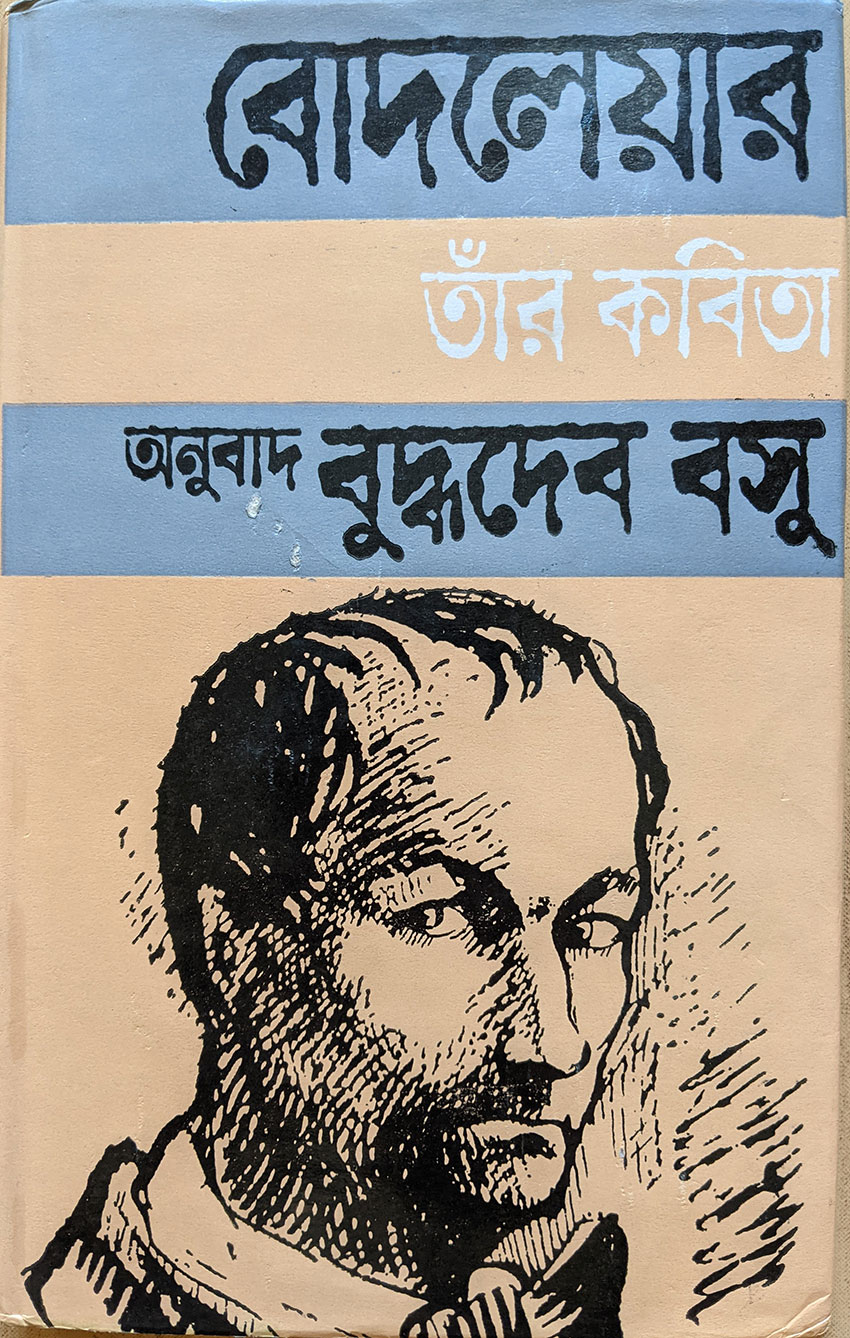

Cover of Sharl Baudelaire O Tar Kavita by Purnendu Pattrea (First edition, 1961)

The Bengali Baudelaire

Sumana Roy

Editor’s note: This essay was commissioned in connection with Baudelaire’s 200th birth anniversary. Buddhadeva Bose’s essay ‘Twins in Suffering: Baudelaire and Dostevsky’ appears in the Magazine section for the same reason. For the longer headnote, see here.

I was formally introduced to Baudelaire in the last year of the last century. I was a university student, and, the nature of such an introduction being what it is, chose to look away. There was something else: I kept imagining the professor who taught us the poems as Baudelaire. That made things incongruous – the short and sweet-spoken Professor Banerjee, with his stiff unmoving curls and his polyester shirt and well-meaning advice to students to drink Horlicks before their examinations, did not look convincing when he recited from Les Fleurs De Mal. Flowers of Evil was the opposite of Horlicks. I did not – and did not want to – care for either.

