldn’t wait, and ordered online the American edition. At some point, waiting for the volume to make its way across the Atlantic, I grew restless, and started to look on the internet for the editions which, published in Moscow in the early 1980s, I had bought at a mobile bookshop that went around small towns in Uttar Pradesh.

A rare books dealer in the United States offered these pre-Perestroika artefacts at several times their original price. In a reckless mood, most likely borne out of the constrictions and uncertainties of the lockdown, I paid the exorbitant amount.

The volumes took several weeks to arrive. But the trap doors of memory sprang as soon as I opened them. There was the typographical arrangement imprinted somewhere on my brain by several perusals, and the familiar smell of Soviet paper that had survived a long exile in the free world.

Something more from what often seems to be me an unshareable past was recovered when I started to read. I began with Chekhov’s longest story, ‘My Life’, which features a provincial railway station. I had read the story for the first time while travelling on a steam-engined train that used to run on a branch line from Benares to Allahabad. At some point, I remember, I looked up from the page to find Chekhov’s railway station outside my window.

For years afterwards, the same configuration of unroofed platform and corrugated-iron shed in the middle of sugarcane fields emerged in my mind when I reread the story, together with the sighs of a reposing steam engine, and an incongruous image of shattered kulhads, clay tea-bowls, on the ground.

Over later re-readings of the story, and after broader travels, other train stations supplanted it. Meanwhile, the branch rail line was closed, and steam engines sold as scrap metal. Now as I re-read Chekhov in London on Soviet-made pages after nearly three decades, a simple landscape that had faded into darkness abruptly rose before my eyes, and, with it, powerfully and exhilaratingly, so much else that had passed out of memory.

*

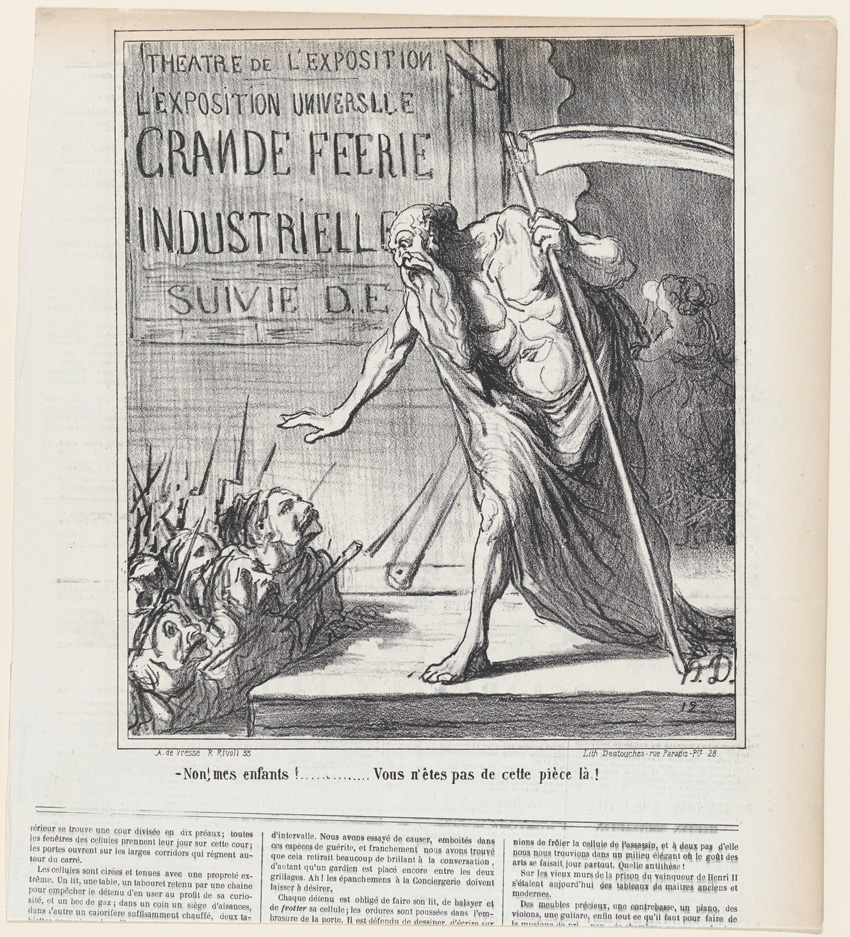

‘No my children… you are not part of this play here!’, from ‘News of the day,’ published in Le Charivari, March 8, 1867. Picture by Honoré Daumier in the MOMA collection.

