‘Calcutta is a Great Gallery’: chaloman shilpa andolan, or The Dynamic Art Movement

Ashit Paul

Text translated from Bengali by Rohitashwa Sarkar and Amit Chaudhuri

Episode 1 | Episode 2 | Episode 3 | Episode 4 | Episode 5 | Episode 6 | Episode 7 | Episode 8 | Episode 9 | Episode 10 | Episode 11 | Episode 12

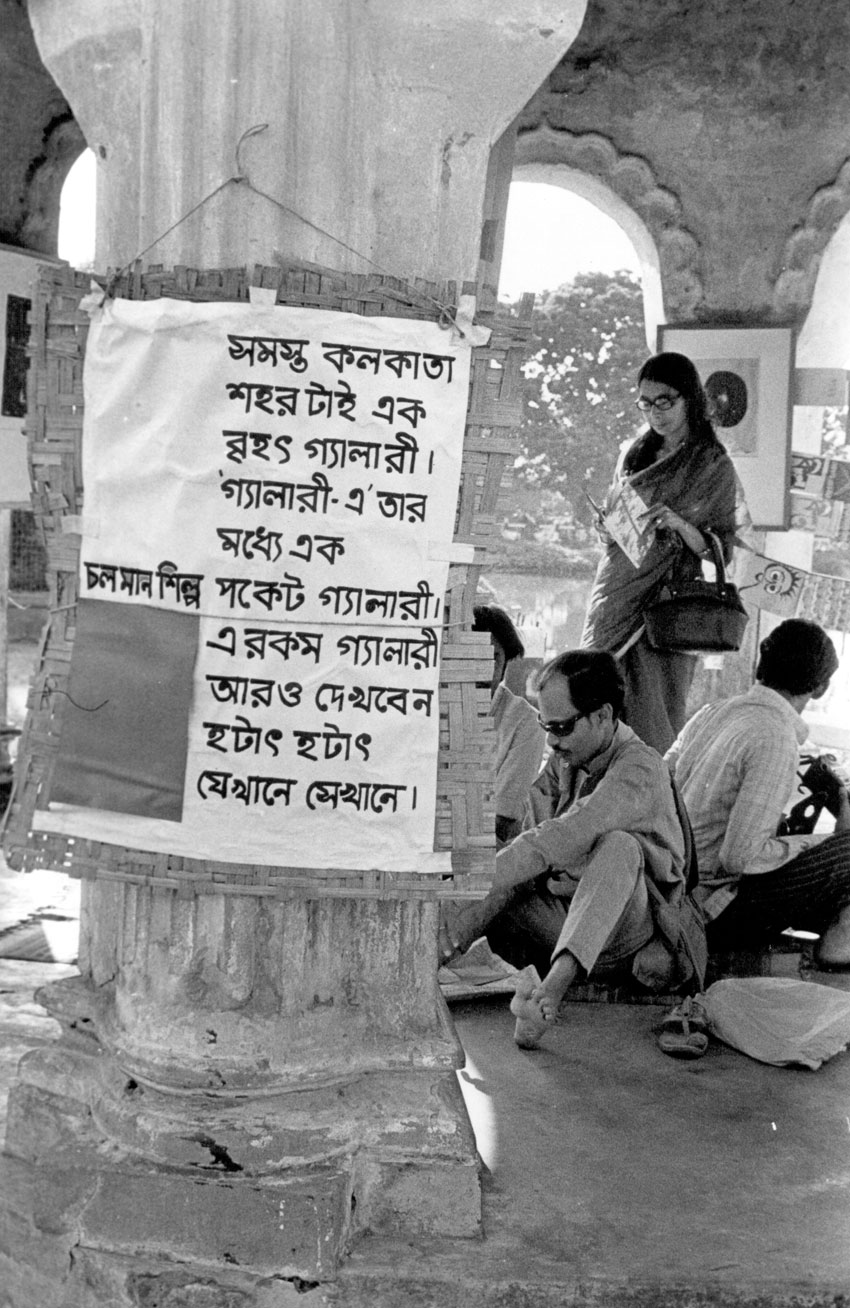

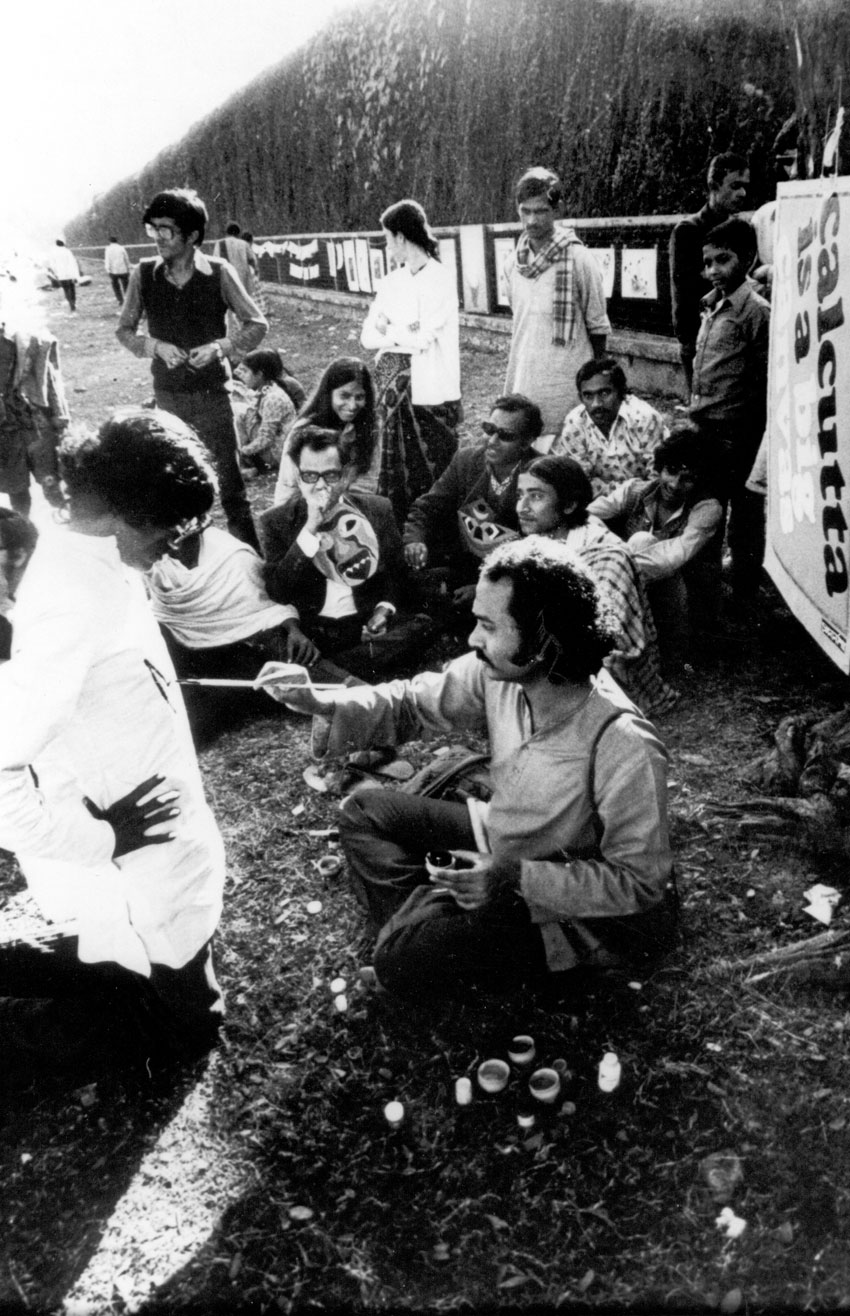

Editor’s note: I saw first saw Ashit Paul’s black and white photographs of the Dynamic Art Movement on Facebook in May this year. We weren’t connected on Facebook; but Gautam Chakrabarty, journalist at the Bengali daily Anandabazar Patrika, who is in my Facebook network, had shared Paul’s post. Social media is indispensable to one of our fiercest contemporary preoccupations – punishing ourselves – but I found myself immediately uplifted by the photos, which, I discovered, comprised the sixth episode in an ongoing commentary about a movement Paul had initiated in 1975 in Calcutta. I was particularly struck by the text of a poster that appears in photo 7 of Episode 6 below: ‘All of Calcutta is a great gallery. Gallery A is, in its midst, a pocket gallery. You’ll run into more galleries from time to time, here and there.’

The actual movement – chaloman shilpa andolan – had a life of roughly three years. (The word ‘chaloman’ means ‘on the move’ or ‘moving’; the word Paul uses for it in English is ‘dynamic’.) Calcutta still was a city, then, of transformative, quixotic projects – in politics; in the arts – a city of manifestos and taking sides (of these, only the last-mentioned characteristic survives), and the photos were engrossing because they seemed to capture one of the last notable instances of the sort of imaginative and conceptual play I’d associated Calcutta with from childhood onwards. The other remarkable thing was the fact that I knew so little about Paul (though I’d once seen a book he’d edited, on Bengali woodcuts) and nothing about this movement. Sadly, I don’t think I’m alone in this, even in Calcutta.

Both the photos and Paul’s texts reveal, episode by episode, how a movement might happen: the prehistory of dissatisfaction; the beginnings of an idea; the unlikely circumstances and cast of characters; its deliberate self-distancing – so difficult for us to comprehend today – from political power and money. Naturally, it’s the kind of project that’s of interest to this website, which is also a place for recalling, and recording, alternatives to our world of festivals and biennales. Of course, the movement has a context in Bengal and outside it: Tagore’s use of open spaces for pedagogy and performance in his Visva-Bharati University; Benode Behari Mukherjee’s frescoes on the ceilings and walls of houses in the Visva-Bharati campus; the wall paintings on houses in rural North India; the intricate alpana patterns made by Bengali women on floors during festivities; the revival of the folk ‘jatra’ form by theatre directors in Calcutta in the 1960s for political purposes and to dismantle the proscenium; the transposition of Richard Wagner’s Gesamkunstwerk or ‘total artwork’ to the German art world, especially in Josef Beuy’s experiments with ‘social sculpture’, roughly contemporaneous with Paul’s project.

But Paul is unique in his time for his approach to the city’s surfaces as canvas. His is one of the last key campaigns before free market globalisation made alternative art movements impossible – not by suppressing them, but by appropriating their language. Paul’s decision, to retrieve some of the chaloman shilpa andolan’s moments about four decades after it ended, is important. As a pioneer of public art – not only in Calcutta or India, but anywhere – he is a thinker who responded uniquely to the obstacles and exuberance created by pre-globalisation urban modernity. For him, Calcutta (its spaces, buildings, machines, and its human and animal population) was the main creator: both gallery and, to a large extent, exhibit.

*

Foreword: Episode 1

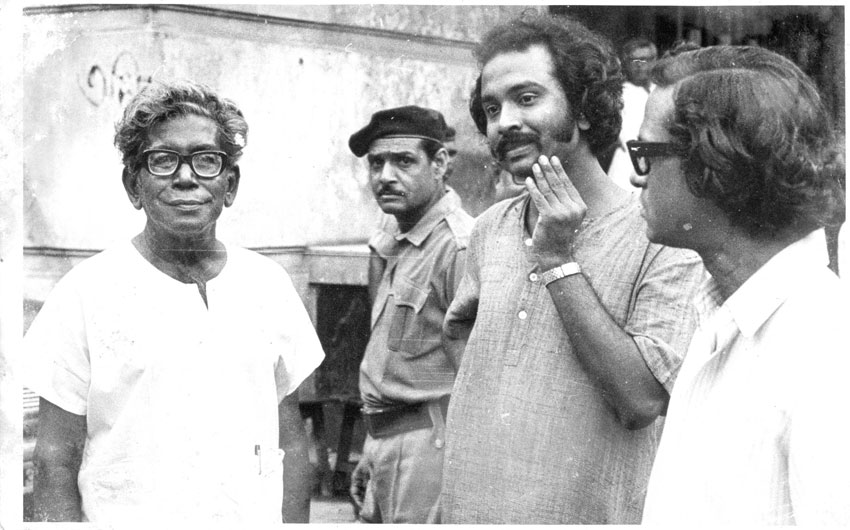

Ramkinkar Baij (left), Purnendu Pattrea (right) and Ashit Paul (centre); security guard in background; May 1975

Sounak Lahiri died recently, prematurely. Many people have mentioned him in relationship to the chaloman shilpa andolan. I, too, have been asked to write about the movement and the period in which it happened. After giving this much thought, I’m putting down a few points which I intend to explore further in some notes.