Then I came down with jaundice.

My working parents locked me at home so that I wouldn’t have to move up or down the stairs to open the door for them or visitors or postmen while they were away. The tasteless lunch was left within my reach, to save me from physical exertion. Addicted to the meagre university library that I had discovered for the first time in my provincial life, I missed books. Not necessarily reading them, but meeting new ones, a kind of tourism. I turned to my parents’ books, the few they had now. They were not really readers – on their shelves were mainly gifts from friends, as old as their marriage. I was sometimes envious of these creatures, that they had been with my parents longer than I had, but such moments were rare. Mostly I considered them boring – like I did my parents – not having bothered to read them. That is how I discovered Buddhadeva Bose’s Sharl Baudelaire O Tar Kavita.

It was the opposite of Baudelaire in the classroom. Though I could not imagine Buddhadeva Bose as Baudelaire, it was not hard for me to imagine Baudelaire speaking in Bangla at all. I knew only a little more about Bose than I did about Baudelaire then, and it might have been because of this that I read these poems as if they had been born in Bangla. This might have owed to my parents as well – they fed my brother and me the inexpensive Raduga editions of the Russian writers in a manner that it never occurred to us that Gorky or Dostoevsky were not writing in English.

Bose introduces the Bengali reader to Charles Baudelaire with an essay that is unlike anything that I have read on the French poet. It is often said that Bose was raised more by European literature than he was by literature in Bangla. That is debatable, but reading Lokenath Bhattacharya’s 1965 essay, ‘French Influence in Contemporary Bengali Poetry’, in the Sahitya Akademi journal Indian Literature, it is impossible to not notice, despite Bhattacharya’s blithe commentary, how Buddhadeva Bose’s poems work with and within an understanding of modernism through which he introduces the Bengali reader to Baudelaire’s poetry. Bhattacharya traces this legacy from Michael Madhusudan Dutt and Toru Dutt, the latter calling French ‘her favourite language’, to Pramatha Chaudhuri and members of the Tagore family.

Pramatha Choudhury [this is Bhattacharya’s spelling of the surname] speaks of his particular interest in the 19th-century French poetry but, surprisingly, never mentions a word about that century’s greatest single event concerning poetry : the symbolist movement. The poets he once casually refers to are Victor Hugo, Alfred de Musset, Théophile Gautier and Paul Verlaine. But why not also Baudelaire, especially when he cared to mention Gautier and Verlaine, both contemporaries of the poet of Les Fleurs du Mal? Verlaine, in particular, was not only a later poet than Baudelaire, but an inferior poet. And his indebtedness to Baudelaire is well-known. That he did not or forgot to mention Baudelaire makes one suspect that Pramatha Choudhury was perhaps not aware of the implications of the symbolist movement, its tremendous significance and potentialities.

Bhattacharya gives us a list of Baudelaire’s translators in Bangla: Arun Mitra, Bishnu Dey, Sudhindranath Dutta (to whom Buddhadeva Bose dedicates his book), before coming to Bose, but not before reminding us of this:

There has been much speculation, lately, about the possible French influence on Rabindranath Tagore. Some have tried to suggest a link between one or two poems of Tagore and the poetry of Baudelaire and Rimbaud. Irrespective of what has been said on the subject, Tagore was probably not aware of these poets or their poetry. Victoria Ocampo, in a recent article, gives a rather amusing instance of Tagore’s reaction to such poetry.

‘Another time,’ writes Ocampo, ‘I tried to translate for him some poems by Baudelaire… I read the “Invitation au Voyage.” When I came to Des meubles luisants/ Polis par les ans/ Décoreraient notre chambre;/ Les plus rares fleurs/ Mélant leurs odeurs/ Aux vagues senteurs de l’ambre/ Les riches plafonds,/ Les miroirs profonds,/ La splendeur Orientale…

Tagore interrupted me: ‘Vijaya, I don’t like your furniture poet.’

Though it is meant to be a record – and even a cursory investigation – of the influence of French poetry on Bangla literature, what we are often offered by Bhattacharya are unintentionally hilarious anecdotes that embody the climate – incurious and quick to generalize – in which Buddhadeva Bose would have begun translating these poems, as well as the bafflement to do with what this cross-pollination might result in. Here is Bhattacharya again:

It is interesting to speculate on how far the depressing living conditions in today’s Calcutta are responsible for the emergence of interest in such morbid aspects of French poetry as was Baudelaire’s. And then there is the example of a very reputed Bengali poet who openly declared at a recent informal gathering: ‘We have had enough of the vedantic ananda. What can now save us and our literature from the present stagnation is a rewarding knowledge of the sense of evil such as Baudelaire had.’

