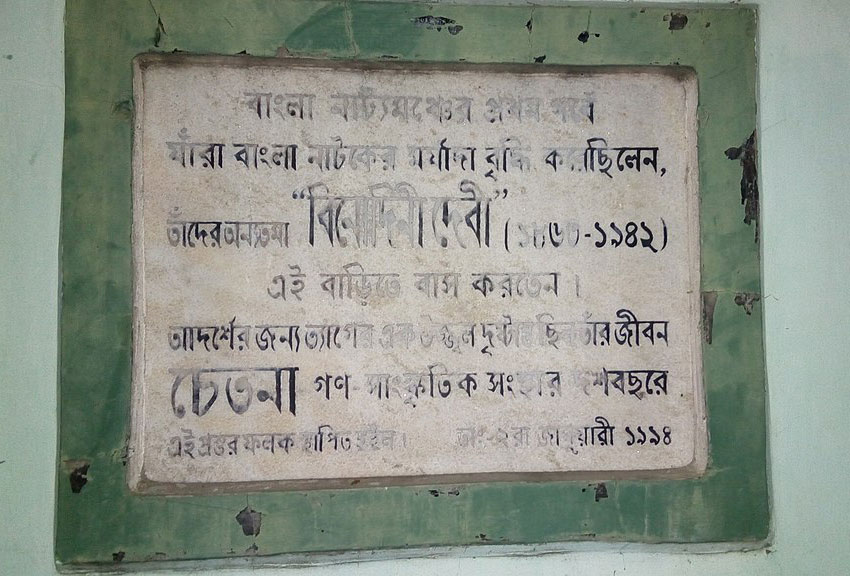

Original stone plaque on the house of the stage actress Nati Binodini, or Binodini Dasi (1863-1941), in Hatibagan, Calcutta. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The Treacherous Modern

Saikat Majumdar

Must the earliest experience of artistic representation be such a menagerie of the senses? ‘When you wet the bed first it is warm then it gets cold.’ Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus grasps life, at first, through sensations; time must pass before he can anything with abstract thought: ‘By thinking about things you could understand them.’

Sensations dominate. Is that why children like to draw? I did. The human form was sweet, slippery geometry till a teacher showed me how to infuse movement in muscles. The image of speed in the running boy was a great childhood milestone. And then signs of greater abstraction started to take over. Seeking to copy images from books, I would start to turn the pages, sucked into the story, forgetting the painting. A faraway narrative took me away from the immediate image.

One day in the teens my thick scrapbook of bright paintings emerged from a box under a bed, an army of caterpillars that became nothing.

In the end, words were safer. Not only were they quiet, but they offered the safety of an abstraction not visible to anyone. ‘He’s lost in a book,’ they would say, and leave me alone. Even when I started to write, it was far easier to hide it under the pretense of homework. You could not hide a painting.

Sensory art was spectacular, beautiful, and terrifying. My young mother trying to make a career in theatre, faltering, on stage and in her marriage. My child memory of watching her die in a cesspool of red light, youth-vision of her tied to the stake set to fire. Fight and gossip at home and in the neighborhood about what she could and she could not play, when in the evening she could go out, and when she couldn’t. My desire to grow up into an actor got buried in the fear of performance, in the vicious sound of quarrel, in the shame that drowned the stage.

Books were solitude, books were a hiding place. Reading made me anonymous, invisible.

I couldn’t have been more than ten when I came across an ornate, Sanskritic word for a woman’s breast in a novel by Bankim Chattopadhyay, in a description of rape and pillage by a village landlord. I had asked my grandmother – my mother’s mother – what the word meant. A curious smile glistened in her eyes. But without a fuss, she told me the meaning of the word, translating it into babyish Bangla. In the safety of books, no word was profane. Bankim babu, long a classic, had come a long way in a hundred years, from the time when girls had to hide his novels under their pillows lest someone caught them reading him.

Literature gave me solemnity, a weightiness of diction that misfired easily. I remember one twilight hour when my father left for an office trip and my mother spent several long minutes before the little shrine of gods and goddesses at home. After she finished praying and turned to me, I told her, with quiet and profound drama: ‘Father will never come back home again. Never again, mark my words.’ Sharply, she scolded me for such nonsense.

Why did I say something so stupid, words that sounded malicious even in the voice of a child? I’ve thought about it. I had realized that she was praying for the safety of her husband. I wanted to say something appropriate to the occasion. But I also wanted to say something dramatic, something that would conflict with the expected emotion of the moment. The fact that something would come across as ominous and painful almost became secondary to the need to sound oracular.

Literature built something around me. A safe space, an alternate home, a carapace? The private world kept fighting off everyone around, most of all those who wanted to come close. Is it strange that all my bookish memories are drenched in twilight? The sense of hours going by, the day gliding away, the colour of the sky darkening but not yet dark. I was nearing the end of A Tale of Two Cities, caught in the final emotional throes of the novel, when my mother asked me something. I snapped back, furious, fearful of losing the spell of the intense and frightful fictional world.