Marco Roth

‘Quar Hovel’

Sometime, during the third week of the spring lockdown in New York City, on or about April 1st, I was watching a video, live recorded on an iPhone and uploaded to YouTube. The video was made by a performance artist and actress, a friend. Her breakthrough solo show, the culmination of three years of smaller shows in various tiny theatres and avant-garde ‘performance spaces’, had been cancelled by the virus outbreak. Already living hand-to-mouth, she’d adopted the expedient of soliciting Venmo donations for her work. In this video, which she’d named ‘Quar Hovel’, she plays a composite character, part medieval German peasant woman during the bubonic plague, part the yoga, fitness, life-coach, and online ‘guru’ type, usually young, peppy, and female, who’s popped up in recent years promising health, self-actualization, and, of course, a source of ‘entrepreneurial’ income liberated from the traditional ‘gatekeepers’ of one’s chosen field.

The significance for me of this particular performance had less to do with my friend’s comic character, although the persona’s composite anachronisms contributed to the heightened absurdity of the situation we found ourselves in. Rather it became clear that she’d managed to channel her own crisis to stage the most effective condensed critique of the conditions of ‘performance’ and the fate of cultural events that I’d seen in the nascent pandemic era. Just as she had tried to engage her audience in her live stage performances, to improvise off the lines they might feed her, or the feeling, or energy she received from a live room. Her particular style of clowning had indeed depended on these connections through the fourth wall, and one of her great talents was in her ability to read a room, as the cliché has it, both gaining a psychic energy and insight from her audience, playing expertly on their anxieties and desires, and returning all of it to them doubled, transformed. Here she had only herself to draw upon, to dance with, and the viewer could feel it. She had the great talent and art of being able to transform her body, in seconds, in the way that only the best actors do, to convey a character also in a drop of shoulder or walk, things that were only really discernible in three dimensions. That absence of that dimension hurt.

Faced with nothing beyond the tiny screen of her phone, she allowed the loss of her audience to enter her improvisations. The loss, in fact, became the theme. Was there anyone really out there? The guru mask cracked and she let us see the character’s loneliness, which might have also been her loneliness and was certainly our loneliness. Even though the video was overlaid with ‘real time’ emoji responses and texted comments from her friends, she couldn’t see them, let alone respond to them. The updated commedia dell’arte masks she made, toyed with, and tried to sell to the invisible audience as ‘plague masks’ had the effect of rendering all faces, as they appeared flattened by our screens, into masks. The clown show that attempted to bridge our shared isolation became about her alienation, our social distance.

What she performed, on the edge of uncontrolled hilarity, wasn’t so much an adjustment or capitulation to the brave new world of the ‘online only’ event that we’d been urged to inhabit – for our safety and the safety of others, of course – as an act of resistance to it. Here was a protest and an act of mourning carried out in the idioms of the clown who knows only that the show must somehow go on.

Much about the conditions of our impoverishment and severing that the video put into play predated, in fact, the arrival of the virus and the lockdowns and shutterings. Almost all of our cultural experiences were already being mediated and sifted through digital technologies: a single line on Twitter could be more ‘impactful’ (one of the dreadful new words of the last few years) than the long-maturing work of a novel. Indeed the tweet might come to stand in for the novel in public debate about the novel’s value or worthiness. In a similar way, an Instagram or YouTube influencer or personality whose amateur productions my friend parodied in her video was, ‘in real life’, better compensated for their performances than my friend, who’d trained for years to act in live theatre, was for hers. Until the pandemic, it was still hard for many of us to credit the ontological or epistemic status of events that happened only ‘on the internet’: tweets, YouTube videos, Substack posts. How important, how real were these seemingly pseudo-events? When did a tweet become ‘news’? It made sense that capitalism, used to dealing with phantom commodity forms, would find ever more frontiers to monetize, and that some of these would be even more conducive to its penchant for abstraction, the removal of any material good from the exchange. But there were still those brief moments when we could be outside the system, devoted to the inefficiency of the concert, the mystery of the play, the expectation that what we were seeing was unrepeatable.