*

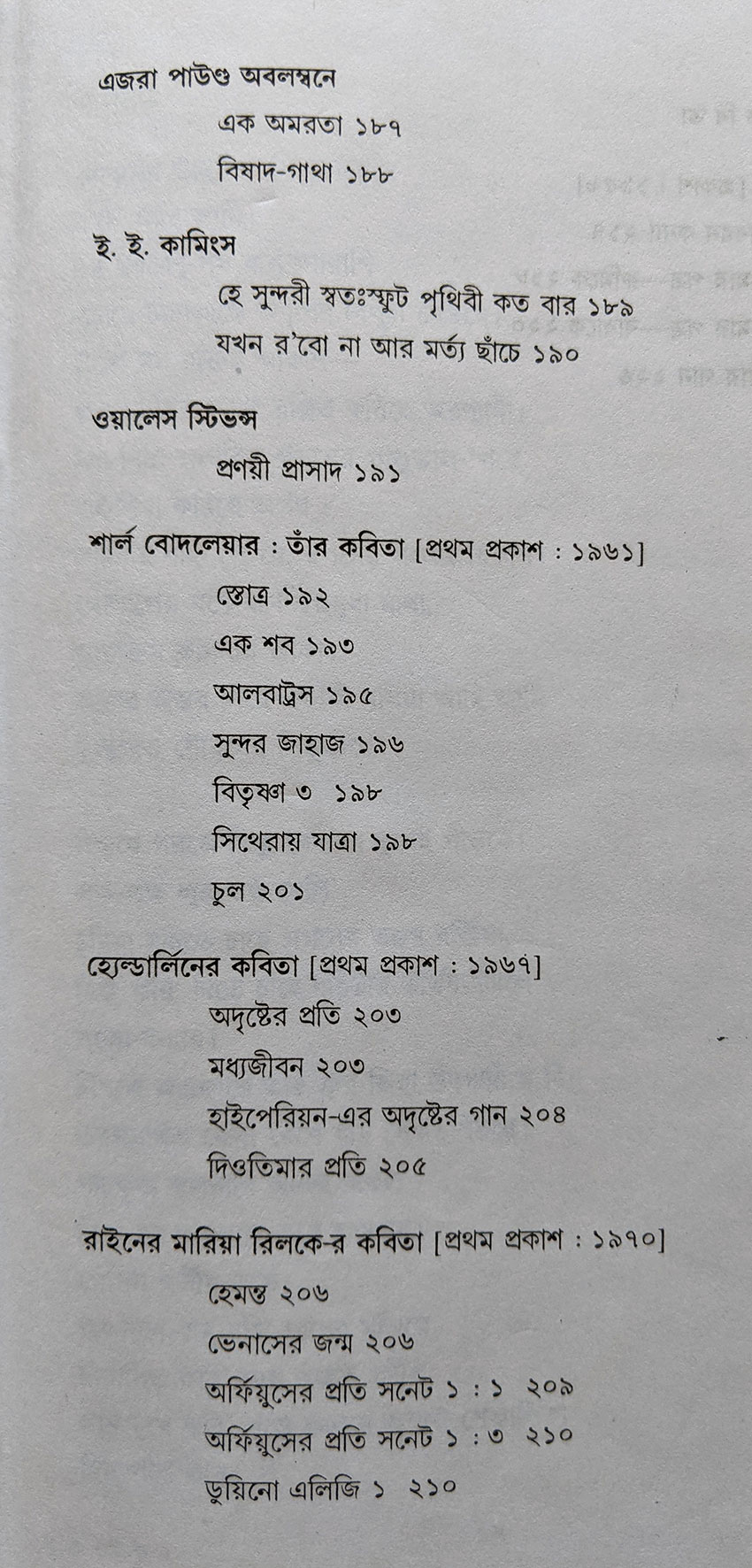

I do not know of any writer or critic who has ferried as many Western writers to Bengali as Bose has – they are everywhere, not just in his passionate translations, but in his fiction, dropping from the mouths of his characters, in the references and allusions and homages in his poems; and they are there in his many essays, records of his meetings with the writers themselves and sometimes with their work. And yet, in spite of his remarkable role as introducer in our literary history, his essay and translations of Baudelaire stand out. There is a quality of prescience about them. To give just one example – his defence of Baudelaire’s aesthetic and refutation of ‘obscenity’ in Sharl Baudelaire O Tar Kavita, which was published in 1961, seems like a premonition of the court case that he would have to fight for his novel Raat Bhor Brishti (It Rained All Night) in 1973. Going through the list of contents of his own selected poems (Shreshtha Kobita) one meets more writers than common nouns: Ezra Pound, e e cummings, Wallace Stevens, Hölderlin, Rilke, and, of course, Baudelaire.

