Charlie Chaplin in The Tramp (1915)

THE WRITER AS TRAMP

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

Staring at you from innumerable photographs, their glossy hair combed back, writers can seldom be mistaken for hobos or tramps. If anything, they look more like men of action than men of contemplation, more men of the mechanized army than of the manual typewriter.

A 1960 photograph taken in the Russell Square offices of Faber and Faber shows T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender, and a young Ted Hughes. To be fair, none fits the description of an army colonel, serving or retired. While Eliot and Auden are having a chat, Spender smiles at the camera, MacNeice looks away from it, and Hughes, his eyes lowered, fixes his gaze on a distant spot on the floor, as though he wanted nothing more than to escape from the photograph.

That same year, 1960, Hughes published his second book, Lupercal. Stepping out of his office clothes as it were, he speaks in its opening poem in the voice of a tramp, whose material poverty, he suggests, is the source of his god-like power. Because the tramp owns nothing, he owns everything. ‘Rather than wash a good handkerchief he would beg an old one that was clean,’ is how W.H. Davies described one of the profession. For Hughes, the tramp is the very spirit of poetry. Like poetry, he can reside anywhere and bring the place to life:

All things being done or undone

As my hands adore or abandon—

Embody a now, erect a here

A bare-backed tramp and a ditch without fire

Cat or bread; and no shoes,

Honour, or hope . . .

(‘Things Present’)

Years later Hughes said in an interview that ‘Almost all the poems in Lupercal were written as invocations to writing. My main consciousness in those days was that it was impossible to write. So these invocations were just attempts to crack the apparent impossibility of producing anything.’

If you happen to run into a dry patch as a poet, the ‘sodden ditch’ (the phrase occurs in the poem’s last line, ‘dreams / The tramp in the sodden ditch.’) is not a bad place to be in.

In the opening essay of For Love and Money: A Writing Life 1969-1989, Jonathan Raban begins by saying that he’s ‘clocked up nearly twenty years as a professional writer’ and yet there are times when, asked what he did for a living, the word ‘writer’ does not come easily to him. To say it would be to open himself to a whole lot of other questions, and however frequently the questions are asked you are never quite ready for them:

Average-adjusters, lecturers in economics, shoe salesmen, property developers, don’t wince, shuffle and gaze distractedly at the ceiling when someone politely asks ‘And what do you do?’ For the professional writer that question (which is quickly followed by ‘Oh, should I know your name?’) is the prelude to a searching catechism of a kind more appropriate to a VAT inspector than to a fellow-guest in a drawing room. The safest response to it, if you can summon the requisite bottle, is to say ‘I’m a steeplejack’ and beam ferociously.

For most of my life, from the age of 21 to 65, I have truthfully said that I was a lecturer in English; a lecturer in economics would have been nicer. It always embarrasses me when people say that they know me in a different context. It’s as though, despite my efforts, word of my other activity had leaked out.

Why do writers want to be both visible and invisible, famous and anonymous? Why do they want to hide from the very public they want to sell their books to? Perhaps this has something to do with the nature of writing itself, especially poetry. The poet lives in a constant state of anxious sterility, a state of being a non-poet. The poems written in the past can only fill him with astonishment; they’re no guarantee that there’ll be one in the future. After finishing a book but before sending it off to his publisher, Thom Gunn would make sure that he’d started on his next. And Hughes, as we saw, felt he may not be able to produce anything after The Hawk in the Rain.

Poets are in a better position than most to go into the mystery of writing, its sources and processes, though poetic composition is a subject that is ultimately unknowable. There is no other profession I can think of (to describe writing poetry as a profession for a moment) where the job description asks you to do something that is outside the realm of thought, ‘always beyond / / your own intelligence’ as Les Murray put it. ‘Poetry is not like reasoning,’ wrote Shelley, ‘a power to be exerted according to the determination of the will. A man cannot say, “I will compose poetry.” The greatest poet even cannot say it; for the mind in creation is as a fading coal, which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness.’ Echoing the Shelleyan wind and the crackling fading piece of coal, the American poet Randall Jarrell said ‘A good poet is someone who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times; a dozen or two dozen times and he is great.’ Wikiquote helpfully also provides you with a small picture of forked lightning and storm-tossed trees on its Jarrell page. The picture can be enlarged.

Ask a poet what he does all day, and if the answer is that he spends his waking hours waiting for an inconstant wind or standing out in imaginary thunderstorms expecting to be struck by real lightning, you’d only feel sorry for the guy. Better to say that you’re not a poet at all. No, you’re nothing of the kind.

A form of collective anonymity was practised by the hundreds of poets who, for over half a millennium, wrote and sang poems that they attributed not to themselves but to the 15th century North Indian poet Kabir. The phrase ‘Kabir says’ or ‘Says Kabir’ occurs in thousands of songs that are still being composed, keeping alive the tradition of composing anonymously. Written in the vernacular, in our version of ‘plain American which cats and dogs can read!’, the Kabir corpus continues to be a work in progress. We’ll never know how many poets contributed to it or the size of their individual contributions, but even if they contributed just one or two, the songs caught on, and as they passed from singer to singer, who freely changed words and sometimes whole lines, they became part of the body of work that we recognise as Kabir’s. Since it cannot with certainty be said of a single line in the corpus that it’s been written by him, it is safe to assume that the entire corpus is the creation of anonymous amateurs, or amateur-masters, men and women too humble to attach their names to songs that by ‘some invisible influence’ they composed as they went about their daily chores. Some of them would have been low-caste artisans like Kabir, who was a weaver. But whatever their profession, by calling him the author of the songs and merging their identity in his, they ensured, without being aware of it, that though their names will be erased from literary memory their songs will survive.