The pandemic, like the triumph of the twitter despots that preceded it, appeared to thoroughly reverse the orders of ‘reality’. Our physical existence, tenuous and threatened, was also barren. Culture happened, if it happened at all, in the screen world. The ‘nature’ of that world – wires, cables, microchips, software, etc. – was as opaque to most of us as the workings of the biochemical systems in our body to the non-specialist. Culture, that is to say the playful manifestations of the human mind, if it happened at all, if it had a theatre, was taking place between these two bodies whose workings are increasingly outside or beyond our abilities to readily cognize them.

*

Anti-CAA rally culminating near the Gandhi statue at the Mayo Road crossing, Calcutta, on 10th January 2020.

Amit Chaudhuri

In reply to my own question

As the year draws to a close, it occurs to me again what an extraordinary thing the mass protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India were. Of course, they began late last year, in December 2019, but I have asked others (and myself) to depart the ‘list of annual significances’ paradigm. Besides, if we can refer to a century as ‘long’ and investigate its leakage into a previous or succeeding era, we can surely do the same with years. Few years deserve more to be called ‘long’, its beginning and end impossible to pinpoint conventionally, than 2020, with its migrations homeward of workers, its devastating religious and ethnic conflagrations, its various hostilities to, and reassertions of, free speech, its Brexits, American elections, viruses, and face masks.

The CAA (in abeyance since April because of the pandemic) is itself not only a political programme but the latest in a series of strategies aimed at reforming (or deforming) India’s culture, in this case by indicating that Muslim refugees from neighbouring countries won’t qualify for the citizenship that will otherwise be granted to those of other religions. Similarly, the anti-CAA protests have been not just a political event on an unprecedented scale but a cultural one. Even jokes on posters – also because many of them were in Hindi – were evidence of the historical contexts in India of both free speech and creativity. The man in the photo, which is actually a still from video footage I took when I participated in an anti-CAA march on 10th January 2019 from Central North Calcutta to Gandhi’s statue near Chowringhee, is holding a sign saying ‘Bure din wapas karo’, or ‘Give us back the bad times’. It’s a plea containing a play on the BJP’s promise – or was it a threat – of bringing ‘achhe din’ or ‘good times’ to us. This joke creates a counter-nostalgia (what in the poet Kabir would be called ‘ulatbansi’: the ‘upside-down category’) that’s both an antidote to the BJP’s nostalgia for cultural purity and to capitalism’s upbeat but inequitable optimism.

The man holding up the sign is an everyday incarnation of a history of modernity in the Indian languages that the BJP denies and which the Anglophone Indian has, in the last three decades, forgotten and supplanted. The anti-CAA protests brought it back to us: a large, near-universal inheritance, little attended to – an older, richer resource for the secular than the Constitution or the English language. But it was also the cunning relocation of the Constitution and figures like Ambedkar and Gandhi (ordinarily available to many of us through the prism of Anglophone Indian liberalism) to Shaheen Bagh in Delhi and in Park Circus in Calcutta, where Muslim women sat for months in protest, that pointed, again, to the openness and adaptability of that inheritance: the vernacular legacy of a secular modernity that, among other things, took citizenship and free speech out of an English-as-a-first-language overseeing tutelage. This was liberating, and, as a critique, far more troublesome and unanswerable than anything the ‘liberal intelligentsia’ could come up with. It also grew clear that those who are religious – the implacable and astonishingly articulate women in burqas, for instance – are robust legatees of, and contributors to, the world-view we call ‘Indian secularism’. This is partly because they’re offspring of the sophistication of the modern Indian languages (Urdu, Hindi, Bengali etc); their speeches and sharp observations purify language of the violent bombast of the right-wing and of the self-congratulation of the ‘intelligentsia’. Who said that the religious aren’t secular? The religious taught us, at the end of 2019 and in the first months of this year, what ‘secular’ is. Then the pandemic came and put this revolution – not just a political but a cultural one – on hold. But a doorway has been opened for the first time in living memory, and we’ll see where it leads.