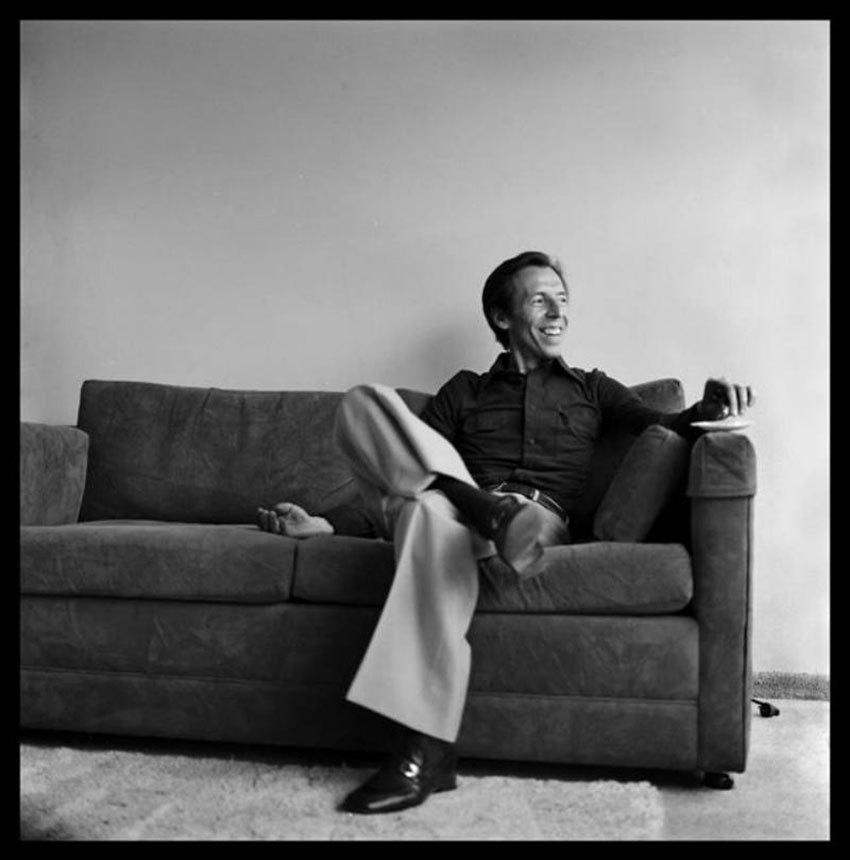

Julio Ramón Ribeyro, 1974. Photo: Alicia Benavides. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Ribeyro – a short story

Amit Chaudhuri

This is a response to Antonio Muñoz Molina’s The Hour Of Ribeyro

I had just sat down in a train going to London when I heard a muffled ding and knew an email had come in. It was from Pankaj Mishra: he had sent me a link to a ‘recent reconsideration of the Latin American novel’ which he ‘thought… would interest you… Especially, this paragraph…’ What followed was a quote – elliptical ruminations that caught my attention but whose provenance was unclear: ‘“The literary ostentation of many Latin American writers. Their complex of coming from peripheral, underdeveloped areas, and their fear of being taken for uneducated. The demonstrative will of their works… Prove that they can also encompass an entire culture and express it in an encyclopedic sheet that summarizes 20 centuries of history. Nouveau riche aspect of his works: heteroclite, monstrous, ornate mansions…”.’

When I opened the link, I found the essay was in Spanish. But I wasn’t sure if it was an essay or a story, partly because of the lines in the quote: ambitious but fragmentary; historically acute but also solipsistic and dreamlike. ‘I guess you’ve selected parts of sentences in the quote, then translated them?’ I wrote back. ‘Anyway, it makes for an intriguing assemblage. I read long ago that Marquez wanted to bring in bad taste too, among other things, to his fiction. But – and I may be wrong – these writers seemed to have often brought in something [altogether] more conventional [instead]. Sadly, I can’t read the article as it’s in Spanish. Much interesting critical work going on in the non-Anglophone world – including Bengali, even today.’ (The ‘altogether’ and ‘instead’ appear in square brackets because I have only just added them.)

Pankaj replied that he had, in fact, translated the short essay in its entirety. He was learning Spanish; it was his first attempt at translation. I found the full text he then sent me (on the body of an email) invigorating. A living writer, Antonio Muñoz Molina, had written about a dead one, Julio Ramón Ribeyro, and about Ribeyro’s daily journal in particular, to which belong the discontinuous sentences quoted above. It was as if I could hear myself in the essay; as if not only my voice but my and others’ history as writers – a history I’d almost lost interest in – was being returned to me. I had, through a bit of cosmic mistiming, been fated to write my short plotless novels in the age of the global novel, of the great ‘Indian’ novel, and in 1999 I’d spoken about ‘the tautological idea that since India is a huge baggy monster, the novels that accommodate it have to be baggy monsters as well… Indian life is plural, garrulous, rambling, lacking a fixed centre, and the Indian novel must be the same’. Now, through Molina’s essay, and through Ribeyro (Pankaj had only mentioned their last names, and they’d stayed with me), I encountered myself and the alien habitat called the ‘Indian novel’ in other milieus – milieus in which I vaguely knew such tensions had existed, but which were confirmed to me, through the translation, with a new urgency. Through Ribeyro, the great writer of short stories and (as Molina points out) the great notebook- or journal-keeper, I revisited the despair of writers who cannot execute great plans or narratives. Seepersad Naipaul’s despair at never being able to bring his stories to proper fruition; and his son VS’s sense of boredom, later in his own life, with the ‘well-made story’, leading to the writing of The Enigma of Arrival. My own initial sense of futility at not being able to carry out the big tasks, and my love of the short novel and brevity in every literary tradition – a love for which there was probably no term in English.