From the list of contents of Buddhadeva Basur Shrestha Kobita – translations of Ezra Pound, e e cummings, Wallace Stevens, Hölderlin, Rilke, and Baudelaire

*

Buddhadeva Bose justifies his selection – he translates 108 poems from Les Fleurs de Mal – with these words: ‘Needless to say, I was unable to avoid the impact of my personal taste while deciding on the poems I have translated – why should I, after all? …’ He also distinguishes himself from Baudelaire scholars, saying that a book such as this one is for people like him, a ‘shadharon pathok’ (literally, an ‘ordinary’ reader, but most possibly a version of the ‘common reader’): ‘those who read poems because they love poetry’. This ‘translator’s note’, which precedes the voluptuous introduction, is interesting in a way few such notes are. Here we see a poet at work, one poet translating another, and, through the argument Bose makes for his selection, to do with poems and of words as well as structure, we are allowed entry into what are extremely private moments, moments so unconscious that they are rarely recorded. ‘Where the same impulse’ – Bose’s word is ‘prerona’, meaning ‘inspiration’ – ‘has led to the birth of four or five poems, I have, in some cases, chosen one or a couple of them.’ (All translations from Bose are mine.) This explains why he decides to include all the poems about death but feels no compunction (the word he uses in this context is ‘bibek’, conscience) about not including ‘Le Flacon’. Bose gives us a list of words that Baudelaire uses often:

There are words in Baudelaire that keep appearing and returning tirelessly: for instance, ‘ennui’, ‘funèbre’, ‘volupté’, ‘mystique’, ‘azur’. It is not possible to express them through the same Bangla word every time.

I read through the list – and Bose’s remarks on them, particularly where he mentions the ‘ananda’, or joy, that he found in this exercise – thinking, occasionally, of William Empson, wondering whether Buddhadeva Bose was familiar with his work, and, if he was, what he might have made of it. It is perhaps because this list and his selection of these words have a kind of Empsonian vitality about them.

I’ll confess that it is for Bose’s asides that I continue to go to the book. Here, in the image below, is one about his addition of two new letters (‘akshar’) to the Bangla alphabet, so that they can do justice to the English ‘z’ and French ‘j’/zh sounds (instead of just the ‘j’ and ‘jh’ sounds), as in the sound of ‘s’ in the English ‘pleasure’:

Buddhadeva Bose adds two new letters to the Bangla alphabet.

*

‘The first seer, king of poets, a real god.’ That is how Buddhadeva Bose begins his introduction, ‘Sharl Baudelaire O Adhunik Kobita’ (‘Charles Baudelaire and Modern Poetry’). Another writer might have told us right away that these words are Arthur Rimbaud’s about Baudelaire (in a letter he wrote to Paul Demeny on 15th May 1871), but Bose qualifies it delicately: ‘… as it is one poet’s opinion about another, it is precious even if it is an over-statement, even if it is wrong, (because only poets can respond in this infectious manner), which is why I begin my much-delayed essay with this familiar quotation.’

In these thirty-one pages is a history of literature imagined in the most unexpected way – a history of the modern constructed not through the constrictions of linguistic cultures but by the temperaments and compulsions of poets and artists. ‘Unmad’ and other Bangla words for madness and unreason appear a few times – the mad artist, the mad devotee, the intoxicated person, the uncontainable citizen. Bose, through his reading of Baudelaire, gives us a literary history of the modern, of how it was enabled by the madness and intoxication of certain artists who range across languages and epochs: he makes Baudelaire part of a family that includes Blake, Coleridge, the Bauls, Chaitanya and the Vaishnavites in Bengal, Hölderlin, Keats, Whitman, and Poe; a history of madness and, as he calls it, a history of ‘sadness’.

Both Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilisation and Bose’s Baudelaire were published in 1961.

*

I heard Marjorie Perloff speak in March this year about English translations of Baudelaire. She was delivering a talk – via Google Meet – at the University of North Bengal, the same institution where, in 1999, I had had to meet the French poet on the syllabus. Over the period of an hour, I listened mesmerised as Perloff, awake at midnight in Los Angeles, spoke about ‘infrathin’, a concept she was borrowing from Marcel Duchamp. She surveyed and investigated every word. Why ‘sawdust’ and ‘restaurants’ in ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, for instance? Soon, it was Baudelaire’s turn. Not Baudelaire, really, but his translators. From what I remember, she chose three translators in English, dismissing them from time to time, sometimes in the manner of a maths tutor whose students were just not able to get the answer right. This is from her new book Infrathin: An Experiment in Micropoetics.