I was getting sucked deeper and deeper into the empowering solitude of literature. And the abstraction, the abstraction was crucial, because the reality around me was getting unbearable, more traumatic by the day. Solitude was also the reason why I did poorly in team sports such as cricket or soccer but excelled in more private games like ping pong and badminton, game for the nerds, as some say…

What got me into the high modernists in the last few years of high school? The beauty of their language, I thought at the time, with writerly aspirations beginning to come alive. The intensity of their sensory evocation sang through my body and struck a chord with the sensory overload that is every moment of life in an Indian city. That chord, not fully understood at that time, initiated my life in fiction, beginning with sketches of metro stations and city buses, of the odd habits of bus-conductors and squeegee boys, frozen, slow or messed up in time, expansive in space, much the way modernist poetry and fiction looked, felt like.

In college in St. Xavier’s, I entered the classroom of a poet-critic-publisher who had fought at the front lines of the battle that sought to make English believable as a language of Indian literature through decades of post- independence polemic. P. Lal made English a language of my literary dreams, etched the anxieties of tradition from T.S. Eliot to Vyasa, and published my first collections of short stories and novellas from Writers’ Workshop, the publishing house he had created. Rohinton Kapadia taught Joseph Conrad with the kind of care that would set a lasting pedagogic example. He introduced us to Conrad critics such as Albert Guerard and Ian Watt, and many years later, when I would join the English faculty at Stanford, where these two scholars were cherished as former members, the warmth of Professor Kapadia’s classroom would flood back to me. Partha Mukherjee set the trend for Joyce – no matter how much time I would spend with the author later in my life, his reading of ‘Araby’ set a defining rhythm to my approach to the author’s evocation of Dublin. Modernism was now a defining part of my bildung, as a reader and as a writer, as someone who wanted to see and feel the world and recreate it in his own way. I was keen to get started on that momentously titled book, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

In Calcutta, books circulated far beyond the conventional channels of publishing; piracy, and sometimes the xeroxing of whole books achieved in the 1990’s what free downloading websites would achieve in the 21st century. It was through this ‘unofficial’ network of distribution that I first got my hands on Amit Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address. That novel, and his second, Afternoon Raag, brought home the most perfect embodiment of modernist sensuality in locally realized Indian life that I could have imagined at that crucial moment of my life as a reader and writer.

I met with Chaudhuri in Calcutta, and he was to become Amitda soon after. Beyond sharing passion for Lawrence, Joyce, Mansfield, Woolf and other modernists, Amitda articulated his unease with the dominance of the national allegory that raged through the postcolonial world in the ‘80’s and ‘90’s, and the angularity of his own position as a novelist to that dominant tradition. These conversations would stay with me, help me define my own location as a fiction writer, and several years later, would shape the writing of a book that I would call Prose of the World: Modernism and the Banality of Empire.

Poets and writers like Chaudhuri and P. Lal, all in very different ways, shaped a living, working tradition of literature around me, of Indian literature written in English. But there was a longue durée tradition of which I felt a part, or perhaps just wanted to be, that extended to the modernists, as I imagined it did for Chaudhuri, Lal, and many other practitioners of Indian literature in English who were already part of literary history. At Jadavpur University for my M.A., I could have become an early modernist but the claim of modernism, in the end, would not be subordinated. Shakespeare floated over Jadavpur like a deeply intoxicating mist – in the passionate, humanist pedagogy of Sukanta Chaudhuri, the caustic blend of classicism and New Historicism offered by Swapan Chakravarty, the deconstructive approach of Supriya Chaudhuri, the performative poetics of Ananda Lal. But I finally read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and the most overwhelming need was to linger within an available, and practicable, tradition of fictional craft. Quieter lessons from my mother’s brother, Arup Rudra, who taught modern European literature and theatre in the same department, left softer imprints that proved secretly indelible. His translation of Jean Anouilh’s L’Alouette, with the title ‘The Bird of Fire’ in Bengali, would haunt me in many different ways till, many years later, I would write a novel with the soul of a play.

But at that time, I wrote about Calcutta buses the way I thought Woolf wrote about marks on the wall, Joyce about the alleys of Dublin – even as I dreamt of fleeing the city. But when I got away, Bowling Green, Ohio, turned out to be a flat nightmare, and a disembodying blank after the powerless multitude of Calcutta. I wrote formless short stories under the tutelage of Wendell Mayo, short story writer who loved Joyce and Ingmar Bergman, and Anthony Doerr, who would go on to win the Pulitzer a few years later with his novel All the Light You Cannot See. The MFA workshops were a daily struggle of understanding with my peers, all from the surrounding states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, Indiana – of Raymond Carver vs Joyce, of minimalism vs modernist lyricism, a tussle that leaves me embarrassed today.