Did Ribeyro exist? I couldn’t be sure. I had never heard of him, but I’m ignorant of so many things. So wonderful was the position of marginality he occupied in Latin American literature that he could have been a critical concept or invention that Molina (who probably did exist) had come up with. Ribeyro, the man who had pursued fragmentary forms while his contemporaries created monumental works and became ‘global writers’, seemed too necessary and revelatory to be real. Only a fictional character or an idea could be so compelling, so felicitously right.

I recalled a conversation I’d had, by coincidence, with Pankaj when he visited me once in Cambridge in 1998. As we’d walked down alleys past colleges, I’d said that ‘if Rushdie hadn’t existed, the postcolonialists would have invented him’, which was greeted by a roar of laughter. (A month ago, a historian said the same thing to me. When I pointed out that I’d had the thought before, she asked me if I’d written and published it somewhere, and if she might have picked it up unconsciously – but I don’t think I have.) This is not a cavil against Rushdie, whose work I have taken pleasure in. My remark emerged from the fact that I found it possible to speak to students about Midnight’s Children – one of my responsibilities in Cambridge, where I was writing a book, was to teach a course on international literature – without having really read it. I wasn’t teaching them Midnight’s Children, of which I’d probably read to page 60 – but the novel would come up in the way landmarks do, and I found that it had reached, in postcolonialist vocabulary, a level of abstraction where one could hold forth fluently on it – as one might on an idea – without needing to really encounter its specificity. Later, when I resumed reading it, I discovered many details and characteristics in it that I thought original and enlivening. But postcolonialism, ‘India’, and the ‘global novel’ had made this materiality abstract, so that different paragraphs could be quoted from the book with the same commentary for each: ‘Notice the hybridity; the polyphony; the chutnification and admixture of Indian and English words… English, or “Hinglish”, is now an Indian language’. It is as if the actual paragraphs or sentences themselves didn’t exist in their particularity.

If the postcolonialists invented Rushdie – and not, you noticed after the triumphal rhetoric ebbed, an especially interesting one – because they needed a Rushdie, the anti-postcolonialists must have had their inventions too. One of these is Pierre Menard, about whom the one eponymous essay that exists begins: ‘The visible work left by this novelist is easily and briefly enumerated’. The tone of the sentence and the slightly dismissive emphasis on ‘visible’ suggests that to judge a writer by their work (which would imply that the greater its enormity and volume the more its significance) is too easy a task; and this comprises a useful starting-point for the anti-postcolonialist and anti-globalist, who are arguing for the indispensability of in- or semi-visibility. Menard’s major unfinished work comprises fragments of Don Quixote: ‘He did not want to compose another Quixote – which is easy – but the Quixote itself’. This dismissal, and redefinition, of the ‘easy’ is continued in the essayist’s account of the strategies Menard tried out when embarking on his project: ‘The first method he conceived was relatively simple. Know Spanish well, recover the Catholic faith, fight against the Moors or the Turk, forget the history of Europe between the years 1602 and 1918, be Miguel de Cervantes. Pierre Menard studied this procedure (I know he attained a fairly accurate command of seventeenth-century Spanish) but discarded it as too easy.’ In contrast to postcolonial readings of paragraphs in Midnight’s Children, where each one satisfies certain necessary prerequisites and ends up being the more or less the same as the other – that is, the paragraph becomes an abstraction – the essayist writing about Menard makes an anti-postcolonialist comparison of paragraphs from Cervantes and Menard to draw our attention to radical differences:

It is a revelation to compare Menard’s Don Quixote with Cervantes’s. The latter, for example, wrote (part one, chapter nine):

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counsellor.

Written in the seventeenth century, written by the ‘lay genius’ Cervantes, this enumeration is a mere rhetorical praise of history. Menard, on the other writes:

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counsellor.

History, the mother of truth: the idea is astounding. Menard, a contemporary of William James, does not define history as inquiry into reality but as its origin…

The contrast in style is also vivid. The archaic style of Menard – quite foreign, after all – suffers from a certain affectation. Not so that of his forerunner, who handles with ease the current Spanish of his time.

*

Ribeyro, in a sense, is – in Molina’s essay and Pankaj’s translation – the latest invention that anti-postcolonialists have thrown up in order to alter the terms of the discussion. For now, it doesn’t matter if he exists. Coming into contact with him has created an opening.

Note: the word ‘anti-postcolonialist’ has no existence outside this story.