One reason Baudelaire is so difficult to translate is that the rhymes—like astres/desastres —and rhetorical figures contain so much indirect and paragrammatic meaning. Here is the famous opening stanza of ‘Le Voyage’:

Pour l’enfant, amoureux de cartes et d’estampes

L’univers est égal à son vaste appétit.

Ah! Que le monde est grand à la clarté des lampes!

Aux yeux du souvenir que le monde est petit! …

‘Le Voyage’ is written in four-line stanzas comprised of alexandrines (the traditional twelve-syllable line, dominant in French poetry till the beginning of the twentieth-century), rhyming abab. But English, not being an inflected language, makes rhyming much more difficult, and few of Baudelaire’s translators have attempted to retain the rhyme scheme. Here are three translations, all of them by poets:

1. Roy Campbell:

For children crazed with maps and prints and stamps—

The universe can sate their appetite.

How vast the world is by the light of lamps,

But in the eyes of memory how slight!

2. Richard Howard:

The child enthralled by lithographs and map

can satisfy his hunger for the world.

how limitless it is beneath the lamp,

and how it shrinks in the eyes of memory!

3. Keith Waldrop:

For the child who likes maps and stamps, the universe is a match for his vast appetite. Ah! how large the world is in lamplight! In memory’s eye how the world is small.

Perloff commented on the inadequacy of each of these translations of ‘Le Voyage’ in English – her remarks were on form and arrangement, and also about the location of words, about how they behaved when placed beside, below, or far away from each other.

If it had been possible, I’d have liked to share Buddhadeva Bose’s translation of the same poem with her.

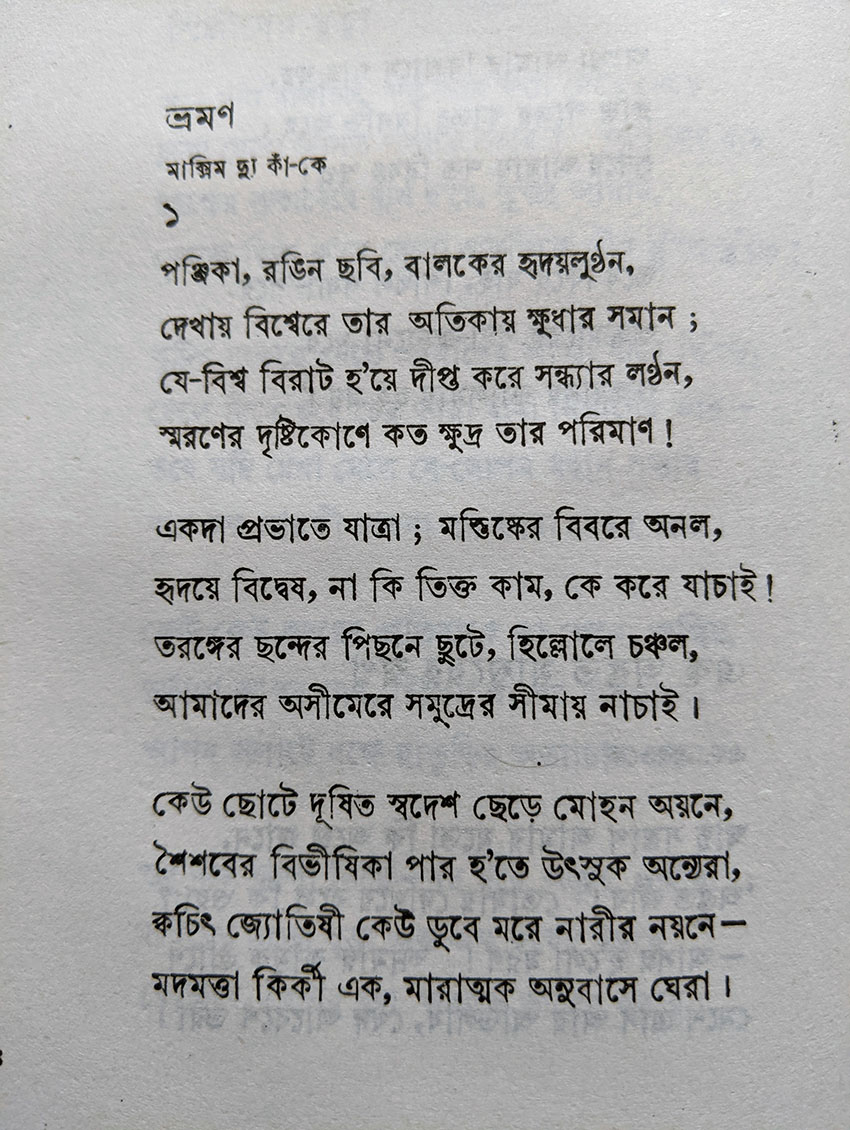

Excerpt from ‘Bhromon’, Bose’s translation of ‘Le Voyage’