For different reasons, anonymity also appeals to the Australian writer Gerald Murnane. He says in ‘Secret Writing’:

I would like my next book to be published with a pseudonym on the cover. Better still, I would like the book to be published with no author’s name on it. But I would like more than that. I would like all books of fiction to be published without their authors’ names. I would like all writers to be secret writers. Then, readers would read books with more discernment. I believe many readers are too much influenced by the names on the front of books.

Looking back at the nine years he spent as ‘a secret writer’ working on his first book, Murnane says that he was then ‘more free to write what pleased me,’ and, what seems equally important, ‘nobody ever asked me to look at their own writing and to comment on it.’ Another writer who reflected similarly on his days of anonymity and freedom, and with whom Murnane is sometimes compared, is Samuel Becket. He wrote to his American publisher Barney Rosset in November 1958:

I feel I am getting more and more entangled in professionalism and self-exploitation and that it would be really better to stop altogether than to go on with that. What I need is to get back into the state of mind of 1945 when it was write or perish. But I suppose no chance of that.

Though his publishers, Giramondo in Australia and Dalkey Archive in the United States, and reviewers, who include J.M. Coetzee, describe him as a writer of fiction, Murnane doesn’t see himself as one. In the Author’s Note to his essay collection Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs he says, ‘I should never have tried to write fiction or non-fiction or even anything in-between. I should have left it to discerning editors to publish all my pieces of writing as essays.’

By first dispensing with the author’s name and then with conventional literary categories, what Murnane is suggesting is that the author should be free of the grip of the marketplace and the expectations of the reader, which in the Anglo-American publishing world amount the same thing.

Most of Murnane’s essays refer back to his own fiction. In one of them called ‘Why I write what I write’ he lets us into his writing method: ‘Every night before I start my writing I read aloud what I wrote the night before. I’m always reading aloud and listening to the sounds of sentences.’ But what is he listening for when he reads aloud? ‘The answer’, he says, ‘is not simple.’ Quoting Hugh Kenner, Robert Frost, and Robert Louis Stevenson, he says ‘I don’t say that I swear by any of these maxims that I’ve quoted. But each of them lights up a little part of the mystery of why some sentences sound right and some don’t.’

Every time you put pen to paper you participate in an ancient rite, in which words call up other words as spirits call up spirits. This is the rite of writing, that no one quite knows how to perform to perfection until it is performed. You then test it by intoning the passage to yourself and paying attention to your ear—and your gut.

*

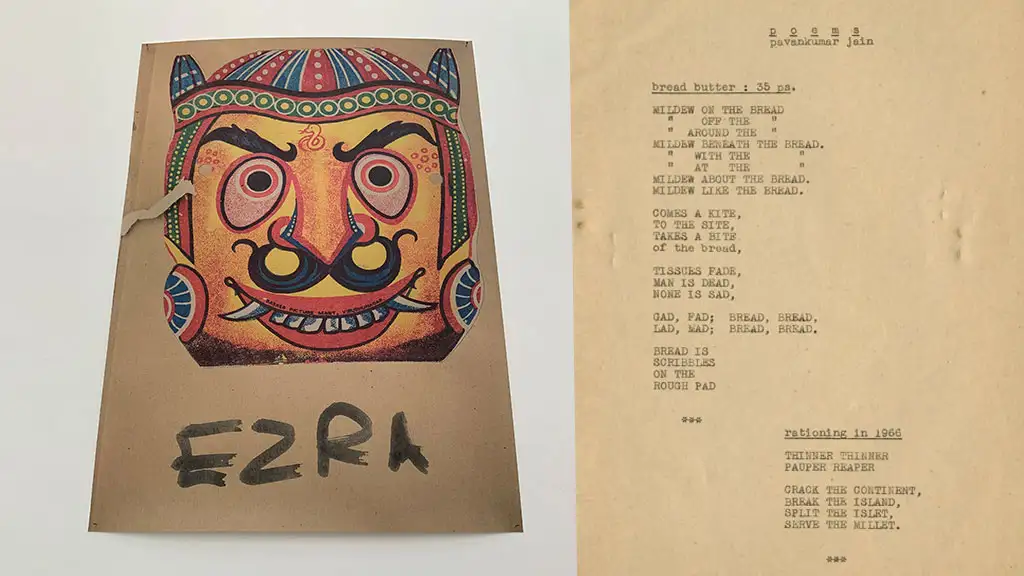

In as much as he did his utmost to make his books impossible to buy, a task in which to his everlasting credit he succeeded when he was alive, the bi-lingual Indian poet Arun Kolatkar was a secret writer. He had a suspicion of contracts and any request from publishers to bring out his book-length sequence of poems Jejuri , which had appeared in 1976 from Clearing House, a publishing co-op of which he was a member, was ignored. The Clearing House Jejuri had a print run of 750 copies that sold out when the book won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize. Subsequently, it was reprinted by Kolatkar’s Marathi publisher, his old friend Ashok Shahane, who had set up Pras Prakashan in 1977 with the sole purpose of bringing out Kolatkar’s first Marathi book Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita. The arrangement with Clearing House and later with Pras suited Kolatkar. There were for one no contracts to sign, and he had complete control over the design and layout of both his books. The only flaw in the arrangement was that Pras, like Clearing House a small press, did not have the distribution, and Jejuri was only ever available at Strand Book Stall in Bombay. In the 1980s and 1990s it was also often out of print, sometimes for years at a time. I’d then ask Kolatkar to find out from Shahane when he’d be reprinting it, and Kolatkar would assure me that he would. But he never did, though he and Shahane met three times a week and spent hours in each other’s company. The problem of the book’s unavailability persisted, until Kolatkar took matters into his own hands. He began to ‘pirate’ it. He had discovered a photocopier who made perfectly respectable lookalikes of Jejuri: square format; front and back covers that were colour-photocopied; black endpapers. These he was quite happy to give away to the more persistent of his admirers.

