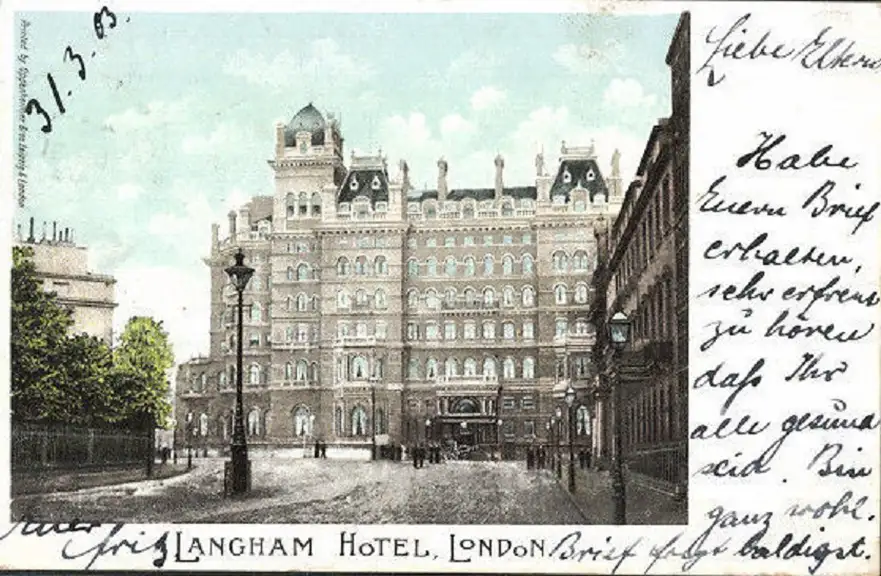

Postcard, 1903, with a picture of the Langham Hotel, London, where, in 1955, Naipaul wrote the first story of Miguel Street in the BBC freelancers’ room. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Leaving the Naipaul Myth Alone: On Sanjay Krishnan’s V.S. Naipaul’s Journeys

Vineet Gill

V.S. Naipaul was fond of repeating himself. We have heard him speak in his characteristic way, in recordings or at live events: the long pauses and the multiple stabs for emphasis at the same word or phrase. ‘Yes, yes, yes . . . yes.’ ‘Splendid, splendid,’ he says at the end of a poetry recitation at a university in Uganda, as recorded in Paul Theroux’s Sir Vidia’s Shadow. And then, a little later, he reveals his true feelings about the poems directly to Theroux: ‘Dreadful, dreadful.’

More than just a mannerism of speech, Naipaul’s penchant for repetition informed much of his writing. His books are concerned with the same set of lifelong preoccupations: unlikely journeys, unachievable ambitions, personal and collective failures, half-formed and broken societies. The people, situations, and settings of old books are revisited in new ones, old memories are relived. Such recurrences shaped everything he wrote. And connected to these, indeed at their very centre, is his persistent inquiry, of necessity autobiographical, into how a writer is formed.

No other writer has dramatised the writing process, its struggles and epiphanies, with more fertile self-reflexivity than Naipaul: the subject of his writing is often writing itself. The freelancers’ room in a BBC building in London, the ‘non-rustle’ script paper, the hopeless dreamer doubled up over the typewriter in a ‘monkey crouch’, the many false starts on the page and the writer’s true voice presenting itself as ‘my first publishable sentence’, like a divine revelation—such details have also become part of the Naipaul mythology. And the drama of this creative coming-of-age is repeated multiple times, retaining its freshness in every iteration, in books spread out over several decades: Finding the Centre, The Enigma of Arrival, A Writer’s People, to name three.

Naipaul understood that the difficulties and failures inherent to writing are not meant to be overcome; they are to be accepted, as one accepts a chronic health condition. But Naipaul was all too aware that the fate that awaited most writers was that of unmitigated failure, unaccompanied even by minor achievements, and it was this kind of absolute failure that captured his imagination. He portrayed the failed writer as a romantic hero with comic overtones. This figure appears often in Naipaul’s books. Consider, for instance, the protagonist of A House for Mr Biswas (based on the author’s father, Seeparsad Naipaul), who, shortly before his death, writes, in a letter to his son: ‘I am beginning to feel that I could have been a writer.’