He translates it as ‘Bhromon’. In terms of ‘content’, Bose’s translation would be closest to Roy Campbell’s, but the syntax is reversed: it’s not the boy but what he sees that Bose shows us in the first three words – ‘ponjika, rongin chhobi, baloker hridoy lunthon,/ dekhaye biswere taar atikaye kshudar shoman’. To translate into English from Bose’s Bengali: ‘almanacs, bright prints, plunder the boy’s heart,/ revealing a world equal to his gigantic appetite’. The singularity of Bose’s version, and the subtle, studied liberties it takes, has to do not so much with the difference in behaviour between English and Bangla, but the difference between ‘seeing’ and ‘reading’. It’s as if Bose wishes us to see the child and what the child sees simultaneously. The word ‘ponjika’ (almanac) also turns the boy’s home into a Bengali home while retaining the sense of voyaging that ‘maps’ brings – voyaging through time and destiny rather than, in this instance, through oceans.

As I reread some of these poems, comparing the English with Bose’s Bangla translations, I was reminded of my distance from the English Baudelaire and the immediacy of attraction I felt to the Bangla Baudelaire twenty years ago. The Bengali Baudelaire did not feel like a foreigner – he could begin speaking in medias res, like relatives do, as Bose’s Baudelaire does in ‘Albatross’. (I should add that Bangla, because it does not have articles, allows Bose to drop the article from ‘The Albatross’, which, too, helps to create a kind of directness that the presence of an article resists.) He begins his version with the expression ‘majhey majhey’ (‘from time to time’), as literary as it is drawing-room language. An English translator uses ‘often’ to open the stanza. ‘Often’ would be ‘anek shomoy’ in Bangla – more distant and official than the ease of ‘majhey majhey’. Sometimes it is just Bose’s use of syntax and the placement of the apostrophe that creates a world that one can enter without the restrictive codes that poems often have built into them.

Baudelaire’s ‘L’Ideal’ becomes ‘Beauty’ in the Penguin translation. In Bose, it is ‘Shoundorjyo’. The syntax of the opening line changes it all. ‘I am lovely, o mortals, a stone-fashioned dream’ it says in the English edition. In Bose’s version, it is ‘Mawrogon, aami je shundor; jyano pashaney swopnito …’ in Bangla (translated back into English: ‘Mortals, but I am beautiful; as if dreamt of in stone…’). By pulling ‘mortals’ (‘mawrogon’) to the head of the line, Bose is able to create drama and, thus, summon attention. Bose, in trying to modernise literary language, smuggles the sounds of everyday speech into these poems – the ‘gypsy’ in English is ‘bedouin’ in the Bangla; the words for ‘sailor’ change in the English translations, while in Bangla they remain ‘nabik’. I had, of course, met these words and their histories before – in Jibanananda Das, in the extraordinary poems (like ‘Banalata Sen’: ‘For thousands of years I have been walking earth’s paths/ From Sinhala’s seas in the night’s dark to Malay’s oceans’) where people walk and sail through time and history, making voyages of their own kind. Had he got the impulse to write these poems from Baudelaire as much as he might have from Tagore? Is Bose’s use of ‘ponjika’ in ‘The Voyage’ an acknowledgement, in turn, of ‘Banalata Sen’?