Though you can now order the NYRB Classics Jejuri over the internet, the Pras edition, when it’s not out of print, can be bought in the same distinctive format and design that Kolatkar chose for it 40 years ago. OUP had offered to bring out Jejuri in Three Crowns and as a concession even waived the necessity of signing a contract. All they asked for was a letter from Kolatkar giving permission to publish the book for a limited period. Kolatkar, astute as ever, showed no interest. As it turned out, the more robust publisher, the biggest university press in the world, with branches in Auckland, Cape Town, and Dar es Salaam, dropped its poetry list in 1999, while a book put out by a one-man small press from a two-room flat in Malad East, Bombay, is still around, or was until recently.

Arun Kolatkar sometimes reflected on what it is to be Arun Kolatkar. From the day he started writing in the early 1950s until his death in 2004 he wrote in two languages, Marathi and English, and came up with strikingly different metaphors—different from Shelley’s and Jarrell’s—for poetry and poetic composition. I found the following notes while preparing a posthumous edition of his uncollected work. Scribbled on pieces of scratch paper that in Bombay are sold by weight, they were stuffed inside a brown envelope that made no mention of the contents:

I have a pen in my possession

which writes in 2 languages

and draws in one

__

My pencil is sharpened at both ends

I use one end to write in Marathi

the other in English

__

*

Whether half my work will always remain invisible

like the other side of the moon

whether a reader in one language will have to be content

with the side facing him

Whether my work is 2 bodies of work in spite of their common origin

which have developed independently of each other

each with its separate history

ecology life forms

spin rate of spin temperature tilt tilt of axis

atmosphere

each moving in its own orbit

occasionally influencing each other causing anomalies

in motion or occasionally eclipsing one another

causing tidal waves tides

A pencil sharpened at both ends the bilingual poet waits

will he write his next poem in English

will he write it in Marathi

which language will he write the next poem in

will depend on which way his pencil points at the piece of paper before him

what will he do if he wants to write a poem in Chinese

find a pencil which points three ways

buy a new pencil brush

There is a neural selector switch in my brain

first I press the on button

when I see the light pilot light

I press the selector switch

How do I write in 2 languages? On alternate days

Am I two different animals or just one with a striped skin a piebald

*

You need a double barrelled gun to shoot a bilingual poet

one bullet in the head will never be enough to kill meyou need 2 bullets to kill me for I’m two beasts

you’re hunting / tracking not one but 2 beaststhough our tracks may crisscrossand we may come to the same waterhole to drink

and to the same saltlicks

there are two distinct scents we useto mark the boundaries we hunt in different parts of the jungle

though our territories may overlapor sometimes when our paths cross we may pass through each other

exchanging some our characteristics in the process

A puzzling figure even to himself, in these notes Kolatkar tries, through metaphor, to understand who he is, or what he is. He is among the finest English-language Indian poets of the last century, while to his Marathi admirers, those who can see the other side of the moon, he is the true successor to the great 17th century Marathi poet Tukaram. The English poems and the Marathi poems exist independently of each other, ‘each with its separate history / ecology life forms’. When you look at some of Kolatkar’s manuscripts you find lines and phrases scribbled in English and Marathi on the same page, as though Kolatkar was flipping the pencil ‘sharpened at both ends’ as fast as he could, trying to keep pace with the bi-lingual flow of his thoughts.

The ‘history’ and ‘ecology’ of the English poems and the Marathi poems may be separate, but both drew in unexpected ways on the same wide reading spread over the two languages Kolatkar wrote in. Bhijki Vahi (2003), which translates as Tear-stained Notebook, consists of individual poems and sequences, each about a mythical or historical woman who had witnessed or otherwise known extreme suffering. They range from the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis and the pagan philosopher Hypatia to Nadezhda Mandelstam and Susan Sontag. He wanted very much to write on Heliose, but despite reading everything he could on her and Abelard, he could not find the glimmering historical detail that, in his retelling, would make the fiction of poetry seem like plain historical fact. The books that helped Kolatkar enter the worlds of these women (some of the books bought second-hand from Bombay’s pavement stalls, which he never walked past without stopping to check what they had) were drawn from the world’s literatures: Innuit folktales, the Rig Veda, the New Testament, Homer, Virgil, Edmund Gibbon, Farid-ud-Din Attar, the Chinese translations of

Arthur Waley and Alain Danielou’s Shilappadikaram, Nadezhda Mandelstam’s autobiographies. Then there are the newspaper clippings that were the sources of yet other poems. One of them is the sequence called ‘Kim’, a reference to the nine-year-old Kim Phuc fleeing her village outside Saigon after a napalm attack, the moment captured in Nick Ut’s famous 1972 photograph.

It would seem from the above that the poems in Bhijki Vahi were written in English, but they’re in Marathi, the winged Marathi beast—at 393 pages Kolatkar’s longest book—emerging feather by feather from the skin of the English one, the language in which he did his reading for the poems.

‘Bilingual poets may exist / a bilingual poem doesn’t’ Kolatkar says in another note, yet ‘Kshamasookta’ [Pardon Poem], one of the poems in ‘Kim’, is bilingual. It’s the only time that the paths of the ‘two beasts’, Marathi and English, crossed in print. The poem’s structure is a double refrain, two two-line stanzas in Marathi alternating with one two-line stanza in English. Here are the English stanzas. The speaker is Kim:

It’s alright, nameless pilot

I forgive, I forgive

It’s alright, John

I forgive, I forgive

It’s alright, General

I forgive, I forgive

It’s alright, Uncle

I forgive, I forgive

It’s alright, Nick

I forgive, I forgive

After forgiving Nick Ut, Kim forgives History, then each of the four directions by name, then Everybody. Last, she forgives Kolatkar, the person writing the poem:

It’s alright, Poet

I forgive, I forgive

‘I have a pen in my possession / which writes in 2 languages’, Kolatkar said. But then he said something else too: ‘and draws in one’. It is the only such reference in his writing. Though Kolatkar’s line is as unmistakable as Saul Steinberg’s and has the same playful quality, he chose if not to erase it at least take it in another direction, sacrificing art in order to pursue poetry. How many gifts can a man juggle? And there’s also the matter of securing a livelihood.