Another literary failure appears in the late novel Half a Life: Willie Chandran, who looks at a couple of negative notices of his first, and last, book of stories and says to himself, ‘I will write no more.’ Then there is the almost-failure of Naipaul himself, who tells us that he survived as a writer only because of random good luck and supportive publishers: ‘Without them I would have languished; perhaps never got started.’ While his father died with the regret that he could have been a writer, V.S. Naipaul was always haunted by the feeling that he could have been a failure.

In his days of innocence in Port of Spain and 1950s England, Naipaul wanted to be a particular kind of English metropolitan writer—someone like, say, Somerset Maugham—a self-assured inheritor of the whole of the Western literary tradition. It took him a lot of time and labour to figure out that he would never be able to realise that dream, tied as he was to his own unique experiences and limitations. So his future success was determined by his early acceptance of this definitive failure, which enabled him to uncover basic truths about himself. It enabled him, most of all, to end the double deceit he had created for himself in his apprentice years, defined in The Enigma of Arrival thus:‘I was hiding my experience from myself; hiding myself from my experience.’

Learning to write was a project of self-rediscovery for Naipaul. In fact, learning and writing were indistinguishable from each other. ‘To write was to learn,’ he says in ‘A Prologue to an Autobiography’. One thing he had to learn was that his ‘material’ (as he referred to it) was inside him, and that he had to honestly engage with his memories and experiences to get to it. Yet mere engagement wasn’t enough for Naipaul. He set himself the daunting and radically original task of re-evaluating that material in book after book, by holding up to scrutiny not just his past but also the complicated history it had emerged from. The past was not a foreign country for Naipaul; it was a whole world, a multitude of interconnected worlds, and it became his task as a writer to inhabit these worlds, to try and make sense of them and, most importantly, to keep returning to them. ‘I defined myself,’ Naipaul says in Enigma, ‘and saw that my subject was not my sensibility, my inward development, but the worlds I contained within myself, the worlds I lived in.’ (This word, ‘world’, was important to Naipaul. It appears often in his books, sometimes in their titles. ‘The world is what it is . . .’ begins the opening sentence of A Bend in the River.)

In Sanjay Krishnan’s excellent study of Naipaul’s work, V.S. Naipaul’s Journeys, we follow two parallel but counter-directional trajectories: that of the writer’s life—‘from periphery to centre’, as the book’s subtitle has it—and that of the work—which took the writer back from the imperial centre of the world to the peripheral societies that he was perpetually drawn to. ‘To become a writer, that noble thing, I had thought it necessary to leave,’ Naipaul wrote in Finding the Centre. ‘Actually to write it was necessary to go back.’

Krishnan’s book gives us a sense of what that going-back actually entailed and how it shaped the writer’s imagination. ‘Naipaul was one of the first postcolonial writers to think about global parallels between different groups of unprotected and exploited peoples,’ Krishnan writes. The term ‘global’ has a very different ring in this context, and in a sense it undermines the simplifying and homogenising tendency of globalisation, which aims to reconfigure the world as one big marketplace teeming with insatiable citizen-consumers who all look alike and have the same desires. The underclass we encounter in Naipaul’s books—the Indian indentured labourers in the Caribbean (Naipaul’s ancestors), the migrant workers in England, the rebellious tribals in Mozambique—comprises a diverse set unified by one overarching predicament: they are all victims of the global forces that threaten to uproot or even eradicate them. It’s them against the world.