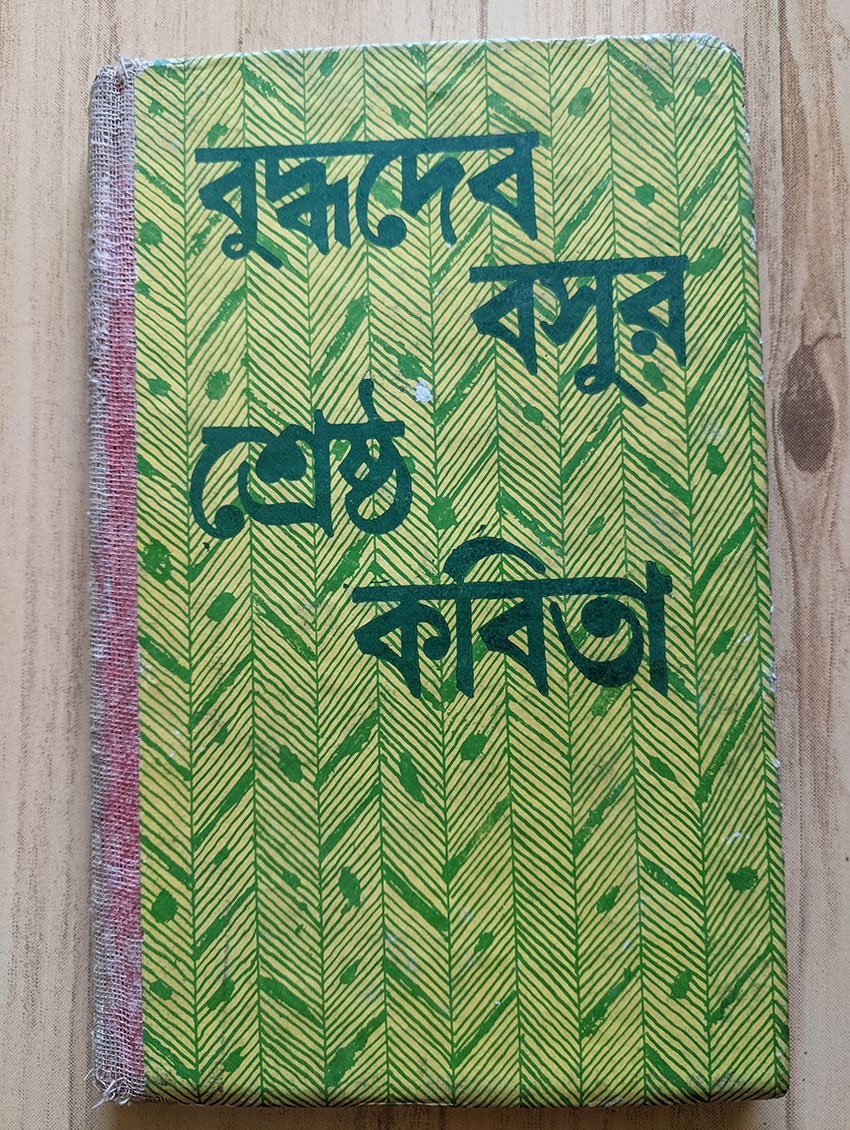

Cover of Buddhadeva Basur Shrestha Kabita

In Buddhadeva Basur Shrestha Kabita, Bose’s Selected Poems (edited by his friend Naresh Guha), Buddhadeva Bose begins his short introduction to the first edition with an anecdote. I find it telling that it’s about Rabindranath Tagore, with whose literary legacy he and his contemporaries had to argue in order to create a space for their own practice. ‘An autograph-hunter had once asked Rabindranath: “What, in your opinion, is the best book?” To this Rabindranath had replied, “Nature abhors superlatives.”’ Bose quotes Tagore in English, and then, agreeing with him about the silliness that attends the curiosity about ‘the best’ – to want to know about the highest mountain and the deepest sea is one thing, and the ‘best’ writer and ‘best’ book is quite another – he annotates Tagore’s response to include his: ‘Art abhors superlatives’.

Bose is writing this on a November day in 1951; but why must he begin his introductory note to his own poems in this manner? And why do I feel the need to share this in an essay about Baudelaire? Bose spends all his energy in this two-paragraph note to argue against the expectations associated with ‘shrestha’ – the best – that attend a title such as ‘Shrestha Kabita’. This temperament, of arguing with every single hand-me-down category or phrase, marks his creative life, and, indeed, his translations and selections from Baudelaire. Not only is there no attempt to please or conform; instead, Bose wishes to disturb, to provoke, to complicate. A writer who feels compelled to dismiss the idea of ‘shrestha’ for his own collection of ‘shrestha’ or ‘selected’ poems will naturally look at translation – and everything that it involves, the selection and rejection of every text and every word – as criticism. This is what informs Bose’s translation of Baudelaire – not the matter of fidelity to the original alone, but an acknowledgement of translation as criticism; as literary criticism. In the last half sentence of his short introduction to his own Selected Poems, Bose writes: ‘It is my belief that the problems to do with translating poetry comprise a special kind of test that poets have to pass …’

In Selected Poems, therefore, he makes a point of including his translations of European and American poets under the category ‘Anubad O Anulikhan’ (‘Translation and Transcription’), blurring the demarcation between his own ‘best’ or ‘shreshtha’ work and others’. Though I’m not a scholar either of Baudelaire or Bose, I have intuitively felt the impress of the French poet on this Bengali poet. Until a couple of years ago, I misread a poem by Buddhadeva Bose as being a translation of Baudelaire. This poem, ‘Sandhilagno’, is included in a section right before the short sections with Bose’s translations begin: that might have been one of the reasons I misled myself to believe that it was a translation of Baudelaire. Here is an excerpt from Bose’s poem in my inadequate translation – my aim is just to show the impact of Baudelaire, particularly his writing on death as a way of understanding modernity, on the poet Bose:

Sandhilagno

I don’t know my great-grandfather’s name.