Kolatkar, who had been painting from the time he was in school in Kolhapur, had studied at the JJ School of Art, Bombay, which he joined in 1949. V.S. Gaitonde was a few ahead of him, Tyeb Mehta was his contemporary. He quit JJ School in 1951 without completing his diploma. Sometime in the latter half of 1953, the painter Ambadas introduced him to Darshan Chhabda. They met at the Artists’ Aid Fund Centre in Rampart Row, and Darshan remembers that Kolatkar had with him a book of Dylan Thomas’ poems. They got married the following year.

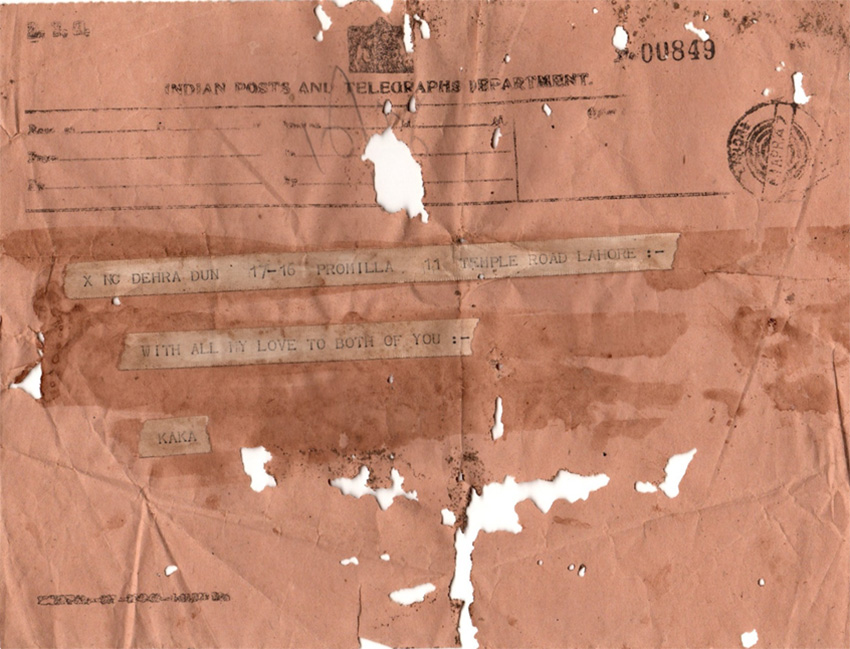

Darshan Chhabda came from a wealthy Punjabi family originally from Pakistan. They owned cinema theatres in Ahmedabad and Bombay and her brother, Bal, directed at least one film, Do Raha(1952), in which the artist character is played by M.F. Husain. Bal had been to Hollywood to learn film making, but referred to the experience in self-deprecating terms. He was a flamboyant character, easy to get along with. Husain introduced him to his painter friends—Raza, Gaitonde, Mehta, Padamsee, among others – and he was soon part of the group. Around 1954, he started to paint himself, and, not so much for investment but because he wanted to help the painters, he started to buy.

As a struggling 23-year-old art student who had given up his diploma midway, Kolatkar, when he married Darshan, would have been only too aware of the background she came from. They themselves had very little money and lived in lodging houses, moving frequently. Kolatkar responded to an advertisement for an office peon and for a while worked in a Malad toy shop, painting wooden toys, a job Husain had got for him. After a year of living like this, in which Kolatkar published his first poem in Marathi and his first poem in English, they decided, in 1955, to leave Bombay and move to Madras.

From what I can recall of my conversations with Darshan, though she never said it in so many words, the move seems to have been for the good. They had new friends, the city’s Tamil and Telugu poets and writers, and Kolatkar was productive, writing new poems in both English and Marathi. He painted pots and tried to market them, and was still on the lookout for a regular job. There was a small allowance coming in from Darshan’s mother that would have made things easier for the young couple.

The initial opposition of their families to the inter-caste and inter-class marriage by now seems to have eased. The non-Brahmin Chhabdas would have seen Kolatkar, a college dropout, as another penurious painter; the Brahmin Kolatkars would have seen the Chhabdas as flashy upstarts. It was a case of the Bombay film industry, around which there then hung a slight air of disrepute, meeting the stern district inspector of schools, which Kolatkar’s father was, though he was far from stern. ‘c is for chhabdas / grossly grossly’ Kolatkar wrote light-heartedly in his love poem ‘an alphabet for darshan’. Darshan and Arun were back Bombay in 1957, when Arun finally completed his JJ School diploma, standing first in order of merit. In June of that year he joined Ajanta Advertising, the first Indian-owned advertising company, as a visualiser. The transition to advertising is mentioned in ‘an alphabet for darshan’; it comes immediately after the reference to the Chhabdas: ‘c is for copywriting / bravely bravely’.

In 1988, 31 years after he entered the profession, Kolatkar was inducted into the Communication Arts Guild Hall of Fame. The price of going into advertising was that he abandoned painting, but if he paid a price he also came at a price. Kolatkar knew what he was trading, and he didn’t come cheap. In the words of the song he wrote, set to music, and recorded in his own voice, he had decided that he was not going to be ‘a poor man from a poor land’: ‘i’m a poor man from a poor land and everything about me is wrong / my guitar is warped my voice cracks but i’ve written a damned good song’. Or as he wrote in another poem, ‘i’m god’s gift to advertising’.