The year was 1970 – the Naxalite movement was ebbing in Calcutta. I left my home in College Street for Tripura: a kind of exile. At that point, there were people in Tripura who were involved in the independence struggle for Bangladesh. I soon got mixed up with them, exhibited my art, started writing for journals. No one in Calcutta had a clue about my whereabouts. My art-college mood possessed me: time and again I felt the irresistible upsurge of ‘the 70s is the decade of freedom!’ adage in my soul – but to what avail? I returned to Calcutta after several months in Tripura. I stayed in new homes. I published the English-language journal Artist and was completely immersed in the task. In the confines of these strange new homes I worked away. I spent several months in an unfinished room on the roof of the municipal corporation. There were incredible experiences – I got a job with Anandabazar Patrika at Purnendu Pattrea’s invitation. In 1974 I went to Australia and did an exhibition – I got acquainted there with Sibnarayan Ray. How full of intelligence he was, and what a dreamer! His presence enlivened me at every moment. He acted as though our difference in age was irrelevant. Once I got back from Australia, I returned to my earlier workplace. Ahi da (Ahibhushan Malik) was thrilled to hear that the exhibition had been a success – as was Purnendu da. I proposed to Purnendu da one day the idea of doing something big in Calcutta, because no one thinks about artists, and because the lack of awareness about art meant galleries continued to remain empty. Purnendu da responded sceptically. He thought it would be hard to find people here for that kind of thing. But there’s no harm in trying, he said.

One evening, I went to see Lady (Lady Ranu Mukherjee, with whom I had developed a close friendship at The Academy of Fine Arts during my art college days). She listened carefully to the stories of my travels, and said she would arrange a seminar for me, where I could make a presentation with slides. She put together everything once I agreed. I displayed several pictures on my newly-bought projector, and then asked, ‘Why is a consciousness regarding art not developing in the common people of our city?’ I hadn’t noticed a gentleman in saffron at the back, who asked, ‘Have you found out if our artists themselves have developed this consciousness?’ On hearing the question, I became a little silent because Lady was sitting right in front of me. I said, ‘You’re absolutely right. No point in blaming common people if artists themselves haven’t attained a degree of awareness!’ Upon the close of my lecture, as the lights came back on, the first thing I wanted to do was seek out the gentleman who’d asked the question. To my surprise, it was Subho Thakur. His face was covered in a white beard and moustache, and he was wearing a loose saffron robe. This was the notorious blue-blooded rebel-artist and collector of the Thakurbari. He had edited Sundaram , which had stunned and inspired me. I told him, ‘You’ve hit the nail on the head.’ He was a man of few words; he thumped my back and said, ‘You people are young, see if something can be done – everybody seems to be going around without vision or purpose’. These words had an impact on me. I stored them inside.

Soon Purnendu da informed me that Ramkinkar [editor’s note: Ramkinkar Baij, sculptor and artist, a major figure in Tagore’s Visva-Bharati university] would be here soon; he was going to go around Calcutta talking about sculpture. He’d be staying at a nearby hotel – so, if I wanted to, I could go and meet him. I couldn’t wait to. He arrived in a couple of days and we went to meet him in the evening. I was prepared with pen and paper and ink – whatever was close at hand.

He was seated on the white bed of the second-floor room in his hotel, wearing a white kurta and lungi – you’d have thought he was a monk. He warmed to us quickly during that first meeting, and we talked for quite a while over beer, although he preferred desi liquor. But no one had brought desi liquor to the meeting. I kept sketching him on a piece of a paper, and upon Purnendu da’s request he started singing in an open-throated voice and it seemed like God was singing; then he took some paper from me to make some portraits of me. He signed on my sketches too. Purnendu da tried to encourage Ramkinkar to talk about controversial things related to Nandalal [Nandalal Bose: one of the most prominent artist-teachers at Visva-Bharati], but he was evasive. He knew how to overlook various kinds of disappointment. Urban shrewdness had failed to vanquish rural naivety. There had been a lot of fuss about his statue of Rabindranath, he said; only Tagore himself appreciated the work. That Calcutta doesn’t have any of Ramkinkar’s works is a cause of sorrow, shame, and regret. But he had no regrets. He had begun to look upon life with a kind of ease. I went to his house in Santiniketan later, took pictures, put together exhibits of his work; I saw how, while he lived under his canopy made of hay, his ordinary life was borne aloft by his extraordinary mind. I saw how his oil paintings obstructed and absorbed the water when rain trickled through the hayshed. He had no misgivings when that happened. This was the authentic artist-of-the-earth. The few days he was in Calcutta we would reflect, during evenings at his place, on global art through songs and conversations.

After I returned from Tripura to Calcutta, a few young people arrived in the city with hopes of being artists – or something even loftier. Among them there was Partha Gangopadhyay, a good table tennis player who decided to seek my tutelage in painting and study at the Art College while living in his aunt’s house. He was very quiet but resolute. I remember he quickly became my friend and companion. Meanwhile, ideas were pullulating inside me at this point.

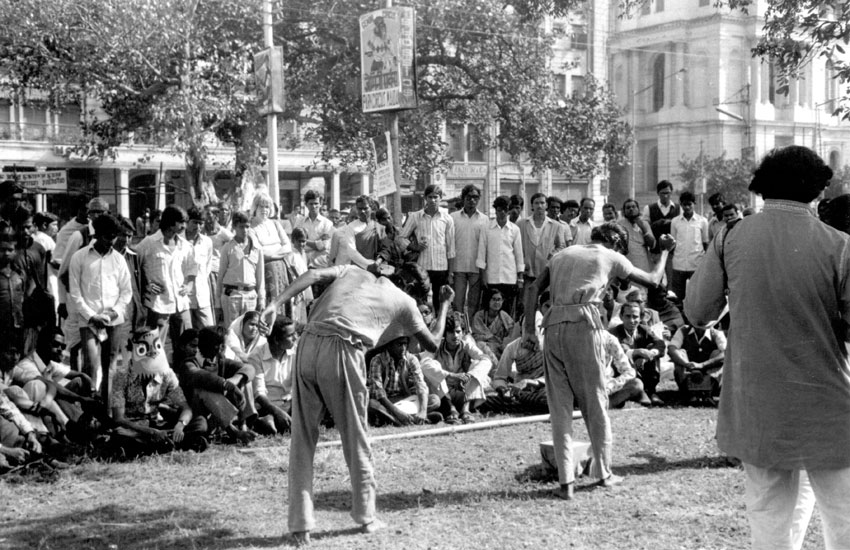

Badal Sircar’s theatre group was called Satabdi. A few days a week, he would conduct a rehearsal in a room above the Academy [The Academy of Fine Arts], and I would go there once or twice a week, meet everyone, maybe put up an exhibition. Suddenly, one day, I saw Badal Sircar doing an enactment of Spartacus on the field opposite the Academy, and a throng of people watching. Because there was no intrusion from vehicles or anything else at the time, it wasn’t hard to watch the play. I too stood and watched all of it as well as the expressions on the audience’s faces, and I thought, This is what we need. Only when theatre enters the space of the people will it reach their emotions. What the stage couldn’t achieve, plain, level ground would. In the Academy, Pratul (Batyabal) babu, Lady’s close and trusted friend, looked after her papers and was her personal confidant too. I asked Pratul babu, Doesn’t Badal babu’s group rehearse anymore in the room upstairs? Pratul Babu replied promptly – There’s been no rent for several months; so he was evicted. I was startled by how easily he explained it to me. The Academy didn’t have the sense to understand that Badal Sircar’s rehearsals at the Academy would enhance its reputation. The event left a mark on me. I was perplexed by why the Academy, a place for art, couldn’t hold on to Badal Sircar.

When I related this story to my friends over tea at Rashbehari More, they were aghast. But Badal babu himself never protested. This was the first move against proscenium theatre. After this, for many years, his group and several others’ regularly performed at Curzon Park. They’d raise money from donations at the end to keep their projects going. We, in the process, got access to plays and actors and actresses whose quality was second to none in the world. I began to taste freedom in our arts. Thoughts gathered in my mind.

*

Episode 2

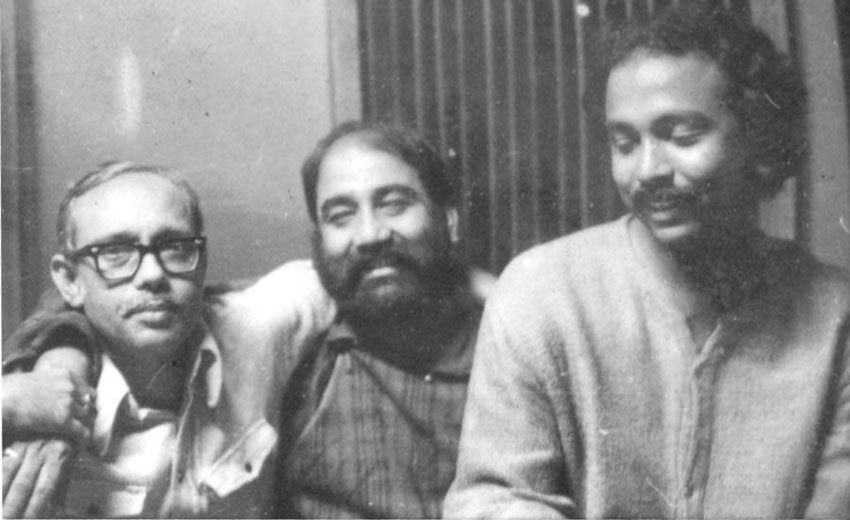

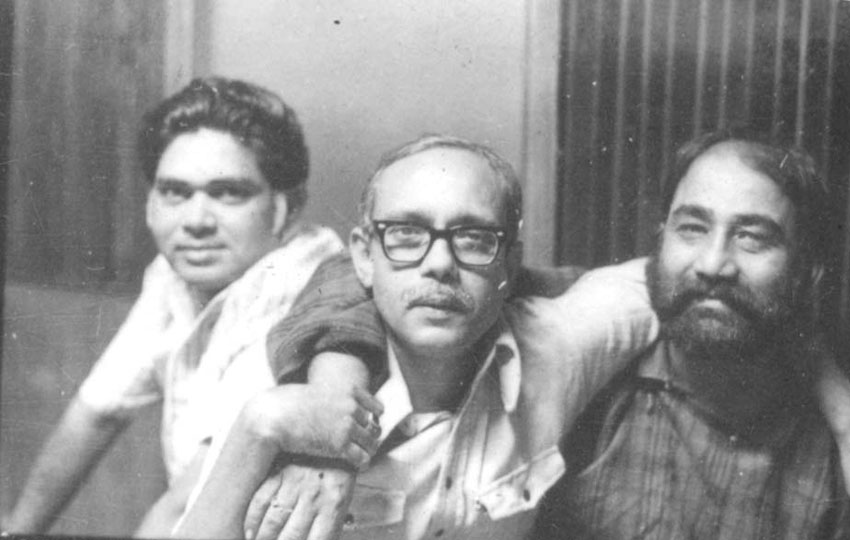

The poet Shakti Chattopadhyay (left), the artist Prakash Karmakar, and Ashit Paul, 1975.

Poet and novelist Sunil Gangopadhay (left), Shakti Chattopadhyay, the artist Prakash Karmakar

At Rashbehari More, Amritayan, which has since been swallowed up by the Metro Rail, was where we gathered for our regular adda. A lot of people went there – Kallol Majumdar, who mainly wrote stories; the young poet Samarendra Das; Dhurjati Chandra, accompanied by other writers of that decade; the musician Timir Baran, to drink tea sometimes, with an English book in his hand which he’d read while sipping tea; Nabarun Bhattacharya. I’d seen the latter’s father, Bijan Bhattacharya, too, a few times.

Kallol used to live in a hostel in Bhowanipore; the building was a lot like a cabin in a ship, and there were small rooms inside created by boarded-up partitions; a fan hung from the middle of two rooms – that was it, besides a common room for dining. Kallol used to encamp amidst all this; his demands were minus zero. His head was filled with dreams. Those dreams found their way into his writings.