My mother’s inaudible name comes to me with pain, with effort …

Ma, I touch your feet,

Ma, I kiss you, you unfamiliar, unknown, my unseen

Ma, save me. I, tired of the milk-less frustrated breasts, …

have weaned myself away from you,

searched for and snatched other nourishment,

because life is irrepressible,

and you are too embracingly affectionate,

You have abandoned me…

It is as if you never existed, or perhaps I’m not your intolerable labour anymore.

But now, in the dead of night, you are restless, curious …

No, I don’t know the name of my great grandfather. But my grandfather?

Have I inherited his talent?

Or his unjustified self-distribution?

I don’t know …

But today, in this friendless, sleepless silent night,

it seems that you’re the subtle wine in my blood, the dancing restlessness in

my heart, you mother, dead girl …

Your death has become an imagined painting, a mysterious sign,

because of which, after losing you, I have become capable, prosperous, not a loser,

filled my life with elemental humiliation

by loving poetry all my life …

Briefly, I also want to be a creator.

Ma, don’t laugh, please don’t think that I am an egoist.

I am just an enthusiastic lover,

Of words …

When I was young, I thought poetry was love,

Or an overflowing of lust,

A churning by stone to produce a more delicious butter.

But other thoughts have come to occupy me these days,

specially in these statuesquely silent nights,

loneliness makes me feel that even poetry is a trick – a consolation – only an alternative …

Ma, please don’t take these words to heart, this is merely my welcome speech.

I know that you are inexperienced, only a girl.

But you are dead, and I am so inexperienced and ignorant

about the ways of the dead that even imagination, there, becomes jaundiced.

So, if it’s possible, somehow,

Come to me once, I will see you; …

And there, over there, if you have learnt anything by now,

Something that is still unknown to me,

Then,

Tell me that too.

Having suddenly discovered this was one of Bose’s own poems, I wondered how I could have mistaken it for a translation of Baudelaire. Of course, I can’t really know. It might have been Bose’s acknowledgement – that the metrical structure in his translations are related to his own poems – that had stayed in my consciousness: ‘An alert reader will notice a variety of metres in the pages that follow; I’ve found great joy in being able to use some of the metres that I have been using in my poems … For some of the poems in Les Fleurs de Mal I have used … the rhythm of Baul songs ….’

As I write this, I am also thinking whether it might be the invisible tributaries of ‘Le Voyage’ and its own voyages through modern literatures – and my knowledge that Baudelaire had written the poem when living with his mother – that might have tricked me.

There might have been tiny remainders of Lokenath Bhattacharya’s essay in my mind as well: ‘That Baudelaire had knowledge, however vague, of Indian thought is beyond dispute. His work contains repeated references to India, and one of his poems is specifically addressed to “une Malabaraise.” He even once sailed for Calcutta, but the strenuous journey proved too much for him and he could not wait to reach the destination.’

I could see, even if only in a flash, how Baudelaire had become Bengali.

*

Apart from the similarities in their aesthetic proclivities, there is something else that links Bose to Baudelaire. As we live through an age of the professionalisation of translation, where the texts chosen for translation are often for commercial reasons – their ‘success’ on shortlists in other languages, or their content giving them topicality in a news-driven publishing ethos – I think of Bose and Baudelaire, two translators, one indefatigable, the other more restrained in his selection, one a Bengali translating the Europeans, the other a European translating an American, and I’m able to see through the fog of the present day: how translation was a means, often a desperate means, to claim a lineage, to take from those one was translating, to not be restricted by the chauvinism of language, to argue for and against those one was claiming as family. In Baudelaire’s translations of Edgar Allan Poe and Thomas de Quincey, particularly in the comments he writes to himself in the text of The Confessions of an English Opium Eater, is manifest a passionate effort to forge relations with strangers, with whom he could create and share a new vocabulary of the imagination. In Bose’s translations of Rilke and Pound – and, of course, Baudelaire – we cannot help noticing a similar ceaseless desire to bring into being a new aesthetic that could do justice to a world after Rabindranath. In spite of the joy of being allowed access to this hidden life, I close my copy of Sharl Baudelaire O Tar Kavita with some sadness – in this reaching out to other writers, in the obvious alienation they felt from their inability to share a common idiom of creativity with their immediate contemporaries, is, in page after page of these translations and the introduction, the restless aloneness of the artist.

Sumana Roy is the author of How I became a Tree, a work of nonfiction, Missing: A Novel, Out of Syllabus: Poems, and My Mother’s Lover and Other Stories, a collection of short stories.