The writer has to deal in particularities. Not for him the sociologist’s privileges of looking at the big picture and making useful generalisations. Regardless of the scope of his project, Naipaul’s focus was always on the individual, to the extent that in some of his late non-fiction the author himself seems to retreat to the background, allowing his characters to take over the narrative through reams of long quotations. These individual stories were of such great interest to Naipaul that he often returned to them years later. For instance, he first met, and wrote about, a man named Imaduddin in Indonesia in 1979, for his book Among the Believers; and then, in the 1990s, while working on its sequel, Beyond Belief, he sought out Imaduddin once again, to see in what ways he had, or hadn’t, changed. ‘Such an investment in individuals and how they have developed,’ Krishnan writes, ‘constitutes an important part of Naipaul’s effort to make visible how his own evolving understanding of his formation can be brought into conversation with the way others reflect on their pasts.’ He undertook a similar journey to a different country in the 1980s, with the objective of once again meeting a man who went by the nickname Bogart. Naipaul had known Bogart in his childhood and had written about him in the 1950s, sitting in that freelancers’ room in London. His ‘first publishable sentence’ was part of a story entitled ‘Bogart’.

Kierkegaard called repetition the only source of beauty in life and art. And Naipaul’s writing, with its musical tendency to revive old themes, may be the closest corroboration we have in literature of that aesthetic idea. But this is not to say that Naipaul didn’t value or care about newness. He was obsessed with questions of form, and the greater part of his struggle as a writer had to do with finding the right form for a work-in-progress. The critic James Wood once interviewed him for a piece, and this was Naipaul’s condescending yet valuable advice to him: ‘If you want to write serious books, you must be ready to break the forms, break the forms.’ Naipaul’s anxieties about form, and his deep understanding of it, took him away from the novel in the late 1960s, at a time when the novel was establishing its dominance over the literary cultures of the West. When gifted essayists like Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal were getting increasingly disaffected with non-fiction and dreaming of producing the Great American Novel, Naipaul was beginning to lose faith in the artifice and one-dimensionality of fiction, and inventing his own brand of ‘high journalism’ (this was before the term ‘New Journalism’ became a buzzword in America).

In any case, the realist European novel was of little use to Naipaul. He believed that he didn’t possess the ‘larger self-knowledge’ that was expected of the novelist. What he ended up doing, then, was to break the form, by pushing the limits of the conventional novel, and allowing it to become an engagement with other kinds of writing: memoir, history, journalism. Another important mode of departure from the novel for him was travel writing, which he regarded as an end in itself as well as a means to revitalise his fictional imagination. In his search ‘for a new kind of book . . . a new way of travelling’, Naipaul took up the task of educating himself better about the places and lives he felt a connection with. Which was why he felt the need to write sequels to his books about the Islamic world, and why he ended up writing not one but three books about India. Repetition again.

Krishnan calls India: A Million Mutinies Now—the last of the India triptych—Naipaul’s ‘biggest and most ambitious work of travel writing’. The polemical fierceness of his first India book, An Area of Darkness, gives way here to a more sympathetic tone. This is the sympathy, the negative capability, of the novelist—an openness to views and opinions contrary to one’s own. ‘Naipaul is interested in the complex selves he encounters,’ Krishnan writes, ‘treating them with the eye of a novelist who is interested in telling stories that are irreducibly “heteroglossic,” where the individual is not simply made to stand in for one ideological standpoint.’

This was a far cry from his first travel book, The Middle Passage (1962), which earned him the notoriety that dogged him throughout his life. His hard-edged portrayals of Trinidadian Blacks in that book were noted and criticised for their casual racism. Krishnan quotes one of the offending passages at length, about ‘a very tall and ill-made Negro’ spitting from a train window. ‘His face was grotesque,’ Naipaul writes. ‘It seemed to have been smashed in from one cheek.’ And when his eyes meet the author’s, there’s no human contact between the two men—only trepidation on one side and what Naipaul perceives to be ‘malevolence’ on the other. ‘This man, whose appearance suggests that he may well have been a victim of violence, is transformed into a placeholder for the mob,’ Krishnan writes.