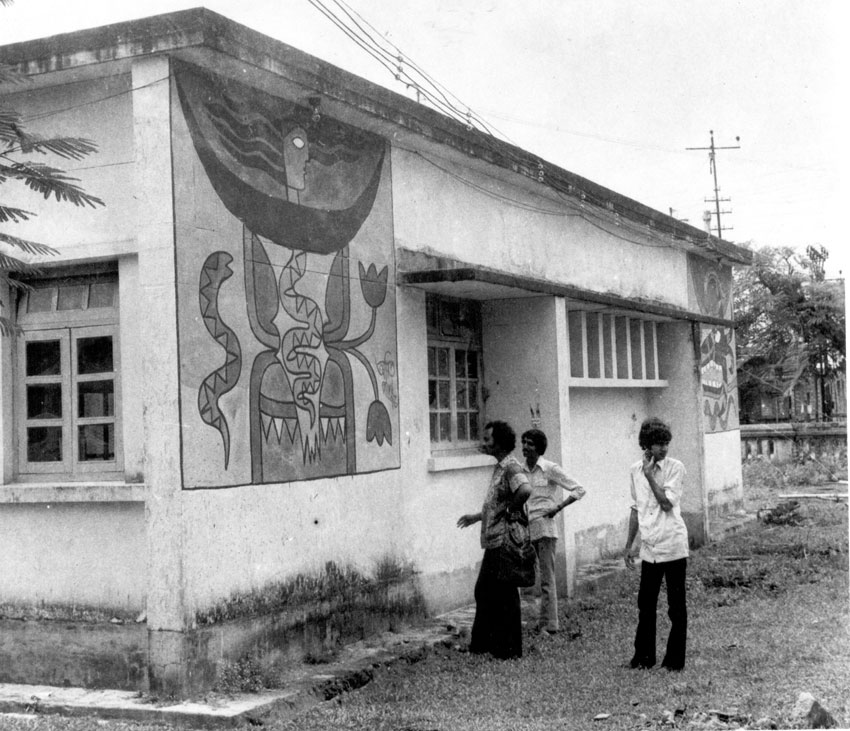

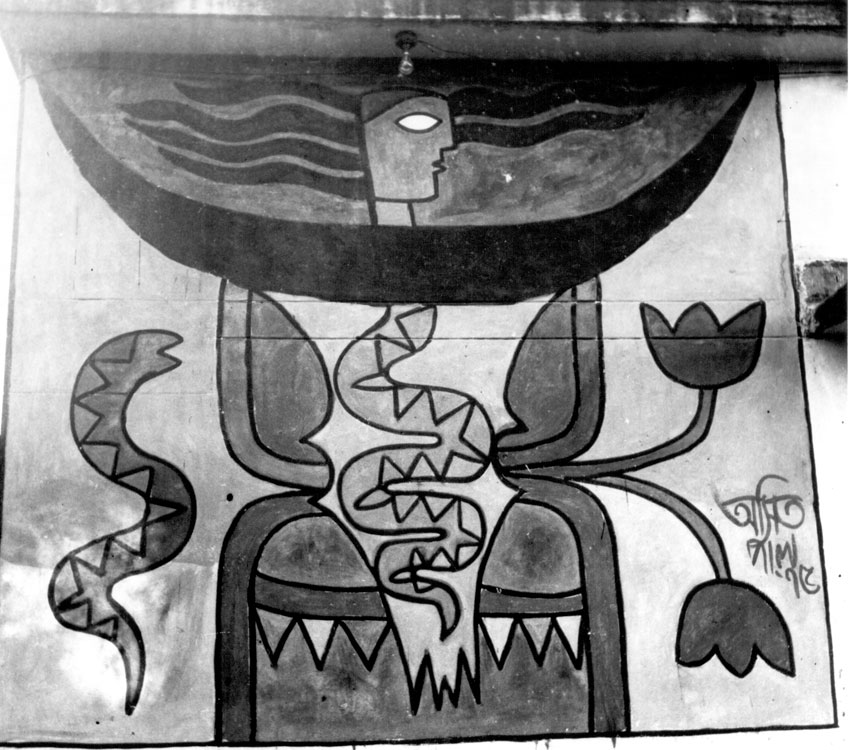

I told Kallol all of a sudden, Hey, if we moved our work out of galleries and magazines, wouldn’t people on the street get to see it? Without giving the question too much thought, Kallol said, Yes, they’ll definitely see it and spit betel juice on it too. I said, Have you noticed one thing – wherever there’s an opportunity for people to answer the call of nature on the roads, beautiful religious pictures are placed strategically to trouble their conscience and deter them. Kallol said, You’re right! I hadn’t thought about it in that way. So we tried, each day, to articulate an idea that had gripped us from within. I’d get on the double-decker bus every day from Ballygunge Depot to go to the office so that I might sit right at the front. That front seat helped me turn many of my dreams to reality. I used to look on all of Calcutta going by. There are wide walls on both the left and the right of the entrance of Chittaranjan Cancer Hospital, and I’d look at them each day from the bus, thinking how wonderful it would be if they had pictures on them.

Everyone had gathered at Amritayan in the evening, and I told Kallol right away that I planned to paint on the walls of the cancer hospital, and that they’d have to write poems and stories on ladders – surely they’d be able to? They knew I was strong-willed – that I’d follow through now that I’d had the idea. I said we could arrange for colours and brushes, but we’d need the permission of the institution first. Kallol said he knew someone there, a leader in the worker’s union at the hospital. Unions mean politics, but Kallol said, Well, this young man is in the Congress Party, but he’s a very nice person. I said, I’d like to meet him tomorrow; is that possible?

Kallol took me to his house the next night; there was a large number of people inside, gathered together – it’s the way political leaders like to live. There was barely an opportunity to speak to the man, and Kallol was of a polite, reticent disposition. He didn’t mind waiting. I, on the other hand, was getting restive in the crowd. However, the man, noticing me, came up to me himself and asked, What kind of problem are you facing – are you having trouble admitting a patient to the hospital? I said, No, I have a different problem. Having said this, I described my plan to him, and he listened intently – it was the first time he’d been approached by the sort of unhinged person I was. His glasses seemed to make his eyes grow even bigger. He said, Wonderful, sounds good, why don’t you paint the pictures – what’s the difficulty? I said, We’re used to political slogans on the wall; now, if we paint pictures on it and they’re erased by your people to make room for slogans again, our entire labour will have gone to waste. The gentleman’s name was Sanjoy Ghosh; he said, You can go ahead – no one will touch your work while I’m here. I asked him to give us a letter clearly stating the hospital’s consent for us to use the premises for art. I also said we would work all night and be grateful if he could make some light available. The wall was grey at the time; I said, I’m sure you realise that pictures won’t come to life on that surface. To this too he said, Don’t worry, you’ll get the letter of consent; just let me know the day before you start work – will it be okay if we give the wall a good shade of white? I said, Yes, white is fine as long as it’s waterproof. He said he’d figure something out. I did a namaskar and left. After badgering him for some days, Kallol came back with the requisite letter. I told him we’d crossed the first hurdle.

I spent some days thinking and listing all the things I needed. Whatever I might go on to do, we’d need, as we began, a manifesto.

I implore houseowners, let your homes become pictorialized; I implore owners of cars, paint on your car’s surfaces to make it enticing. Pictures can be drawn everywhere – even on garbage vans. Bring paintings out into the open from behind closed doors; paintings desire oxygen as much as we do. They won’t be trapped within the four walls of the gallery anymore. Literature won’t remain ghettoed inside books; it will appear in the midst of people; pictures will be drawn on trams and buses everywhere; pictures will run with you, it will be dynamic art; I ask colourists everywhere to step forward, let’s brighten Calcutta! Cows roam around our city; we’ll paint on their bodies too – cows quite like getting tickled. I put down other thoughts and showed it first to Sunil da (the poet Sunil Gangopadhyay); he read it with attention, made a few corrections, and then said, How will you turn such a big idea into reality? I said emphatically that, having thought it up, I’d follow through, and that we’d decided that we’d start at Chittaranjan Hospital. Sunil da simply said that a big change would come if we could pull it off. I had written that literature, art, theatre, music should all gather in one place; they should come in close contact with people in their characteristic forms; each was enmeshed with the other. Sunil da gave us a lot of encouragement that day, and I submitted my manifesto for printing. Once it was printed, I started distributing it to everybody – the counter-current set in motion was full of excitement, and I didn’t worry that no one was clear as yet about what its outcome would be. The age-old paint stores G.C. Laha and Avinash Dutta Company gave me plenty of colours. The owners of both shops were very fond of me.

Partha bubbled with excitement when he heard about what was happening: ‘I’m with you!’ he said. I told him, But that’s not enough, I need many more people.

We decided to keep our brushes and colours in Kallol’s hostel; a ladder was procured, which we kept there too. I took a four-line poem from Shakti da, a short poem from Purnendu da, and everyone else who would come that day was asked to come prepared – a date had been fixed: 4th January, 1975. I had told Sanjay da a few days earlier that we’d work through the night. It was a Saturday, and the cold had set in. I reminded him that the wall would need to be white, and that we’d need lights.

*

Episode 3

That fog-filled winter night, the nighttime adventures

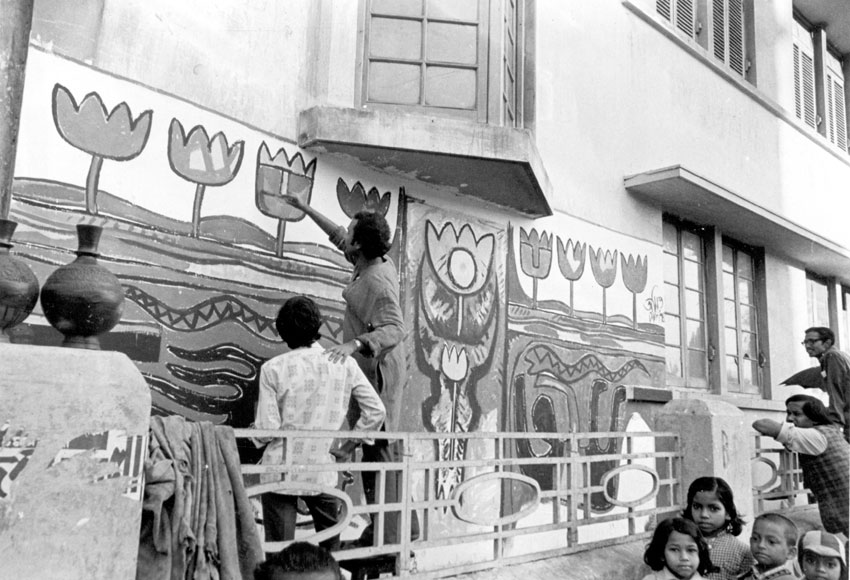

Ashit Paul doing his wall painting, 4th January 1975

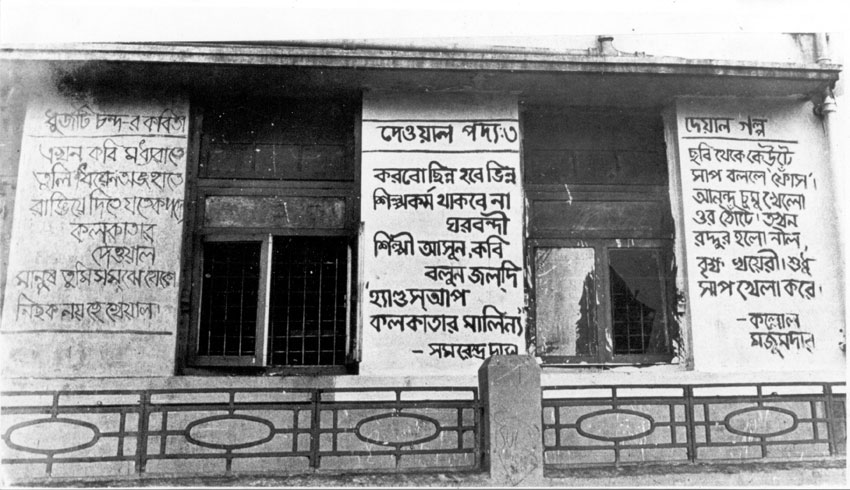

Poetry and excerpts from stories on the wall of the Chittaranjan Cancer Hospital, 4th January 1975

No, we aren’t going to war, but everybody seems to be acting as though they are. 4th January, winter night. Everyone was told to come over to Kallol’s hostel after finishing their dinner. Apart from a couple of people, everybody did. Ashish Chakraborty of Agartala used to stay there then; he had a weak constitution – we used to joke that his dinner in the hostel’s dining room was never-ending. Samarendra Das, Dhurjyoti Chand, Partha Pratim Ganguly, and Kallol all turned up; only the beautiful, slim young Sutanuka Bagchi could not come because she would have had to stay up all night, though it was with us that her thoughts remained that night. Ashish joined us too; our colours and brushes used to be kept at his house at one point. Later, he became even closer to us. Quickly, we mixed colours and made all the other necessary preparations before we began moving towards the hospital, which wasn’t far from the hostel, carrying a ladder on our shoulders. When we reached there we saw that Sanjoy babu had kept the lights on for us. The coat of white had already been applied – I’d noticed it progressing while travelling by bus every day. Admittedly, Kallol had had to persist with Sanjoy da in order to get the job finished. I got to work wearing a large apron that had been given to me by Sibnarayan Ray’s son, and Partha was in charge of the colours. I was working on a huge wall, a wall of a size I’d never worked on before: I didn’t know if I’d be able to complete the painting in a night. As work continued a few pedestrians lingered, but as night wore on the streets became deserted, barring us few madmen who were martyring ourselves for art’s liberation. The poets began to get restive as they waited for their poems and stories to get painted. I assured them while working that I’d personally do their poems for them once I was done with the picture. The cold was getting to everyone. People were trying to keep themselves warm by engaging in various kinds of conversation. Ashutosh College was nearby; a few passing drunks bellowed out asking whether colours and art could cure cancer. Deeper into the night Sanjoy da came to monitor our progress; at that point I had quite a bit left to do, but he didn’t hold back on appreciation. ‘You have stamina! Keep going at it! Let me know if you have any problem – I’ll come and have a look tomorrow.’ Dhurjati Chandra was a poet: his asthma worsened in the cold, and I saw he was suffering. There was nothing at this point. My brush was moving at its own pace, as though someone else was wielding it. Dawn was approaching. There wasn’t a lot of work left, so Partha told me (in East Bengali dialect) to sign my name: ‘Ebar apne soita koira den.’ Before doing so, I descended and considered the picture from a distance, and suddenly noticed a cow going past it in leisurely fashion – I screamed at Partha, asking him to halt the cow, and went running myself. No one had the courage to touch the cow; I, with brush and colours, kept following it and drawing on its body. Regardless of whether anyone else saw the madness of those dream-possessed poets and artists on that winter night, that cow, in its indifference, certainly registered it! I’d forgotten that a photographer had said he’d be there; the first thing he encountered once he arrived was this scene, and set about taking photographs immediately. The cow finally realised its back was wet; it shook its horns vigorously. I came back to my work and completed what was left. I would be done after this. I moved on to the various writers who had patiently kept us company and began painting their words on the walls. I had accomplished a lot of this by the time light began to appear. People had come out onto the streets. I said we’d do more writing on the walls of the Sheba Sadan next Saturday. Our bodies were tired, even though we couldn’t feel the tiredness in the cold, but we did think that if we were deprived of hot tea any longer we would freeze. Near Hazra More a tea shop had resumed business, the gas had just been lit, and we harangued the shopkeeper, saying, Dada, make us some tea as soon as you can, or else you’ll have more work on your hands than you bargained for. We weren’t sure if he understood our meaning, but he quickly made us tea and handed it to us in glasses. I started warming my palms on the sides of the glasses, as though the tea were more crucial to returning life and warmth to us than as a beverage that had to be drunk. One glass of tea wasn’t enough; we ate some biscuits too and had several glasses more.