Kolatkar gave up painting but not drawing. In 1969 he privately published The Policeman: A Wordless Play in 13 Scenes in a silkscreened edition of under 10 copies; maybe just five, or three. The name he gave his small press was papertiger. In 2005 when Pras reprinted The Policeman, it said on the flap: ‘These sketches were done in 1969. Very few copies were made. Only one of them could be located. The originals too could not be found.’ Inside there’s an acknowledgement to Vrindavan Dandavate, a friend of both Kolatkar and Shahane: ‘Thanks to Vrindavan for preserving the copy of The Policeman for all these years from 1969 through to 2005. Till now this was the only copy on the planet. But for him the book couldn’t have seen the light of the [sic] day.’ It has still not seen much light of day because Pras gives a low discount, making it unprofitable for bookstores to stock it. (For the record, there is at least one more copy of the papertiger edition that I know of.)

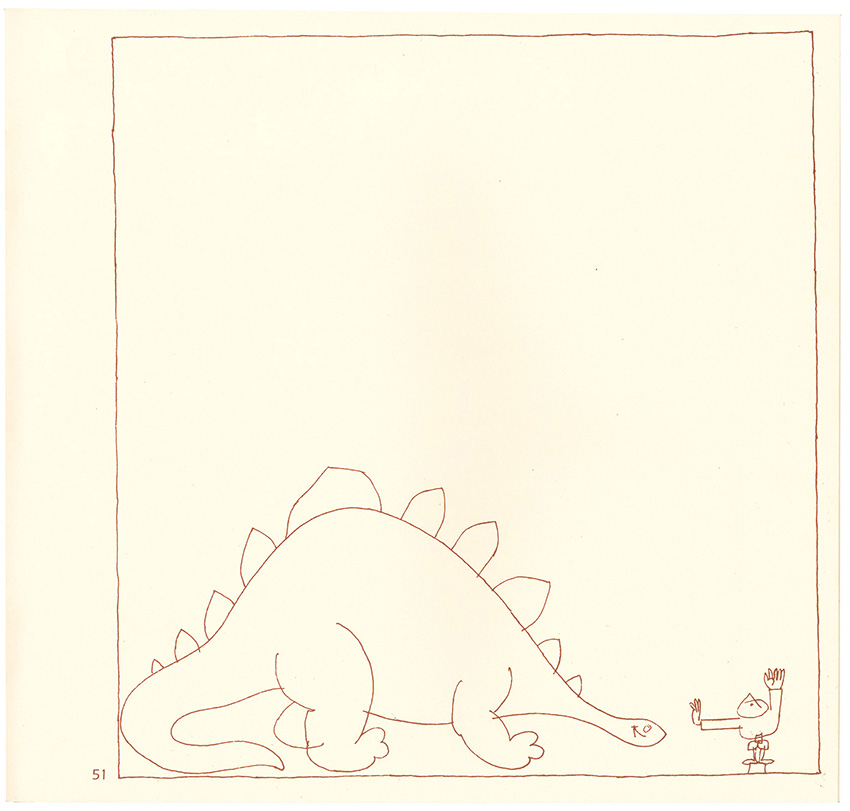

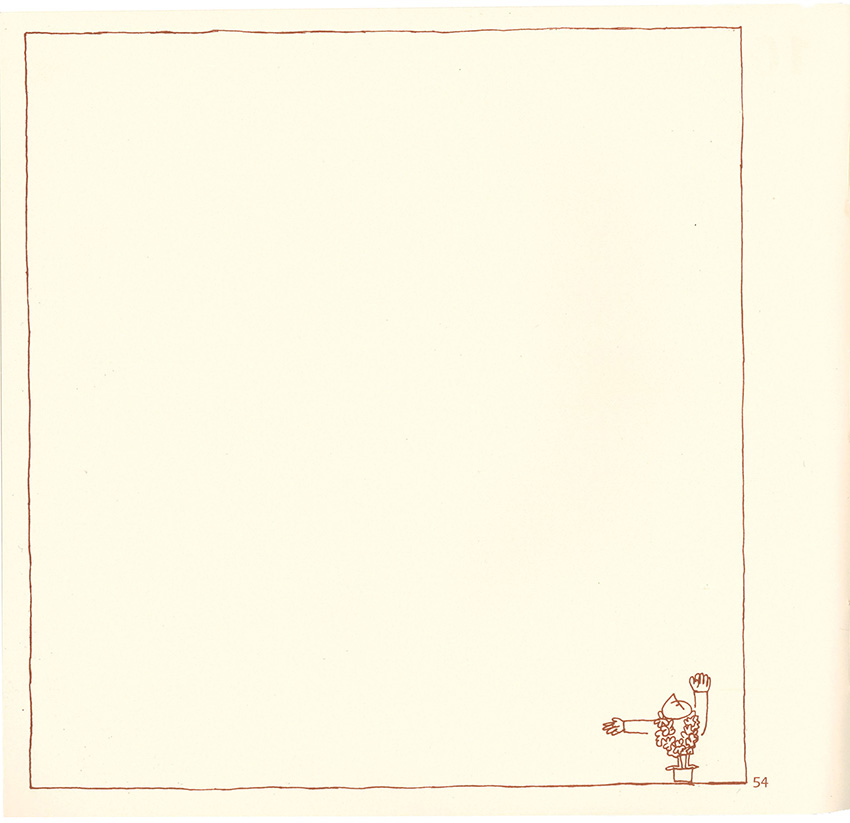

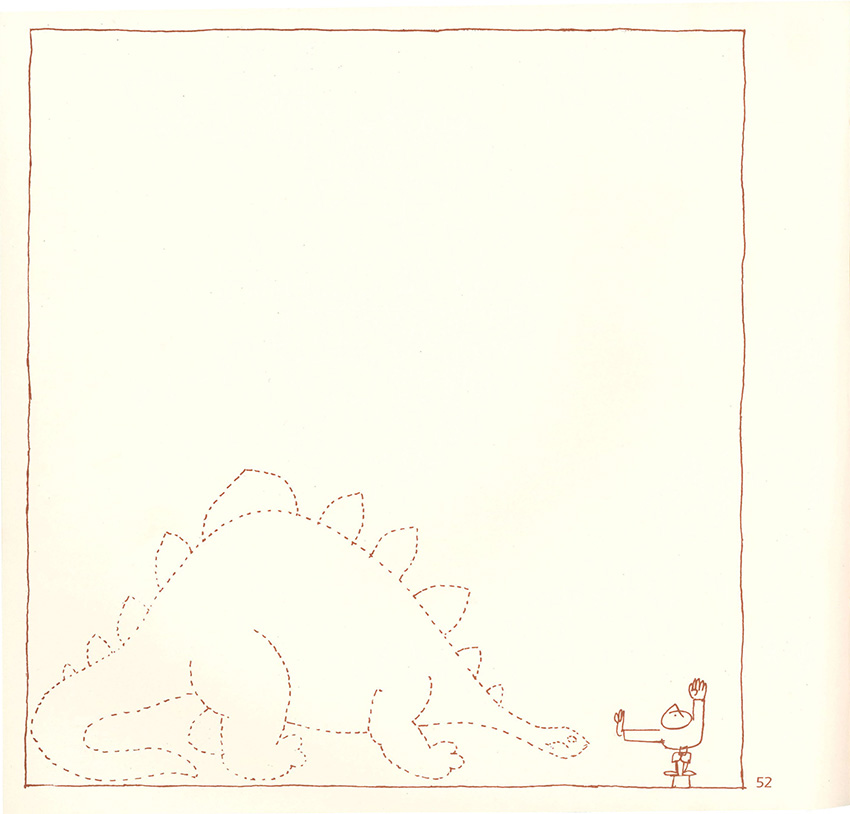

Each of the 13 scenes of The Policeman is a self-contained set of drawings about the adventures of a Bombay traffic policeman. In scene 9, for instance, in the first picture, bottom right, we see his tiny figure in forage cap and half-pants (which is how he is depicted throughout the book), left arm raised and the right stuck to his chest. In the left corner, many times his size, is the suggestion of a dinosaur: a narrow head, a long neck, a thick leg, four bony plates along the back.

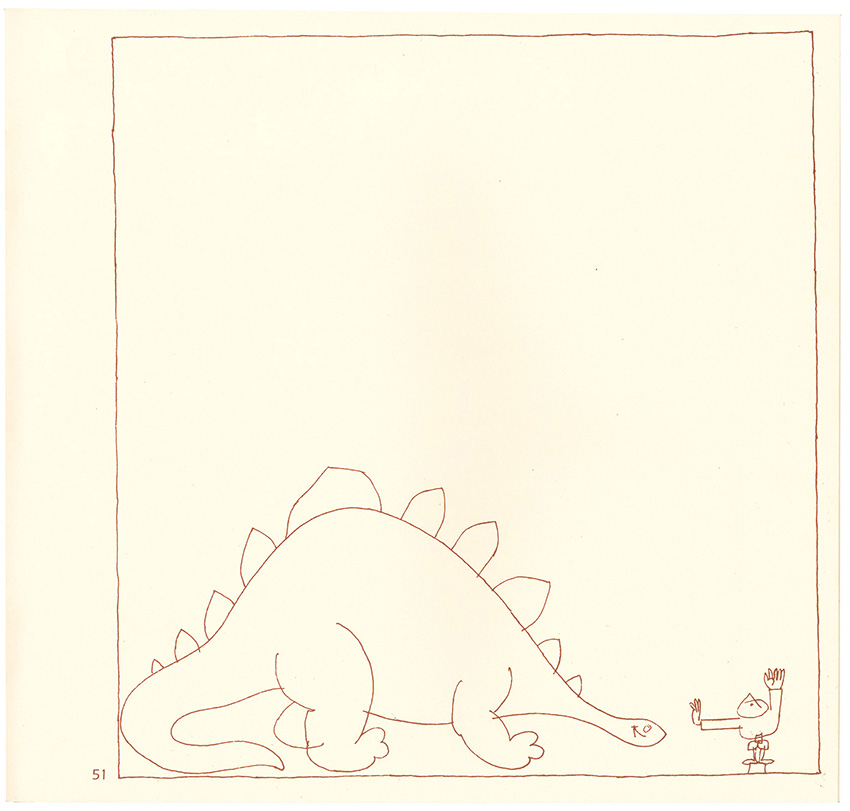

In the next picture the policeman stays where he is, in the bottom right corner, but he has changed his hand gesture. His right arm is outstretched and the palm is raised, stopping the dinosaur in its tracks. The dinosaur is now in full view and occupies most of the lower half of the page.