If the passage quoted above fails to move us or even make us laugh—which might have been the intention of the author—it is not only because its disgust fails to excite us in any way, but also because it fails to meet the standards of subtlety and attentiveness Naipaul has achieved elsewhere in what’s loosely termed ‘description’. Krishnan blames Naipaul’s ‘racialised’ upbringing in the Caribbean for this and other blind spots. Naipaul grew up in an Indian ghetto in Trinidad, in a tradition of jokes and stereotypes and ‘mutually belittling talk’, in Krishnan’s words, and he brought those influences into his writing, for better or worse. Krishnan writes:

[What] is uniquely compelling about Naipaul’s work is its refusal to falsify the historicity by which it is produced. Naipaul does not uncritically accept the cultural prejudices or reflexive assumptions of his past, but seeks, by making that past visible through aesthetic staging, to present it as an objective condition that needs to be worked through.

Naipaul’s realism was about making the writer’s present, and the writer’s past, fully visible to the reader, through a kind of plain speaking and unflinching attention to detail that might be disconcerting for some. Krishnan quotes a passage from An Area of Darkness, about sweepers in a Delhi café, which at once defamiliarises a mundane reality—‘they will squat and move like crabs between the feet of the customers’—and offers a powerful bit of social commentary on the Indian class system. It gives us a sickening insight into the choreographed, performative nature of social oppression: ‘They are not required to clean,’ Naipaul writes.‘That is a subsidiary part of their function, which is to be sweepers, degraded beings, to go through the motions of degradation.’

An Area of Darkness was attacked by many, especially in India, as a superficial, temperamental, and dismissive take by a traveller who was looking at the country through a Westerner’s eye. In his review of the book, the poet Nissim Ezekiel took issue with Naipaul’s ‘aloof, sullen, aggressive manner’ of exploring his subject. Ezekiel wrote that Naipaul was seeing the India he wanted to see—a place characterised by its surplus of filth and poverty, a doomed postcolonial society riven by corruption and anomie. Ezekiel was right to an extent: the author’s ‘self-chosen situations of extreme anguish’ provided him with the meat of the narrative. But this was far from the anti-India book it came to be regarded as. Krishnan draws our attention to the ‘style of critical thinking’ that Area encapsulates and the tone it employs. He says that the book is ‘focused less on expressions of solidarity and sympathy . . . than on establishing a standpoint from which to articulate resistance to an unsatisfactory state of affairs’.

One is tempted to read V.S. Naipaul’s Journeys as an apologia of sorts, even though Krishnan makes it clear right at the outset that he does not intend to mount a defence for the great but misunderstood writer. He distances himself from the discourse of defence/attack in the context of literature, because such a discourse can’t look beyond reputations, to be demolished or restored. There’s no room in it for any real critical engagement with the only legacy a writer can leave behind: a textual record, a body of work. Krishnan says that both Naipaul’s detractors and admirers have been influenced, in one way or another, by the ‘Naipaul myth’: shaped as much by the writer’s own provocative public statements as by the various misreadings of his books. And as Naipaul himself reminds us in his essay on Conrad, writers’ myths invariably end up superseding and undermining the work.

Krishnan aims to go beyond that myth through ‘contextualised close readings’ of Naipaul’s books. He divides the oeuvre into three main segments: ‘Early Writings’, ‘The Middle Period’ and ‘Late Works’. Each chapter of V.S. Naipaul’s Journeys is devoted to two or three books, and each work is read not in isolation but in the light of what preceded and followed it. One of Krishan’s critical objectives is to understand how Naipaul changed as a writer from one book to the next. Krishan’s comparative analysis is fascinating, painting for us a portrait of a very different Naipaul, someone who was always reviewing his stand and trying to correct it. For example, Krishnan says that ‘An Area of Darkness is a more internally divided work than A Middle Passage’. He notes the ‘shift in tone and sensibility’ looking at a relatively uptight essay from 1974 and comparing it to the ‘disarmingly intimate’ Finding the Centre, published in 1984. He contrasts the flawed comedy of A Middle Passage with the ‘feeling of quiet solidarity’ with marginal lives expressed in The Enigma of Arrival.