Upon returning home, there was only continuous sleep.

Sunday was our day off, so I would sleep late into the day.

That evening, a lot of people came over. But Sutanuka arrived first thing in the morning and said she’d gone at dawn and seen the exhibit. Her face was lit with a kind of approval that’s born of passion and wonder. And there was regret also, for not having been able to spend the whole night with us. I explained to her that we were attempting a project on a large scale and that she’d get many opportunities in the future. You have to stay with us, I said. She did, with great enthusiasm and a deep sense of duty.

*

Episode 4

Sir, choosing between beating up a thief or watching flowers being painted: it’s impossible to make such choices in a police station.

The Times of India, Delhi edition, front page, 10th January 1975

Sunil Ganguly on the chaloman shilpa andolan, 7th January 1975. The headline is ‘ khola haowae shilpa’ – ‘Art in the Open Air’.

There’s no end to my dreams. At the Indian Airlines office at Chittaranjan Avenue, I spoke to the Public Relations officer about wanting to paint on airplanes – I wanted to know how I should proceed. He wondered whether to laugh or cry, but I think he was persuaded to speak with me because he saw how young I was. He said that they hadn’t ever done or thought of anything like this before, that I should possibly write a letter which they would send to the head office, and then they’d get back to me about its decision. I realised he was being evasive, but told him I’d write a letter despite knowing it would achieve nothing: I told him it would work only if he communicated my thinking properly to the head office. I wrote to them as I’d promised to, and they replied with, expectedly, a No. This is was the liaison officer, an omnipresent being. Just within a few years, though, small planes in the US would begin to be painted on. The journal Span used to be delivered to my house regularly: it was in its pages that I discovered this.

So we failed to enter history. During the Indo-China war, thick walls had been erected in front of many offices in the city; those walls, and large sacks of sand, rose in front of every police station, too. One day, noting the wall around Bhowanipore Thana, I went in – there weren’t too many people inside. A policeman in white was beating a man mercilessly with a lathi and raining abuse on him. He wasn’t particularly moved upon noticing me, and kept at it while I watched him from a chair. I don’t know why, but several minutes later he came up to me and asked me what I wanted. By now, everything I’d prepared to say was jumbled in my head; I was struggling to find words. I want to draw some pictures on your outer wall, I said finally. It won’t cost you anything, I just need permission. He stared at me for a while, already exhausted from meting out punishment, undecided how to react. Eventually he said, Moshai, you expect me to watch you painting flowers while I’m beating up thieves? Such things aren’t possible in a police station. I said, Have you noticed the beautiful pictures painted on the cancer hospital right in front of you? Don’t you think they look nice? He said, That stuff doesn’t work in police stations, moshai. I said it’s precisely in stations that it’s necessary. It’ll put you in a good mood. This time he said agitatedly, Excellent, we won’t lock up criminals in police stations anymore, our days will be spent looking at pictures. I realised I shouldn’t waste any more time. While I’d been speaking to the officer, the half-dead offender on the floor had had time to recover a little. It would start again, and my departure pained him in particular.

At the Anandabazar office, Purnendu da would check up on our progress regularly, and, one day, he said, You people have done something historic! People will forget about political graffiti on walls now and will look, instead, upon pictures, poems, and stories. Our names began coming up in papers and journals. Around then, Sunil Ganguly wrote about us in Anandabazar Patrika, especially about my snake and lotus, saying it would be all over Calcutta one day. In the Delhi edition of Times of India, a report on the event appeared with a picture on the first page. The Bombay Times of India printed the story the next day.

The project swiftly started getting attention at a national level. There was pressure on us now to do more work. It was covered by Bangladesh’s popular journal Bichitra too. I went every day on the double-decker bus and wondered if the painting I’d done was fine. Yes, it still looked all right. A lot of people were standing and watching; other were looking on while passing by from buses and trams: this is exactly what I’d wanted. Discussion, criticism, dismissal, contempt, and praise were all being showered on it. Fellow artists were guarded in their comments. Some, whom I saw as my teachers, thought I’d sent art towards the gutter: should art go into the streets like this? Could art ever be placed beside garbage? It should be located in a pristine place. My manifesto had been quoted in some newspapers, and the debate was quite voluble. Partha was now a student of art at Rabindra Bharati, and every day he’d bring back a story. He said some teachers had named me, satirically, Dewal Paul (‘Wall’ Paul). I said, But that’s good: you shouldn’t worry. Do you think it’s possible to do this kind of work without facing opposition? Criticism is a sign of health – it means we’re on the right path. And people deemed to be irresponsible busybodies are always up for criticism. But I wasn’t concerned with coming in the way of anyone else’s plans. I was teaching myself to dream of the future. What I was trying to assert now would become reality in the years to come, a path that would open up further routes. There would be art on people’s bodies, on vehicles, on clothes; everywhere, on the streets, there would be art on the move, art without a sacred thread. Art would move with the people. Art would be Dynamic. Calcutta is a great canvas – this, though we hadn’t said it aloud, was our credo.

Every Saturday, we embarked on nocturnal adventures. We drew pictures on walls and painted poems, short stories, even essays. Upon seeing the poetry of Shakti and Purnendu da on walls, people approached us hoping their poetry would be painted in the same way too. Our team grew in number. Young men and women got involved; word came from outside Calcutta that people were trying to spread this idea in their own areas. At that point, there was no phone that would fit into the space of your palms, there was no easy way of disseminating information; yet we’d been successful in communicating with many. Sunil da said, If you want you can paint pictures on my car. At that point, Sunil da was editing Krittibas again and had repeatedly published on the Dynamic Art Movement in its issues. I wanted all of Calcutta to be an art gallery at that time, with paintings people could see from buses and trams.

[Author’s note: some of the sections above appeared first in journals and newspapers.]

*

Episode 5

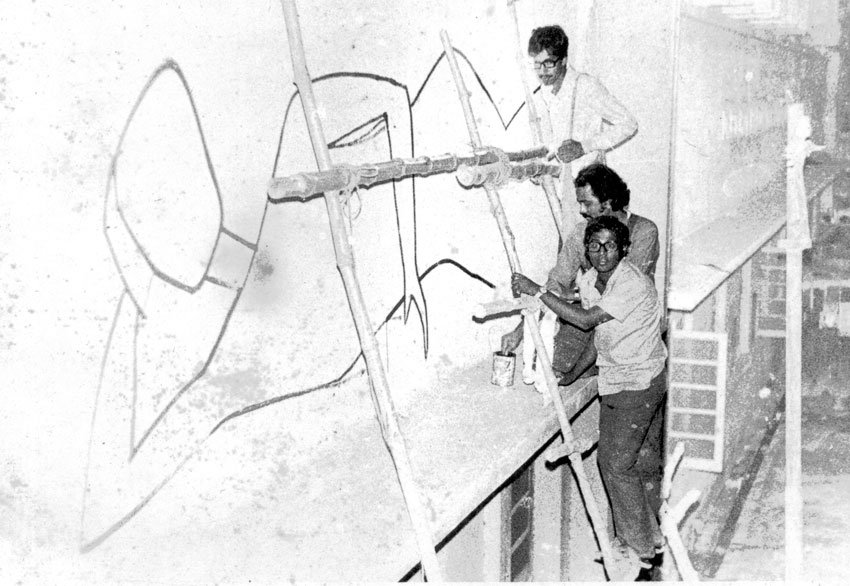

Painting at the National Medical College, Tapan Ghosh (in front) and Tapan Bhattacharya (behind Ashit Paul)

Meanwhile, a lot of people who wanted to join us had been contacting us through other people. We were working every Saturday night on multiple walls. One day, a young boy came to my office to talk to me. He said he was medical science at the National Medical College, that his name was Tapan Ghosh, and that he liked poetry, wrote regularly, and he’d come to me to make a request. The way in which we were presenting literature and art on the streets of Calcutta was, he said, in a word, spectacular. ‘I want to take you to our college with this art and writing: will you come?’ he asked. I felt enthused in turn by this young man; the very fact that one could have such a deep, almost radical, love for art while studying medical science was incredible to me. I told him that I’d go, but before that I’d have to check out the place: if it was to our liking we would need the permission of the authorities; besides, we would have to put a coat of paint on the walls, figure out a few things with regard to lights, with cordoning the place off and arranging for colours. Tapan said, We’ll do those things; just tell us when you’ll be able to do the work. I said, I’ll let you know in two days – meet me here then.

After consulting with everyone, we decided on a Saturday. Partha had already connected us with several students from Rabindra Bharati University. Tapashree, Samir, Atanu Basu, Neelima and his sister Shukla Sen were from there, and people were coming from several other places too. More Calcutta poets and writers were going to join us.

On arriving at Tapan’s hospital, we saw that all the arrangements had already been made by Calcutta’s doctors-to-be. We would have to work by climbing on to a platform that was about two storeys high, and we would have to keep our immediate surroundings in mind. There was very little space in the front; to work was to gamble a bit with our lives, but if anything happened, well, we were at a hospital! I was drawing such large figures on such a big wall, all of it through guesswork. That day, the medical students, men and women, created a festive atmosphere. They’d realised I was working on the hospital without a fee. This realisation fed into their excitement. Late into the night, there was an air of celebration. A pure joy lit up the faces of the young doctors-to-be. In this way they entered our dynamic art movement.

So Tapan Ghosh gradually became part of the inner circle of the dynamic art movement and took up duties on his own. Tapan was always there, supporting me, much like Partha had. Our old guard was unquestionably there too. The poet Samarendra Das’s family had close ties with the family of the poet Kavita Sinha, and Kavita di liked me as an artist. She was a producer at Akashvani – so I used to speak time and again on various subjects on the radio. In fact, Akashvani had brought out a spoken-word Puja Issue on the radio once, and I’d made a verbal announcement of its contents, in the way a magazine cover does. Kavita di decided she would run an hour-long segment on the Dynamic Art Movement. I spoke about the drunkard who, on that first night, had asked if colours would cure cancer. I pointed out that colours could possibly assuage cancer’s pain. If the pain that lies at the core of society – which people carry around inside them all the time – could be expressed through colour, it would find a bit of relief. Kavita di’s programme went so well she had to broadcast it again in a few days.

I was invited to the Calcutta Doordarshan studio to take part in a show; its centre was at Radha Studios at that time. Black and white TV had entered the households of many, if not all, people. There were local programmes in the evening, but, right after them, would begin the National Programme. That day I went to Radha Studios and found Pankaj Saha, Chaitali Dasgupta, and Pabitra Sarkar along with one of his students. She (the student) was to interview me, and Pabitra Sarkar was helping her prepare. Pankaj Saha and Chaitali were the producers of the event. It was a live one-hour programme. It was to be about my movement and my pictures. I didn’t have a TV in my home – so I wouldn’t have been able to see myself even if they’d shown a recording, but a girl in the neighbourhood who used to keep an eye on me daily watched it, and one day when I went out in the evening she called out to me from her verandah; when I went closer, she asked me to come to her house. I went and responded to a few things she was curious about. I realised then how powerful television was. None of my friends had watched it: none of them had TVs. And who stays at home after 6 PM?

