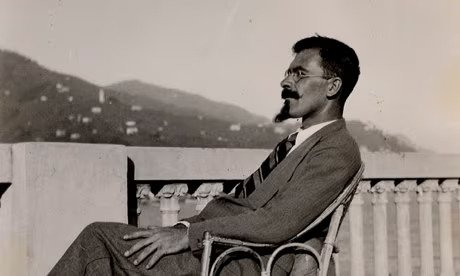

Basil Bunting on WB Yeats’s balcony in Rapallo, 1932. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

GHALIB, A DIARY: A NOTE BY ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA– An Excerpt from Book of Rahim, a new book in the Literary Activism series

Editor’s note: Book of Rahim is a collection of poems made up four sections, some of them comprising short-lived historic moments, some of them made up of fragments of autobiography. Mehrotra’s note below, which appears as a preface to one of the sections – the poem-sequence ‘Ghalib, A Diary’ –enquires into how the sequence came into being. If a literary work is ‘about’ anything, it’s about its own ongoing life. This note – less provider of context than hybrid artefact – is a reminder of this fact.

Ghalib wrote the Dastanbūy (Nosegay) between May 1857 and September 1858. It is his formal petition to Queen Victoria for the restoration of his pension, which had been stopped by the East India Company. Though described as a diary, it does not so much record as ruminate over the events of 1857. Given his military-aristocratic background, and seeing the destruction they had wrought on Delhi, Ghalib could barely hide his contempt for the rebels. At the same time, since this was a petition to the Queen, he could not afford openly to be critical of the British. His relations with them were already difficult because of his association with the Mughal court, which he frequently attended. Though his mad brother was killed by a British soldier, Ghalib conceals this fact in the diary, saying instead that his brother died after five days of fever. The actual cause of death we know from another account. Professor Khwaja Ahmed Faruqi’s 1971 translation from the original Persian is the basis of ‘Ghalib, A Diary’ – its incidents, details, often its very words are drawn from that translation. My other debt, broadly speaking, is to Basil Bunting’s ‘Chomei at Toyama’, which provided me with the form, the rhythmic pace, the inspiration to condense a prose work into verse. Like Chomei’s, Ghalib’s tone is elegiac; like Chomei, Ghalib belonged to the ‘minor nobility’. There are also, between the two works, profound differences. The communal divide, mentioned matter of factly in Dastanbūy, is entirely absent from Bunting’s poem, as is colonial rule. It’s not too much of a stretch to say that the poem has four authors: Ghalib, Faruqi, Bunting, and myself; though my job, as far as I can see, has been to stir the mix and serve, adding a few ingredients of my own. Ultimately, origins – ours, a poem’s – are, mostly, labours of love. And, like love, they are mysterious, unfathomable.

Dehra Dun

15 September 2021