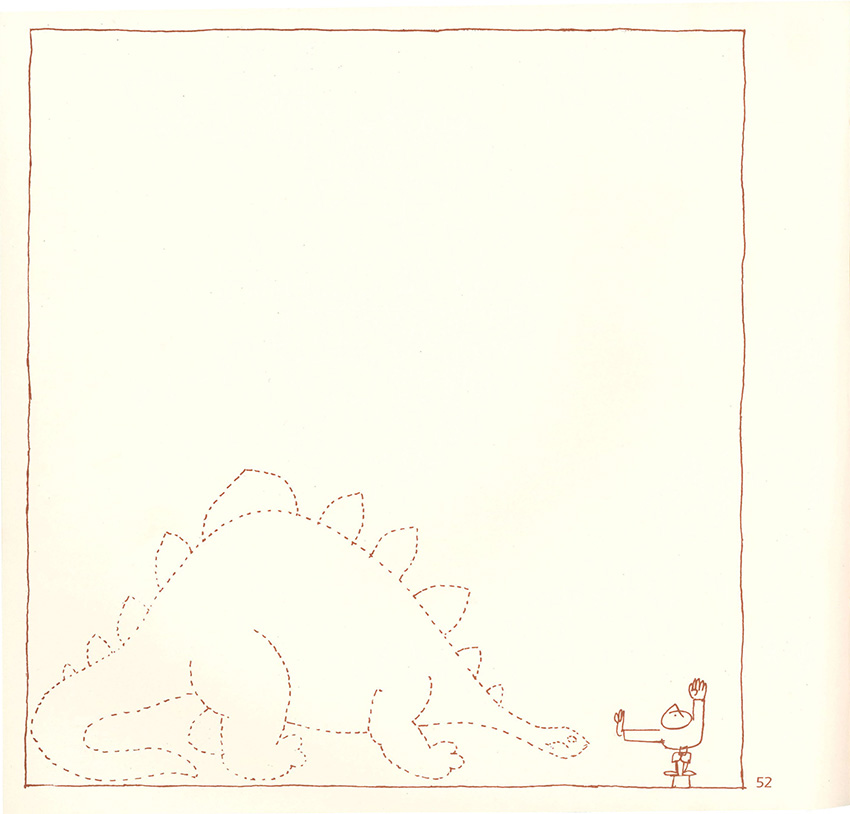

In the third picture there is no change in the policeman’s hand gesture, it still says Stop, but the dinosaur is shown in broken outline, to indicate it is beginning to decompose.

In the fourth picture the dinosaur is scattered pieces of bone arranged to look like the reconstructed dinosaur we see in natural history museums; above it is a crane’s hoist line and hook.

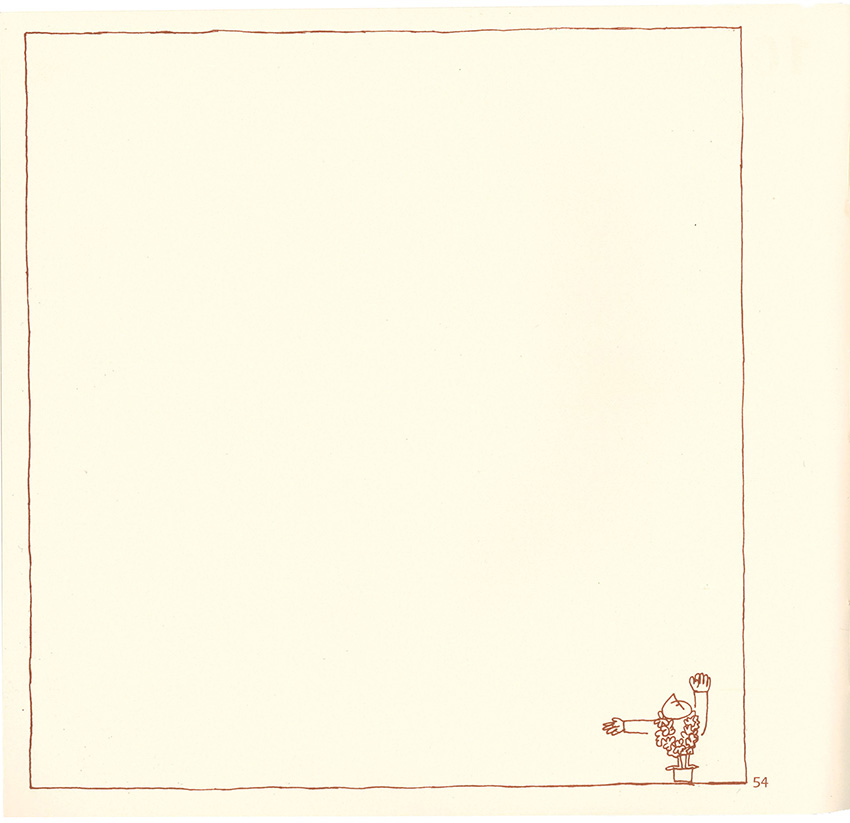

In the last picture there’s no sign of the dinosaur and the page is blank except for the policeman in the bottom right corner. His one arm is raised, one outstretched, and there’s a big garland round his neck.

It would be a mistake to see The Policeman as a children’s book, unless you are thinking of children who can appreciate, along with the strong narrative, the economy of drawing, the eye for detail (the forage cap), the juxtapositions (dinosaur bones and crane), and the artist’s sympathy for and alertness to what is generally overlooked (the unsung traffic policeman), the same qualities that we find in Kolatkar’s poems, from the early ‘The Hag’, about an old woman devouring oranges (‘She likes them baggy’), to Kala Ghoda Poems published a year before his death. Kala Ghoda is a Republic Day parade of street characters, in which the policeman would not have felt out of place. Bringing up the rear of the parade is ‘The Boomtown Leper’s Band’:

Trrrap a boom chaka

shh chaka boom trap

Ladies and gentlemen (crash)

here comes (bang), here comes (boom)

here comes the Boomtown Lepers’ Band,

drumsticks and maracas tied to their hands

bandaged in silk and the finest of gauze,

and clutching tambourines in scaly paws.

Trrrap a boom chaka

shh chaka boom trap

Whack.

Kolatkar was a secret writer, even more a secret musician and artist, and it’s not as though he did not know what it is to be a secret tramp. For him, the ‘sodden ditch’ and the lack of bread and footwear were not Hughesian metaphors.