*

Episode 6

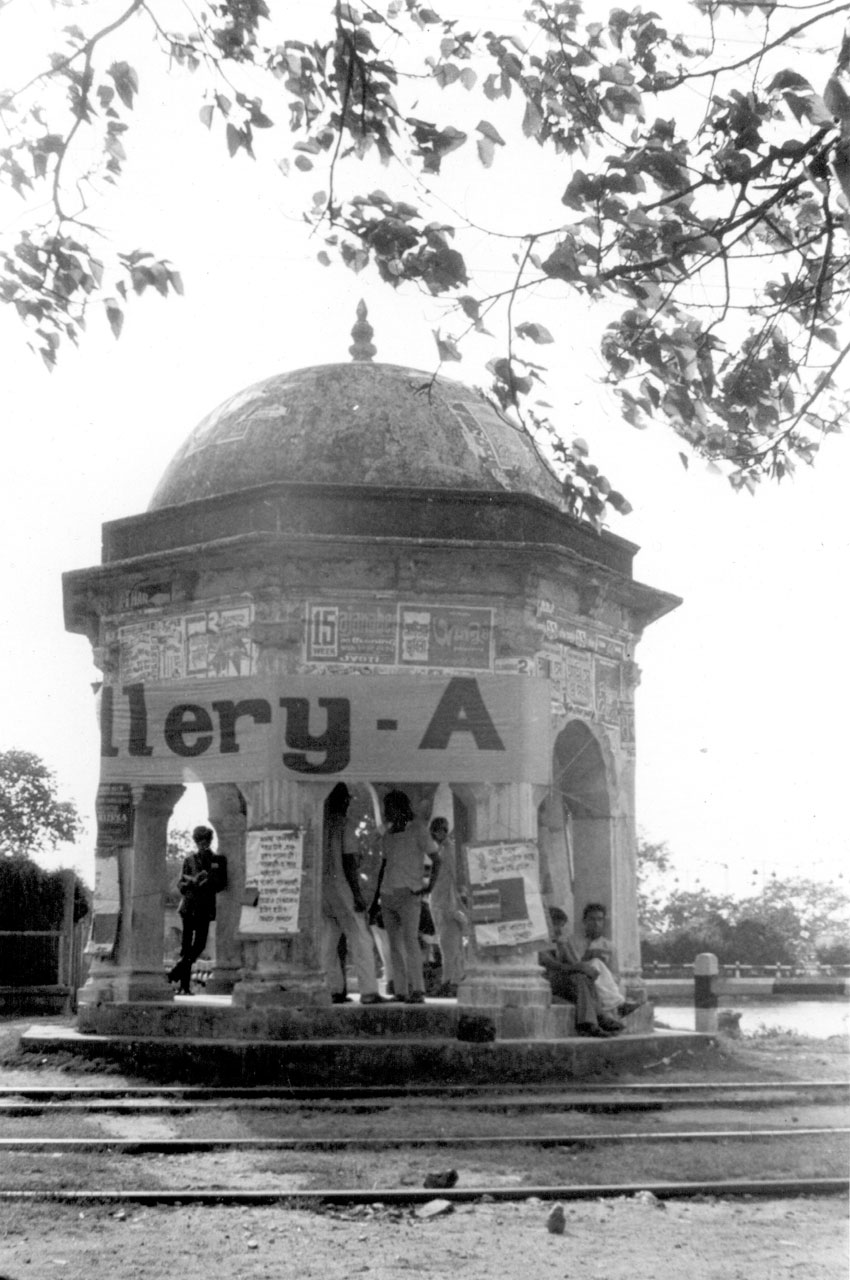

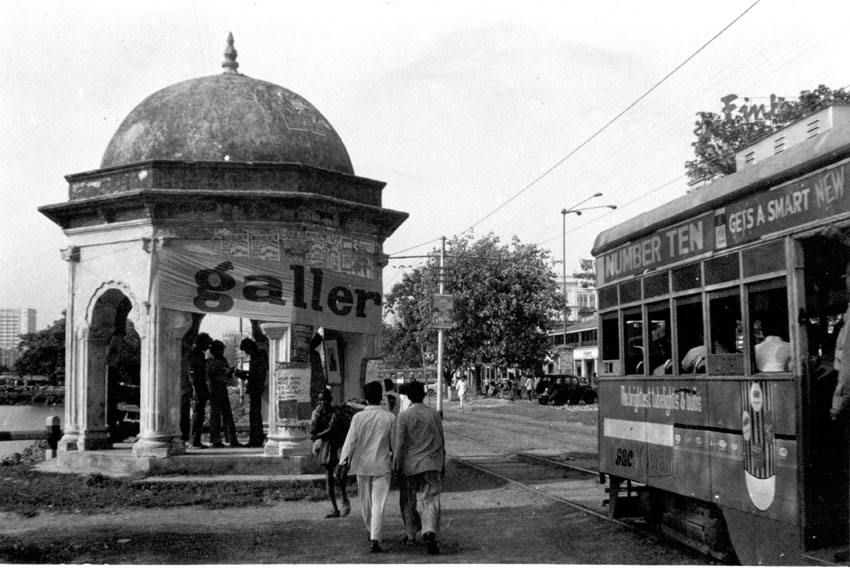

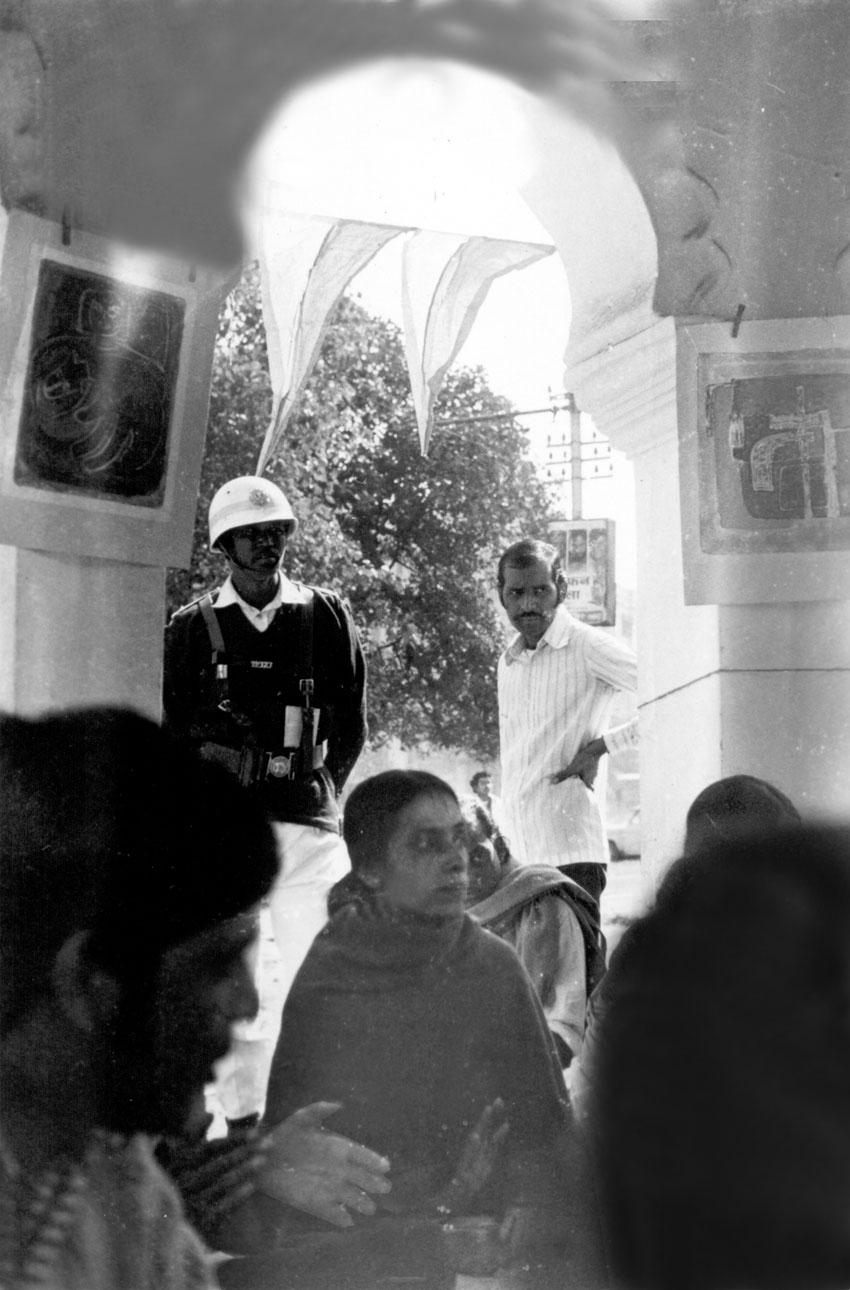

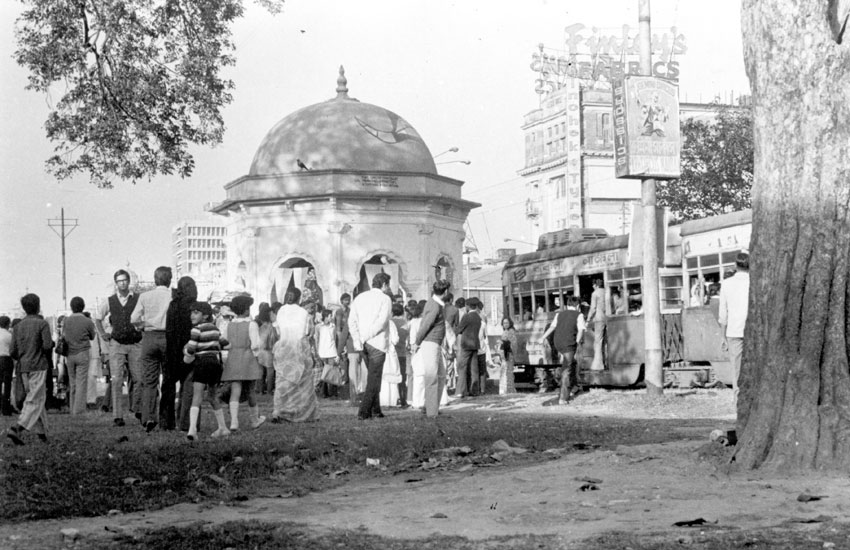

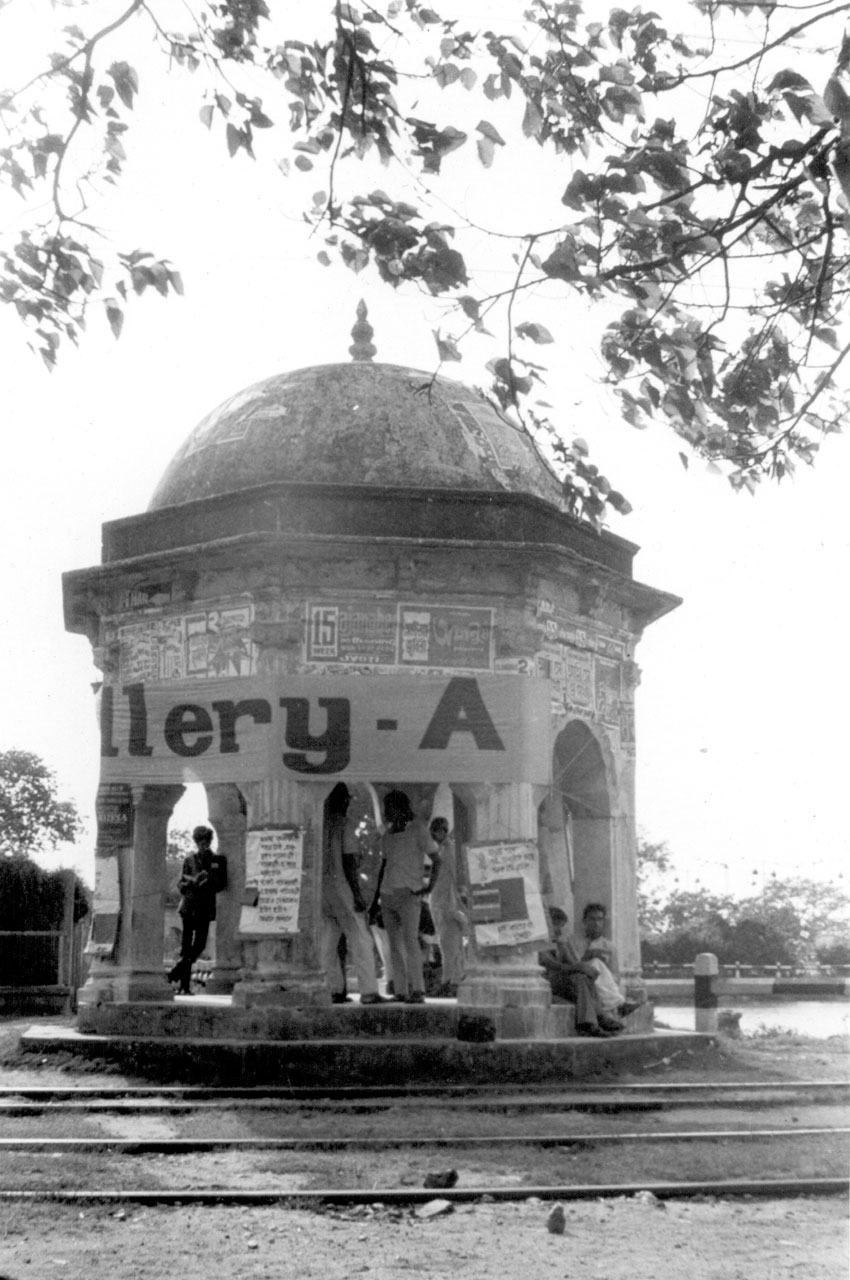

The new gallery, ‘Gallery A’, the domed building beside Chowringhee’s Manohar Das Tarag. All photos in this episode are from 1975.

