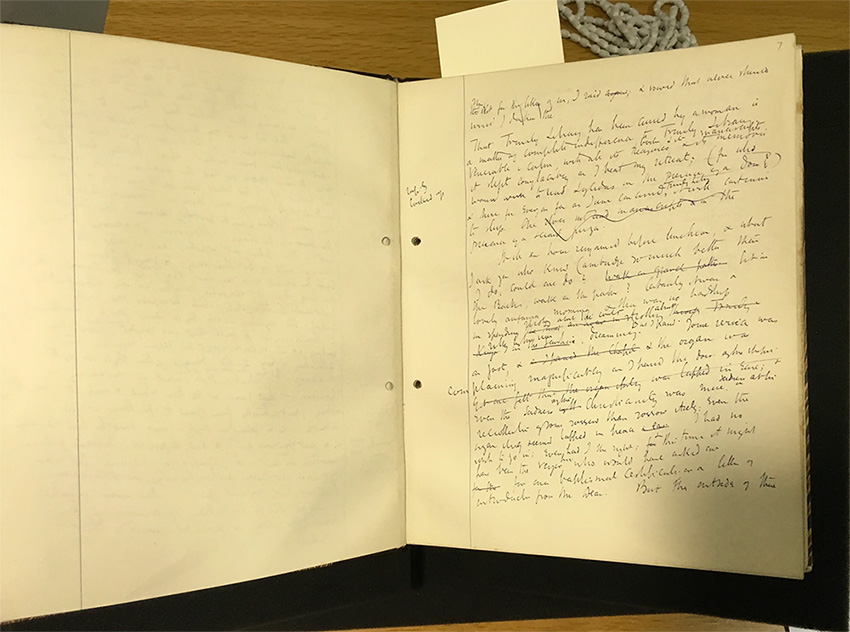

A manuscript page from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. (Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

The Writer-Critic and Literary Studies: Mission Statement

Despite Socrates’s imputation that the great tragic poets didn’t know what they were up to and why they were up to it, writers and creative practitioners are often deeply self-reflexive, which is why their contribution to criticism has been formative and radical. I’m thinking of Socrates’s near-contemporary Bharata; Abhinavagupta and other rasa theorists from the 8th to the 10th century; in the same line of thinking several centuries later, Wordsworth and Coleridge; Eliot, Tagore, and Woolf and the theorists of modernism; the anti-humanist Lawrence; the American New Critics; the Bengali poet Buddhadeva Bose and the Kannada novelist U R Ananthamurthy, both of whom taught literature – ‘comparative’ and ‘English’ respectively – for much of their lives; Nabokov, of course, lecturing at Wellesley College; William Empson; in our time, the Irish poet-critic Tom Paulin, who taught at Oxford; Arvind Krishna Mehrotra and his many years at the University of Allahabad; Charles Bernstein, Joan Retallack, Anne Carson, and Rosanna Warren, all of whom have taught outside of creative writing departments at North American universities; others not mentioned in this hastily put-together list. The New Critics – Ransom, Tate – may have been among the first to have found a home in literature departments and to teach literature for a living while attempting to write it, and about it. The demands of livelihood may have made this necessary; but the idea (to what extent it was realistic is open to question) of the possible freedom and idealism of literature departments at a certain point of the twentieth century may have also drawn writers to them.

We have been in a different place since the 1990s and the onset of economic deregulation. For one thing, we have forgotten how literature was experienced before deregulation, and, for those of us who studied it at university, how it was taught. We’re aware of the cultural turn represented by the emergence of critical theory and, in the 1990s, of cultural studies (although even that memory is fading, and many of us now might believe that literature was always cultural studies), but we neither connect these turns as rigorously to globalisation, the collapse of the Left, and deregulation as we should, and nor do we connect them to the vanished everyday markers of literary studies from forty years ago. For instance, many of my teachers, when I was both an undergraduate and graduate student in the 1980s, were Misters and Misses rather than Doctors. Many of these teachers – and these Misters and Misses, like Dan Jacobson, Gay Clifford, John Fuller, and Jon Stallworthy – were writer-critics or poet-critics. The bifurcation of pedagogy by the end of the 1980s, especially in America, meant writers who gravitated towards jobs in institutions would henceforth teach creative writing and craft and (because they didn’t have PhDs) be kept out of literature departments, and teachers of literature themselves would be entirely professionalised – that is, inducted into a self-perpetuating system. This meant that literature was no longer taught by poets or novelists; in an offshoot of counselling, they provided ‘feedback’ to students on craft and/or character. Increasingly, ‘literature’ itself ceased to be a site of productive engagement for academics who had jobs in literature departments. Writers – whether they were eighteen or fifty years old – forgot, in the meantime, that what had brought them to writing was not their devotion to their own work but the excitement of literature. These shifts are in some ways more important than the so-called theory wars and the attempts to formulate post-theory positions, or developments like ‘world literature’ or even ‘decolonisation’, all of which run the danger of slipping into institutionally mandated discussions – partly because, through a combination of deliberate oversight and a mutual pact between academic and writer, the latter no longer contributes self-reflexively to the form of thinking we still invoke constantly and continue to call ‘literature’. We often ask why the humanities and literary studies departments have become shells, or are in crisis. We don’t ask what impact the marginalisation of writers has had on literary pedagogy and scholarship. The impact, both for imaginative writing and literary discussion (which includes the teaching of literature), has been transformative.

It’s neither possible nor desirable to return to some version of a golden age; to close down creative writing departments, to proscribe discussions on craft undertaken en masse, to make the mandatory doctorate for teachers of literature obsolete, and to ask writers to participate in fashioning a vocabulary for what it means to encounter the problem of literature, and read it, in the present day. In what way, then, can writers return to literature, and literary studies, and vice versa? Are either writers or literary studies ready to pursue this line of thinking? Would recovering a history of criticism beyond the academy comprise a starting-point? Are there locations, within and outside the academy, that can be identified as being possible venues for the writer-critic-teacher-of-literature? Or are writers in a uniquely promising position, with the potential to open things up, as was the case with modern artists from different parts of the world in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in relation to what then was the orthodoxy of the academies of art?

Amit Chaudhuri, October 2022