For all the careful attention given to the work, there aren’t many clues in Krishnan’s book about Naipaul’s literary education. And Naipaul is more to blame here than Krishnan. We are once again face to face with the Naipaul myth. Was he really the ex nihilo genius that he wanted us to think of him as, someone who had transcended the question of influence? Or was he simply good at covering his tracks as a reader and critic? Naipaul regularly wrote critical essays and reviews. He was well acquainted with the works of writers as varied as R.K. Narayan, U.R. Ananathamurthy, Anthony Powell, Conrad, Proust and Montaigne. He read constantly and carefully, with the perceptiveness of a writer on the lookout for inspiration. He has been compared to Dickens and Orwell, both very different writers, and both publicly ridiculed by Naipaul. (‘Dickens died from self-parody,’ he once said.) So where was he learning from? We know that the ancients were dear to him: Martial, Marcus Aurelius (Mr Biswas’s favourite writer). Krishnan tells us that Naipaul translated a sixteenth-century Spanish novel, Lazarillo De Tormes, into English when he was a student at Oxford, and that Miguel Street was modelled on this episodic narrative. The detail offers a rare insight into the working of a complex literary imagination that was also multilingual, a term we don’t usually associate with Naipaul for some reason.

Throughout his survey of Naipaul’s work, Krishnan manages to keep the details of his subject’s life at arm’s length, except when these details have a direct bearing on the writing. He refers the biographically inclined reader to Patrick French’s The World Is What It Is, a warts-and-all portrait that added a new dash of scandal to the Naipaul myth. But it’s wrong to regard French’s biography merely as evidence for the prosecution. French was well aware of Naipaul’s worth as a writer, as Krishnan reminds us here, and wanted the work to be assessed ‘on its own terms’.

The kind of level-headed, disinterested reading that Patrick French was appealing for, and Krishnan demonstrates in his book, has become rare these days. In December 2022, the New York Review of Books published an essay on ABend in the River. It is by Howard W. French, a professor at Columbia University, and it levels the old charge of racism against Naipaul. At one point, Howard French says that the novel’s protagonist, Salim, was only a medium used by Naipaul to ventriloquise his own prejudices and resentments against Africans. Krishnan wrote a letter to the NYRB in response to the essay, pointing out ‘French’s inattention to the novel’s use of irony’ and ‘the crucial fact that Salim is an unreliable narrator whose moral and practical failings are cruelly exposed in the concluding chapters’. Howard French countered Krishnan with a dismissive letter, offering this absurd justification for his stand against the novel: ‘. . . I have read the novel many times over . . . I have read everything in Naipaul’s oeuvre that touches upon Africa.’

The obduracy and outrage that Howard French expresses, both in his essay and in his letter to Krishnan, have become common cultural currency in our time, from media to academe. The postcolonial and feminist endeavours to expand the Western canon are being replaced, alas, by the project of sanitising it. And so, the critical consensus about Naipaul’s contribution to literature can be legitimately challenged not on literary but on moral grounds. Indeed, literature itself is of little relevance here, since we have once again lapsed into the kind of discourse where there’s no room for books, but always enough for writers, to be defended or attacked, celebrated or ‘cancelled’.

In the second paragraph of his introduction to the book, Krishnan tells us that Naipaul is the only ‘Nobel laureate of non-European origin whose work is excluded from the most recent edition of the widely used Norton Anthology of World Literature’. It’s possible that, in the next few years, Naipaul will be further marginalised on the literary landscape—once again coming full circle, pushed from the centre to the periphery of culture. He may turn into an oddball curiosity in the hall of fame of Nobel laureates, to be encountered only in museums or on Internet quizzes—a literary eminence without a readership. If such a scenario were to come to pass, what do we stand to lose? Krishnan’s book can be read as an attempt to answer that question. And the answer seems to be linked to all those ‘worlds’ that Naipaul contained within himself, and that he captured and recreated in his books—the worlds that are surely too valuable to be allowed to disappear if we wish to better understand the world we inhabit.

Vineet Gill is the copy lead at Penguin Random House India and the author of Here and Hereafter: Nirmal Verma’s Life in Literature.