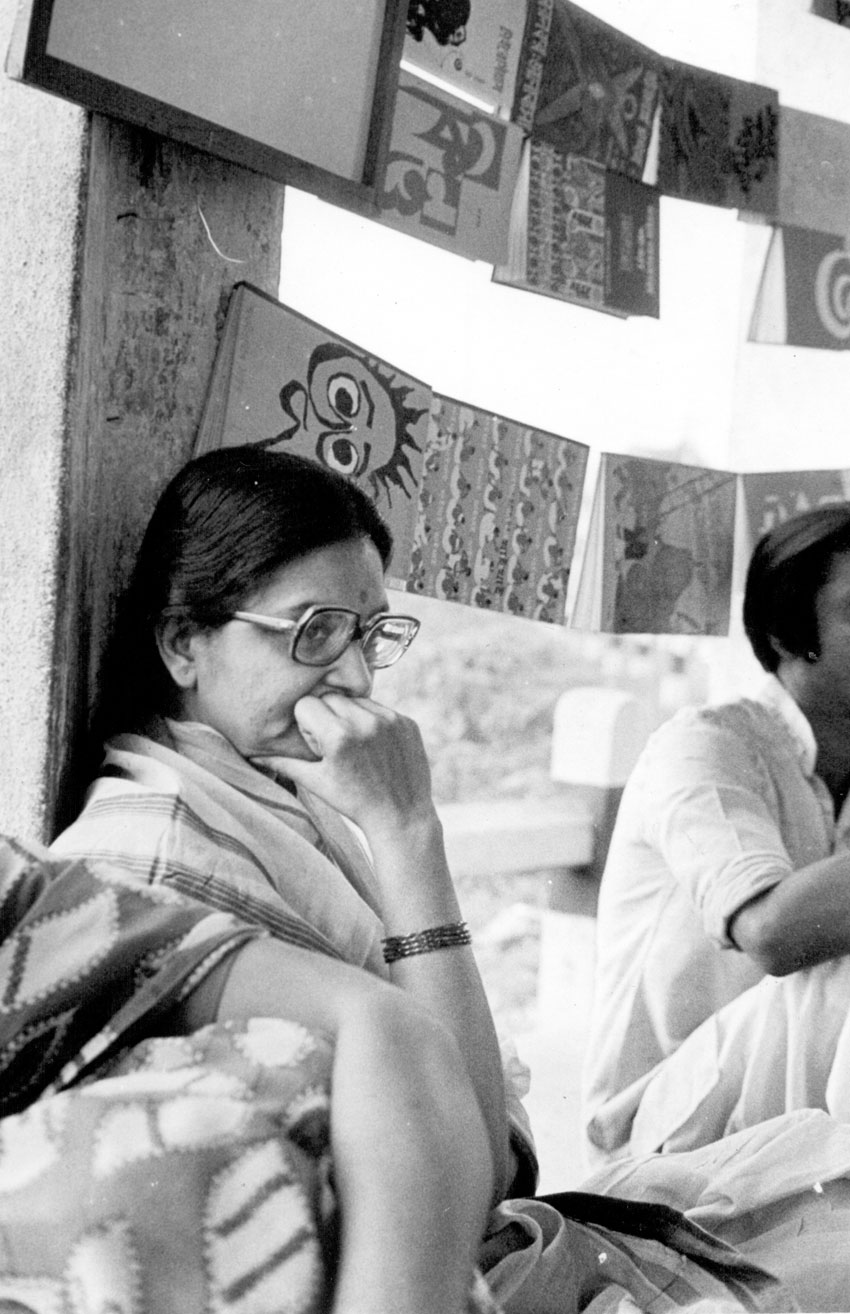

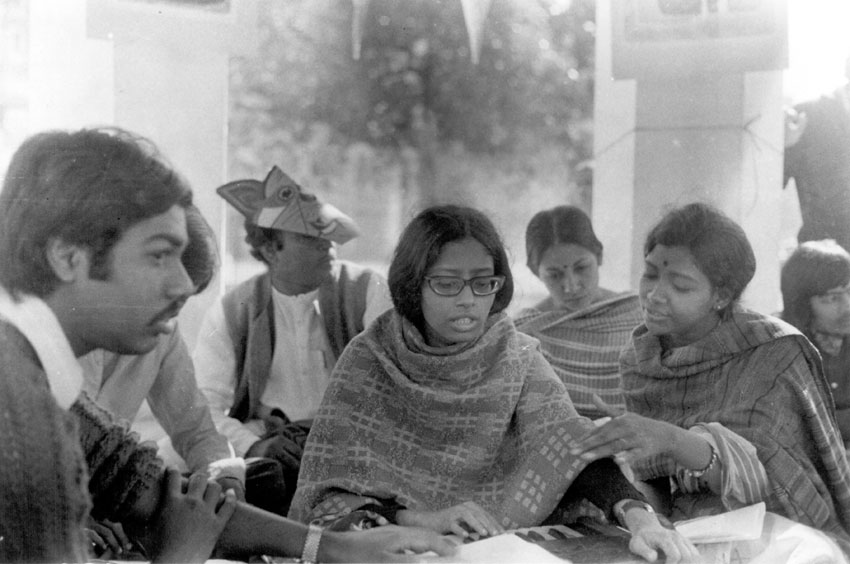

The young poet Sutanuka Bagchi sweeping the floor of the gallery.

The poet Kabita Sinha at the gallery, with little magazines and books meant to be read displayed in the background.

The gallery seen beside the tram line.

The gallery seen from a distance.

The poet Gautam Chaudhury.

Poster at the gallery. Its text says: ‘All of Calcutta is a great gallery. Gallery A is, in its midst, a pocket gallery. You’ll run into more galleries from time to time, here and there.’ The words on the left are chaloman Shilpa: ‘dynamic art’.

Tapan Ghosh, the young artist Moinak Shankar Ray, and others at a poetry reading at the gallery.

Shukla di prepares to display a poster.

I have to mention two things that happened in the midst of all this. The International Tri-Yearly Exhibition or the Triennale in Delhi used to be organised by the Lalit Kala Academy. The jury had come to Calcutta to look at paintings. I got news suddenly that a painting of mine had been selected; I’d have to send it to Delhi within a stipulated time.

I relaxed once I’d sent my picture, but now found I’d been invited to go there, all expenses paid. There I met a lot of people, like Vivan Sundaram, Geeta Kapur, the editor of the Lalit Kala magazine Jaya Appasamy, and various other artists. Word had it that Ramkinkar had made his sculpture Sujata with Jaya di in mind. Jaya di invited me to her house, and wanted to know in detail about our movement in Calcutta. I saw she was quite well-acquainted with it already. She told me the next edition of the Lalit Kala magazine would carry an interview with me about the movement and my paintings. Sandeep Sarkar had interviewed me.

I’d heard of the Madras Chola Mandalam movement: it was a colony for artists. Joseph James used to publish a journal from there, and I met him in Delhi on that visit. He said he’d like write about us in the next issue. I took heart from this pan-Indian enthusiasm for dynamic art.

The second incident happened after I returned to Calcutta and Lady summoned me to the academy; she said she wanted to do an exhibition of my works as soon as possible. I realised she’d assumed my movement stood against all gallery art. She’d concluded that I hadn’t been able to ignore the indignity meted out to Badal Sircar. I assured her that I wasn’t so much against galleries as I was for the doorways of galleries to be opened wider, turning them into a space to which everyone had unimpeded access. I did do an exhibition at her request. A card was printed, and invitations to the public were sent out by the painters Gopal Ghosh and Rathin Maitra, the joint heads of her organisation.

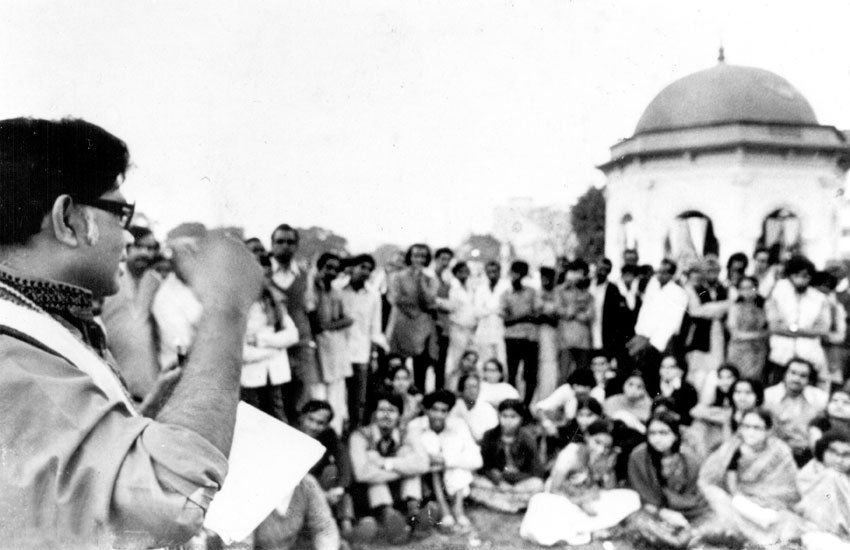

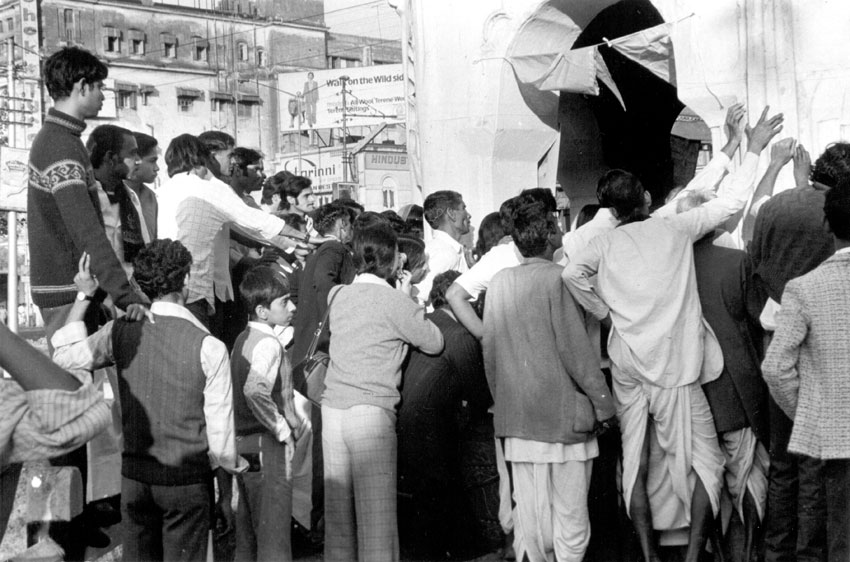

I have said before that the birthplace of many of my thoughts was the front seat of double decker buses. I was on the bus again, sitting right up front. I’d just seen Satyajit Ray’s Pratidwandi (The Adversary). Dhritiman Chaterji, the protagonist, had been hanging out, in the film, with hippies in one of the four domed structures beside Manohar Das Tarag [note: a ‘tank’ or waterbody off Chowringhee, with adjoining, domed mausoleum-like structures]. The hippies were probably high on marijuana. I’d see that dome every day from that bus; I used to see it earlier too, while going to college. Now I began to look at it differently. I shared my thoughts with the others. We’d give that domed structure a new purpose – as an open gallery. The plan was to transform it on Saturdays and Sundays. Pedestrians would walk by, looking on as they passed, or sit down to listen to poetry or music. This building was right beside the tramline, so we’d have to be careful. A warehouse for the new underground rail network was being created beside it. Its walls were covered in ivy. Everyone agreed immediately to the plan. Every bit of the domed building was covered with posters to do with various events in Calcutta. We’d start work soon. The YMCA hostel was opposite us. I went up on my own to talk to the guard there, and told him we’d like to keep some of our stuff with him: we’d decided to pay him monthly for this favour. He agreed as soon as he heard this. We thought we’d keep pictures, posters, banners, journals etc. over there. I wrote something that I then distributed to everyone in both English and Bengali versions, a leaflet that announced the open, free gallery.