Kolatkar’s younger brother Makarand, who was then a schoolboy, well remembers the day in March 1953 when two unshaven men, who to him looked like sadhus, walked into their Poona house. When they sat down to eat, it was as though they hadn’t had a proper meal in weeks. The two men were Kolatkar and his friend Bandu Vaze, returning after a roughly 200-kilometre walk that, starting from Bombay, had taken them to Kalyan, Nasik, Rotegaon, and Kopargaon. The journey into western Maharashtra, done without any money, seems like a test of endurance. Kolatkar describes it in his poem ‘The Turnaround’, though why he undertook it is never explained, except declaratively in the first line:

Bombay made me a beggar.

Kalyan gave me a lump of jaggery to suck.

In a small village that had a waterfall

but no name

my blanket found a buyer

and I feasted on just plain ordinary water.

I arrived in Nasik with

peepul leaves between my teeth.

There I sold my Tukaram

to buy myself some bread and mince.

When I turned off Agra Road,

one of my sandals gave up the ghost.

‘It was walk walk walk and walk all the way’ Kolatkar says, the weariness reflected in the repetition. There are references throughout to hunger and begging for food (‘I knocked on the first door I came upon, / asked for a handout’), and once it led an awkward moment (‘There I got bread to eat alright / but a woman was pissing. / I didn’t see her in the dark / and she just blew up. / Bread you want you motherfucker . . .’). There’s famine in the countryside and Kolatkar sees ‘a dead bullock.’ He comes to ‘a big town’ and gets his first news of the outside world. This is how we know where he was and what he was doing on the morning of 7 March 1953. An individual beggar or tramp walking along dusty village roads (‘Dust in my beard, dust in my hair’) is seldom part of recorded history nor is it news, except when the tramp is also a poet and records the moment in a line of verse:

Kopargaon is a big town.

That’s where I read that Stalin was dead.

Kopargaon is a big town

where it seemed shameful to beg.

And I had to knock on five doors

to get half a handful of rice.

A famished man reading about the death of Stalin: would the irony have struck him?

Darshan, who first met Kolatkar a few months after he returned from the journey, thought of it as a watershed both in his life and in his life as a writer. The poems he wrote at the time, 1953-54, were always called the ‘journey’ poems. One of them, ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’, the very first poem he published in English, refers to an incident also recounted in ‘The Turnaround’, when in Rotegaon ‘a dog died in the temple / where I was trying to get some sleep.’

‘The Turnaround’ was written first in Marathi in 1967, fourteen years after the walking journey it describes, the title taken from its opening line, ‘Mumbaina bhikes lavla’ (Bombay made me a beggar). The English translation came twenty years later, in 1987. In ‘Mumbaina bhikes lavla’ /‘The Turnaround’ you can hear, like an echo, Frank O’Hara’s ‘The Day Lady Died’, which Kolatkar would have read in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry: 1945-1960:

It is 12:20 in New York a Friday

three days after Bastille day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine

because I will get off the 4:19 in Easthampton

at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner

and I don’t know the people who will feed me

‘Literature is news that STAYS news’, said Ezra Pound. The news that is literature is received by poetry lovers in one way; by its practitioners, wherever they are, in another. Literary geographies run counter to real ones. New York and the interior towns of western Maharashtra could be part of the same country. It’s the only country worth having patriotic feelings about.

Whether he was walking through the streets of Kala Ghoda, on his way to the Asiatic Library or to Wayside Inn or to Strand Book Stall, or getting in and out of taxis, Kolatkar, in faded t-shirt, five-pocket jeans that he’d keep pulling up, and shod in a sturdy pair of unpolished shoes, retained about him the air of a tramp, albeit a stylish one.

*

You can plot a story but you cannot, or not in the same way, plot a lyric. Fiction writers have sometimes said that when they close shop for the day they try and do so at a point from where they can resume the story the next morning. If a poet tries to do this, it is only to realize the next dreaded morning that there is no plot to resume, no poem to go back to, the poem having collapsed under its own gibberish in the hours when the poet was asleep, sweetly dreaming. More often than not, the poet wakes up to the nightmare of the blank page that was only recently seething with words. This can happen with fiction writers too. They too can find that the fictional property they had developed over weeks and months has disappeared before their eyes, leaving little trace. If writing is a profession, then, surely, there’s none other like it.

A traditional skill like pottery can be passed down from parent to child, but writing is not that either. To some extent, as writing schools must believe, it can be taught, not taught from scratch but certainly to a person who is already some way along to becoming a writer. This student writer can be suggested a few small changes, tentatively offered, that in the opinion of the teacher may improve the piece of writing. The student is free to reject the advice, hence the tentativeness. In most professions, on the other hand, there is one right way of doing things, which is clearly laid out. If you do not follow the instructions exactly as given, the car come for an engine overhaul will not start or the bridge you were supervising will collapse. There are several things you could try to make a flat piece of writing work, but only one way to repair a flat tyre.

For all these reasons writing can only be a non-profession, or rather too much of one. A writer cannot call in sick, go on vacation, have weekends, or even have a meal peacefully without mentally rushing off to his desk to redo a sentence. I became aware of this about 25 years ago when I was chided by my wife for never taking a holiday. She was right, but I could not tell her the reason for it, that while I had one profession by day, as an English lecturer, I had another one at night, a pursuit that I kept hidden from the world, including her. There was a third person in our marriage, and that person was writing. The poem about our unacknowledged ménage à trois is called ‘Domicile’:

For the slashed cheek

And puckered knee

And unkept vow,

But as much for

The trips not made

To places of interest –

Like the Stone Age site

A bus ride away

In Mirzapur District –

Accept in recompense

This cone of light

In whose spell I sit,

A mechanical pencil

Gripped in my hand,

Like a microlith.

This was first delivered as a talk at the ‘literary activism’ symposium held at IIC Delhi in January 2016 and later reprinted in Translating the Indian Past and Other Literary Histories (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2019).

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra is the author most recently of Selected Poems and Translations (NYRB Poets) and, as editor, The Book of Indian Essays: Two Hundred Years of English Prose (Black Kite).