But my longing for modernism needed a critical idiom. Making sense of myself as a reader and a writer, needed, for as long as I remember, criticism and scholarship as much as the practice of craft. That I got when I started working with Derek Attridge at Rutgers. Doctoral work was a large expansion, of the immediacy of literary modernism into the larger philosophical context of Enlightenment modernity, a tale of crisis and continuity. The soft easing of modernity into modernism – the celebration of eventless, quotidian life, the tedium of bureaucracy, the culture of flânerie and the colonial cityscape – much of these would energize the first book of criticism that I would write several years later, Prose of the World. But Derek would somehow push my love for Joyce into an appreciation of J.M. Coetzee, and I always think of my first novel, Silverfish published a few years before Prose of the World, caught in the midst of this back-and-forth journey – Joyce to Coetzee and back to Joyce again. Like the critical book, the novel, too, was a celebration of the landscape of modernity in the idiom of modernism, but it was also energized by the attempt of South Asian historians to retrieve a different language, that of minoritized voices lost to institutionalized narratives of history. Roaming the battered streets of Communist-ruled Calcutta and battling a corrupt bureaucracy to get his long-overdue pension, a retired schoolteacher reads a manuscript, the lost fragments of the memoir of a woman from colonial Bengal. The echoing of their tragedies became the subject of the novel.

Why do reassessments happen? Why are we pushed to rethink our relationship with books, traditions, forms of experience? One day, the American novelist Fae Myenne Ng told me, ‘The first five years are all you need.’ The first five years of life can shape an entire life of fiction-writing. It jolted me, and sought to stir something inside. But it was the experience of becoming a parent for the first time that took me back to the primal fears and joys and terrors and bewilderments of my own childhood. Parenthood, that terrible mess of screwed body clock and unruly body fluids and sleepless bitterness and inside-melting love, was one of the starkest disruptions of a clean and sensible life that I could remember since my own cloudy and traumatic childhood. It was a sudden call to break through the protective shell of abstraction that had grown around me, perhaps since the days when I slipped away from sensory forms such as painting and theatre to the rarefied symbolism of language. Quietness and solitude shattered inside my head like nothing before; privacy and isolation were ravaged in ways no adult could have done. Six months after the birth, I wrote this sentence: ‘Disaster came early in Ori’s life, at the age of five, the first time he saw his mother die.’ What happens when you are five years old and see your mother die on stage? What terror grips you, what tears?

The story of a young boy’s obsessive relationship with his mother’s life as on the theatre stage, The Firebird (published as Play House in the US) was the eruption of the primal, the irrational, the jaggedly sensory in my life – everything that would gash through the calmer narrative of quotidian modernity that had become my mainstay, and which I had celebrated in my first novel and my first book of criticism. It was, as it were, the rude appearance of the nonmodern in an artistic and intellectual life of modern equipoise. There was a narrative of modernity that I had accepted too easily in that life – the passage of the communal, sensory and the performative to the quite, solitary, and the linguistically abstracted. The oversimplification was mine no doubt, but mine it was indeed, and I had staked life and imagination on it. It took me almost five years to complete this novel with the soul of a play, but when it came out, I felt I had regained the performative and the multi-sensory in my artistic life much in the way I had sought to push them away when I stopped painting, and recoiled in terror from the darkness of the wings around the stage where my mother stood in a tiny pool of light.

Was my reassessment of modernity also a reassessment of my long obsession with literary modernism? Perhaps not, for what else did I have through which to invite the nonmodernity of performance, of violated kinship, but language itself, the modernist language that panted and foamed at the mouth to describe experience at the brink and beyond of language? Language that fell short joyously, in bruised delight? When I sought to describe the unsettling awakening of desire in a boys’ boarding school and their tentative experimentation with each other’s bodies, unmindful of terms such as straight and queer, some queer activists found the novel seeking to hush-hush queer desire under a heteronormative frame. But while The Scent of God, published a few months after the Indian Supreme Court’s decriminalization of homosexuality in September 2018, got caught up in a newfound celebration of queer literature, I saw, to a great extent, the flaws in my own binarization of the modern and the nonmodern. Encased in the ancient sensuality of Hinduism, this novel evoked the ambience of a monastic order framed in the swirl of the Bengal Renaissance, that great movement of colonial modernity. The abstract and the concrete were no stark binaries either, as some readings of the Enlightenment would have us believe. When does the ultimate abstract, God, give out a sensory scent?

Time has passed. The firstborn is now eleven. That eruption of that visceral experience has softened into the wonder of growth, both slow and fast, of the body, mind, and personality. What are the fears of a father who awaits a daughter becoming a woman? What odours, what phrases, what frowns and glances? This time, I choose a myth, an old story of mentorship that went to rot. The guru who took the pupil’s thumb as a honorarium only to have him do wonders with his middle finger. Is the modern an endless craving for the new? Or a reassessment of the old? Is the postmodern the digital remastering of the ancient? The Ekalavya story as a contemporary campus novel awaits daylight, as I slowly come out of a stark, adversarial reassessment of modernity that had fallen upon me, once upon a birth. The treacherous ellipsis of literary modernism is here to stay.

Saikat Majumdar is the author of three novels, The Scent of God (2019), The Firebird/Play House (2015/2017), and Silverfish (2007); a book of criticism, Prose of the World, a nonfiction, College, and a co-edited collection of essays, The Critic as Amateur. He writes a column in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Another Look at India’s Books, which discusses books from India that have escaped popular and critical attention. His new novel, The Middle Finger, will be published in January 2022