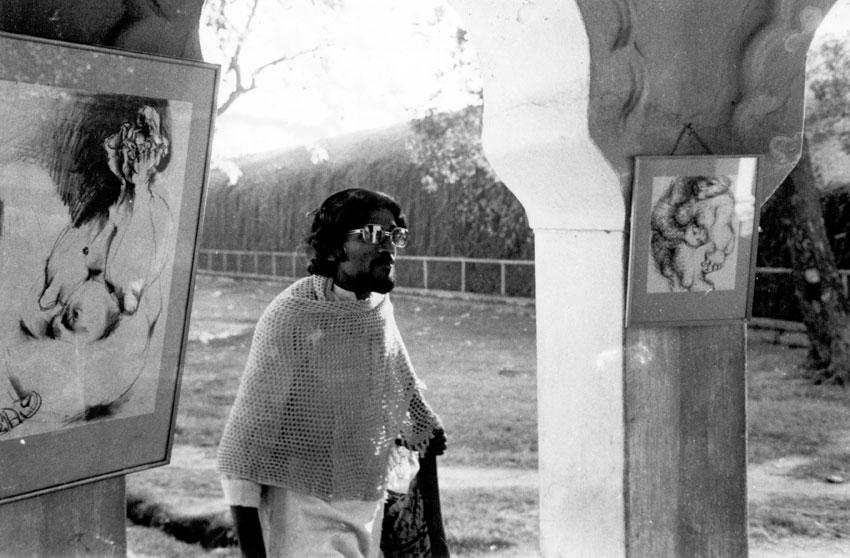

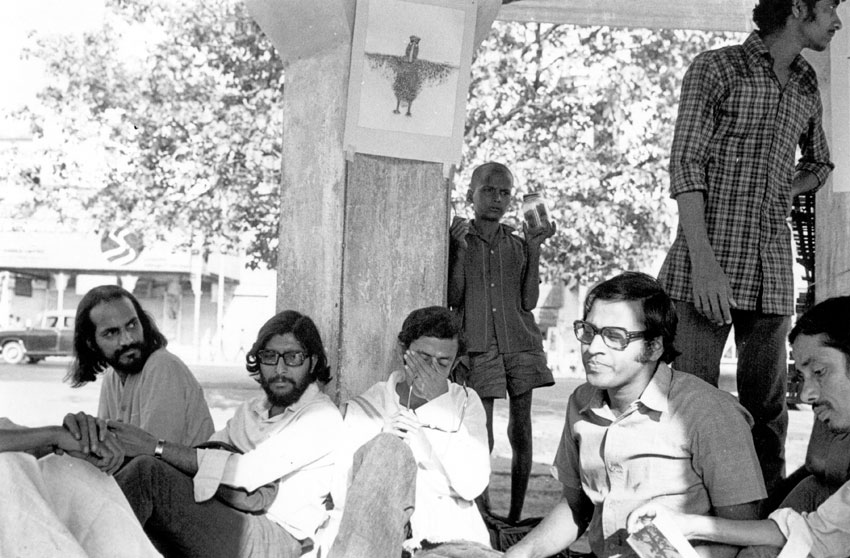

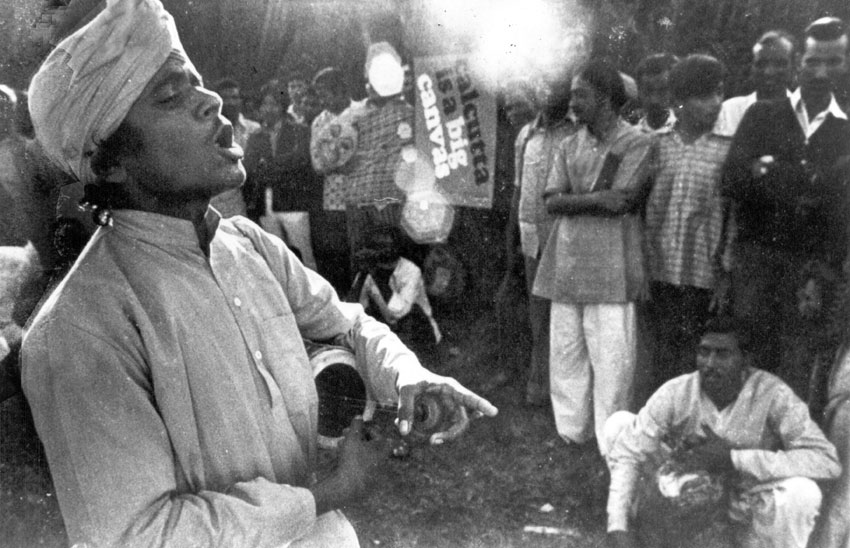

Around the middle of 1975, the event started with the exhibition of our friend Tapan Mitra’s paintings and with some poetry-readings. This was called Gallery A, with the hope that B, C, D would follow. We wrote upon a large banner and hung it up. Before we’d arrived here, this space was a den for addicts as well as a place in which vagabonds rested. Every day, the poets and artists themselves cleaned it up with brooms. Any painter whose work was being exhibited there would take on that responsibility. Gradually, people began coming in. One day, Ajit Pandey was brought in by someone; in those days, he was mesmerising audiences by singing about the Chasnala mining disaster. [Editor’s note: An explosion that was followed by flooding led to the death of 375 miners in Chasnala, now in the state of Jharkhand, on 27th December 1975.] His high-pitched voice drowned out the sound of the trams. This is how our gallery gradually came alive. Each day we’d raise money [payla] to get ourselves tea, and, if anything was left over from what we raised, we’d save it, with a record of expenses. When it grew dark, we would start packing up our things. Afterwards, some of us would go to Basushri Coffee House at Hazra More. The actor Anil Chatterjee would often be there, along with a lot of film club regulars. We kept a table reserved for ourselves. It was there, over coffee and pakoras, that our future endeavours would be discussed.

*

Episode 7

The gallery was adorned like a new bride.

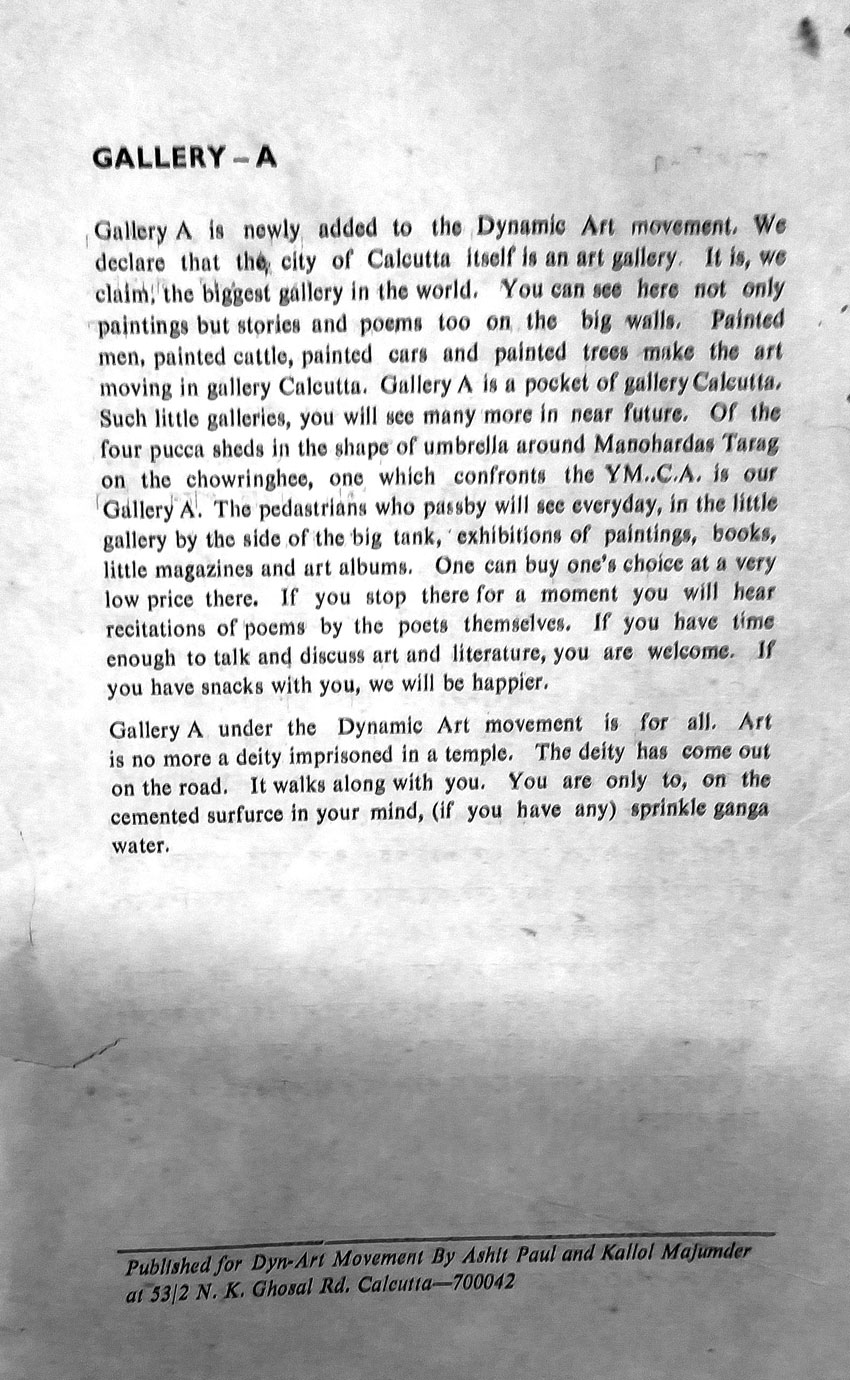

Pamphlet marking the start of the gallery: ‘Art is no more a deity imprisoned in a temple.’

The gallery takes on a new form, with the dome painted.

Sutanuka Bagchi singing. Swapan Shome (left) and Taposhree Sengupta (right) sing in chorus.

Traffic policeman sets work aside to be at the gallery, listening to songs and poems.

Every day, while travelling by bus, I saw that the dome had become discoloured, and realised we’d have to colour it again. A friend visited me at my house every Sunday, a friend who used to be by my side during bad times, a deeply cultured man, close to my heart, whose job was arranging contractual building work for the municipal corporation: Becharam Ghosh. One day I told him I had a request for his organisation, that they colour the dome once more so that I could paint on its roof again. He had a faint moustache under which was a faint smile. I don’t know who’ll actually do what, he said, but don’t worry, I’ll get it done, you’ll just need to credit our organisation by name on the site. There was a significant difference between his age and mine, and he loved to address me with the respectful ‘aapni’.

Becharam babu had to work hard to change the dome’s appearance. Cleaning it itself took a long time; then he had to apply a fresh coat of paint to it, so that it looked like a decked-up bride. Now we could paint on the top. There was a poetry reading that day at the gallery; Kamal Chakrabarty, who published a wonderful journal called Kaurabh, lived in Jamshedpur and had come to Calcutta specifically to be here. I was up on a raised platform painting pictures, and I could hear him singing folk songs. There was a throng of people down there – I was having to work very carefully, there was nothing to hold on to, and I’d be in deep trouble if I lost my balance even slightly. It took us until evening to finish the work. This was the Kamal who in the future would win the Bankim Prize and build Bhalo Pahar at Purulia.

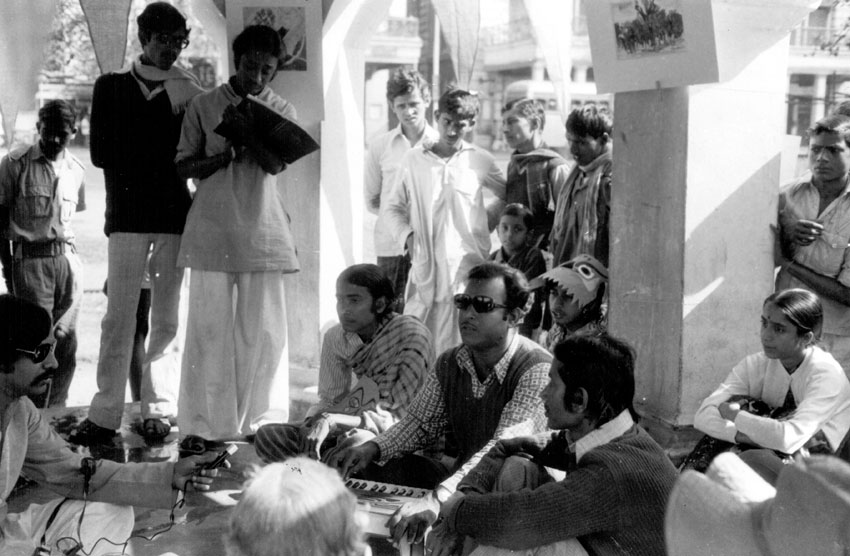

Every month, now, there was a new exhibition in our gallery; we were very lucky to be able to exhibit the pictures of Sunil Madhav Sen, Paritosh Sen, and Ramkinkar Baij. I’ll come back later to the way Ramkinkar’s work was brought here. Sunil Madhav Sen used to visit us in his ripe old age wearing a European-style hat on his head and with a silk scarf wrapped around his neck, driving up in a small Fiat car. To our gallery would come, often, Sunil Gangopadhyay; he’d read some of his poems and join us when we sang. Kavita Sinha came, read her poems, and asked other poets of her generation to come too. Rishin Mitra would, of his own accord, set poems by contemporary poets to new melodies and sing them with his harmonium. The convergence of poetry and music would change the atmosphere around the domed building in an instant, drawing a crowd from people passing nearby. Among us, Swapan Shome was a frequent performer; people would look forward to his songs. He used to sing lesser-known Tagore songs. Many young men from Tripura had joined the movement through their acquaintance with Partha; they all gave expression to their multifarious talents at our gallery. Partha used to sing very well – especially the songs of Sachin Deb Burman. For young poets to be able to read their poems here was a source of immense pride; back then they would literally break into fights at the Coffee House over who would get to read what. Samarendra Das used to keep in regular touch with them. One day a poet, on finding out he hadn’t been invited, threatened to blow up the gallery with a bomb. He came when everyone, one after the other, was reading out their poems, and stood on the pavement opposite the gallery: somebody whispered in my ear that he was there. I immediately went and brought him in and sat beside him. At the end, he read out his poetry too.

Shakti Chattopadhyay, Purnendu Pattrea, Utpal Basu, Bijaya Mukherjee, Sarat Mukhopadhyay, Pranab Mukhopadhyay – around four hundred and fifty poets and artists (in various media) came to the gallery at some point. Many of them are dead today; many made their name in their own fields. Joy Goswami, Mridul Dasgupta, Ranajit Das, Ekram Ali, Daud Haider, Sounak Lahiri and several others gathered there, including Hindi poets – we’d had no idea Calcutta had so many Hindi-language poets. Siddhesh Varma was responsible for bringing them together.

A lot of people wanted to know our whereabouts, but back then there was no way of communicating regularly; so we decided to publish a paper containing news and some information about our purpose. It was released bilingually every month. We named it Chaloman Shilpa Ka, Kha, Ga [Editor’s note: the last three words of the title are the first three consonants in the Bengali alphabet] in Bengali and Dyn Art A B C in English. We got our supply of paper from Pannalal Shil of Brabourne Road. I had taken paper from him before for an art magazine I’d produced; I think the paper used by most of Calcutta’s little magazines used to come from here. The owner of this business was Bholanath Shil, himself a writer of poetry who was very fond of me. He used to give us paper for every issue. This magazine was looked after mainly by Tapan Ghosh, Parthapratim Ganguly, Sutanuka Bagchi and a few others, and they themselves would figure out the arrangements for publication. Gradually, the magazine’s readership became substantial. A lot of people from outside Calcutta started to get interested. From time to time we got news that people were painting much like us in their own localities, and that writers were joining them, bringing literature to the project. They’d send us the news for us to bring out in our magazine. We didn’t do any of this through a committee. We thought of everyone as equal participants. People embraced their responsibilities as best as they could. Everything was decided through discussion. Our mode was the mode of thinking spontaneously.

*

Episode 8

Ramkinkar Baij at home in Santiniketan with members of the chaloman shilpa andolan.

Sunil Ganguly reading poetry at Manohar Das Tarag, 1976.

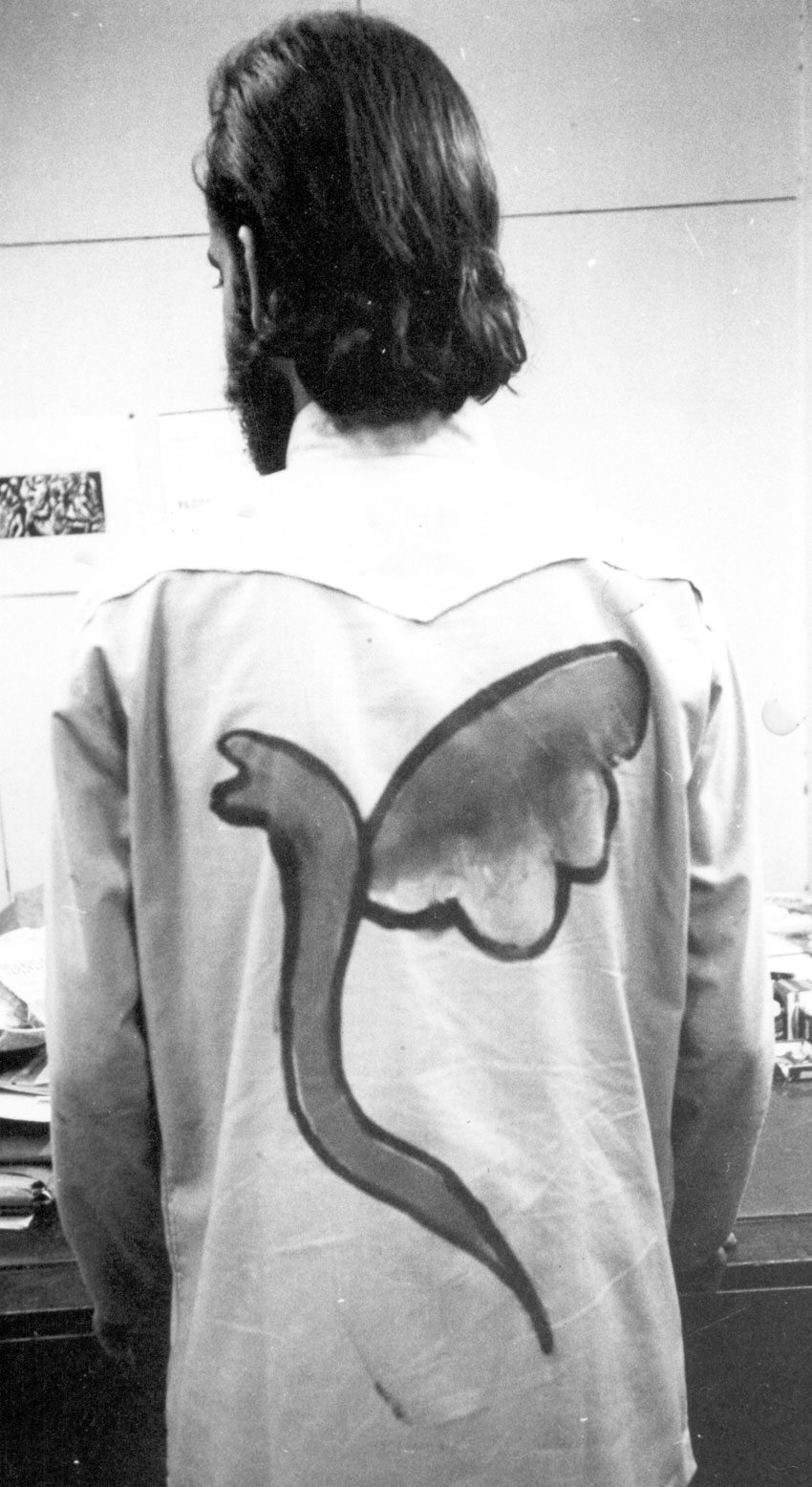

Ashit Paul painting the mountaineer Rama Dasgupta’s shirt, Manohar Das Tarag.

Ashit Paul painting the poet Gautam Chaudhury’s shirt outside Gallery A, 4th January 1976. All photos here are from 1976.

A dance performance at Gallery A.

A song by a Baul outside Gallery A.

‘Calcutta is a big canvas.’ Poster in background, Ashit Paul continues painting on Gautam Chaudhury’s shirt.

Rajeshwar Bhattacharya sings Tagore songs at Gallery A.

The musician Ananda Shankar (in glasses) and the dancer Tanusree Shankar, his wife, behind him.

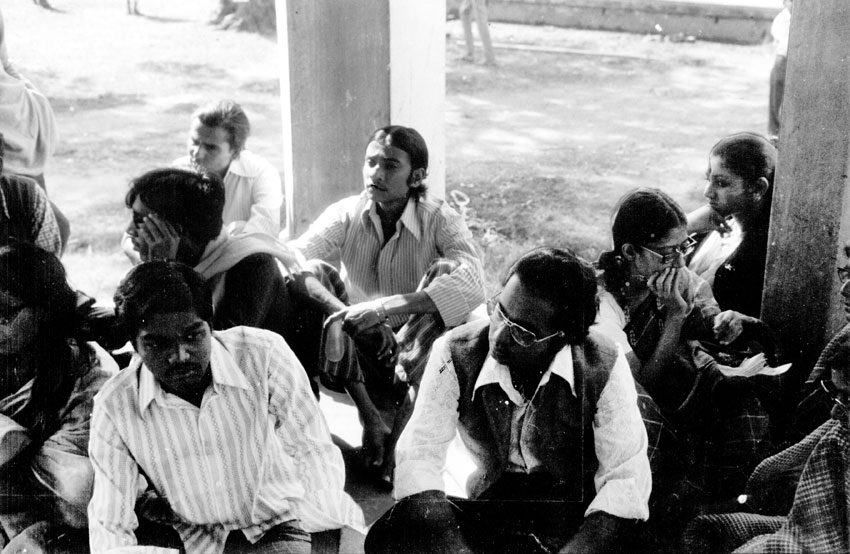

Visitors at the open air exhibition.

Gallery A beside the tram line.

Open air theatre outside Gallery A.

Audience looking on from outside Gallery A.

Ajit Pandey sings his own songs at Gallery A.

Santal dance outside Gallery A.

Samir Ghosh paints on the poet Shukla Chowdhury’s blouse.

Samir Ghosh paints on the shirt of the artist Parthapratim Ganguly.

A painting on the poet Jogabrata Chakrabarty’s shirt by Ashit Paul.

Before we knew it, we’d reached the end of the year. Our gallery had been running with regularity. There was an exhibition every month. At one point, we decided there should be an exhibition of Paritosh Sen’s work – he even agreed, but the pictures did not arrive. When I contacted him he said, How do I send them? A lot of people have told me not to share my paintings with your gallery. When I asked why, he said, Apparently tuberculosis patients sleep there all the time? I assured him that, even if they do spend time there, they aren’t there during the exhibitions – we regularly clean the place. Eventually, he gave us his paintings. We’d been moving through experiences of this sort. Every Saturday or Sunday, the gallery would be active; Partha, Samir Guha, Tapashree, Sutanuka, Samarendra, Sandeep Chatterjee, Kallol, Sambhu and a few others would take turns to open the gallery during the afternoon. Whether it was winter or summer, the gallery didn’t close; in fact, even during the rainy season, when Calcutta was flooded, the gallery opened on time. This is how we spent one whole year. Now we resolved to do a year-ending festival on 4th January. Everybody divided duties between themselves. Everyone was excited. Dipankar Saha has come to Calcutta from Agartala to study at Calcutta University: poetry was all he thought or cared about. He followed us us like a shadow. A lot of us went to Ramkinkar Baij’s earthen house at the Poush Mela and convinced him to let us start our year-end exhibition with his pictures. On returning to Calcutta, Dipankar was given the responsibility of taking a letter by hand to Ramkinkar and bringing back the paintings. I was a bit worried. In fact, I had good reason to be apprehensive. All his works were in Kala Bhavan’s control; Ramkinkar da wrote a letter for Dipankar to take to Dinkar Kaushik, who was then to give the paintings to Dipankar. But Kaushik was quite unhappy. These are people who paint on cow’s bodies, he said, Is it really possible to lend them the paintings? Dipankar went and reported this to Kinkar da. Kinkar da wrote once again saying, yes, he was more than happy for us to have the paintings. He asked Kaushik to comply.

Dipankar brought Kinkar da’s pictures and handed them to me. We were beside ourselves with joy. Purnendu da could hardly believe that Kinkar da had given us so many of his originals. He said he’d write about it in the Anandabazar Patrika column, Kolkatar Karcha.

4th January, 1976. The domed building and its surroundings were being decorated from the break of day, a colourful flag has been hoisted, and Kinkar da’s paintings had been hung up inside the structure. A lot of people’s paintings were hung up inside the godown of the Metro Rail, including Purnendu da’s. Bauls had arrived from Birbhum, and a Santal family from Santiniketan had come to dance for the event. A theatre group from Calcutta would perform a play on the field. Several events were lined up for the day. At one point I saw Ananda Shankar and his wife Tanusree Shankar sitting inside among the audience. Many among us wore painted masks, and were, therefore, not recognisable or identifiable. I and a few others were painting pictures on people’s clothes. Increasingly, it became difficult to manage the crowds; we had to very quickly organise means for the passage of trams, or there would be deep trouble.

In the meantime, Indira Gandhi had declared an Emergency across the country. In the crowd, I could discern white-uniform clad police officers. Sunil Ganguly had, in this time of distress, written a poem; he read it out for the first time in front of us: My heart is heavy; my heart is heavy. Many other poets had come: Kavita Sinha, Sarat Mukhopadhyay, Bijoya Mukherjee, Pranab Mukherjee, Ravishankar Bol, Mridul Dasgupta, Ekram Ali, Nasser Hossain, Ranajit Das, Parthapratim Kanjilal, Somnath Mukherjee, Sutapan Chattopadhyay (he was a short story writer, and had an intimate relationship with the gallery), Samar Mukherjee, Debashish Banerjee, Debashish Das, Joy Goswami and others. That day, Swapan Shome (who had been singing from the start of the gallery), Hrishin Mitra, Ajit Pandey, Rajeshwar Bhattacharya and many other singers were present, and an extraordinary dance took place inside. This bit of the Maidan was, that day, like a spring festival in the winter. Evening had come, but the poetry and music continued by candlelight; Sunil da was singing ‘Jaya taba ananda’ [‘Joy, you reign supreme] …and everyone sang with him.

It ended this way, with everyone singing together. It’s as though no one wanted to leave anymore, though many had been there since the morning; yet no one had succumbed to tiredness. That day, too, we raised donations and got ourselves tea, and Sunil da joined us.

*

Episode 9

The Emergency was declared across the nation.

And Agartala was revolting now, using our out-of-the-box thinking.

Freedom of Art: the movement’s thoughts collected in one place

The mouthpiece of Dynamic Art: Dynamic Art Ka, Kha, Ga

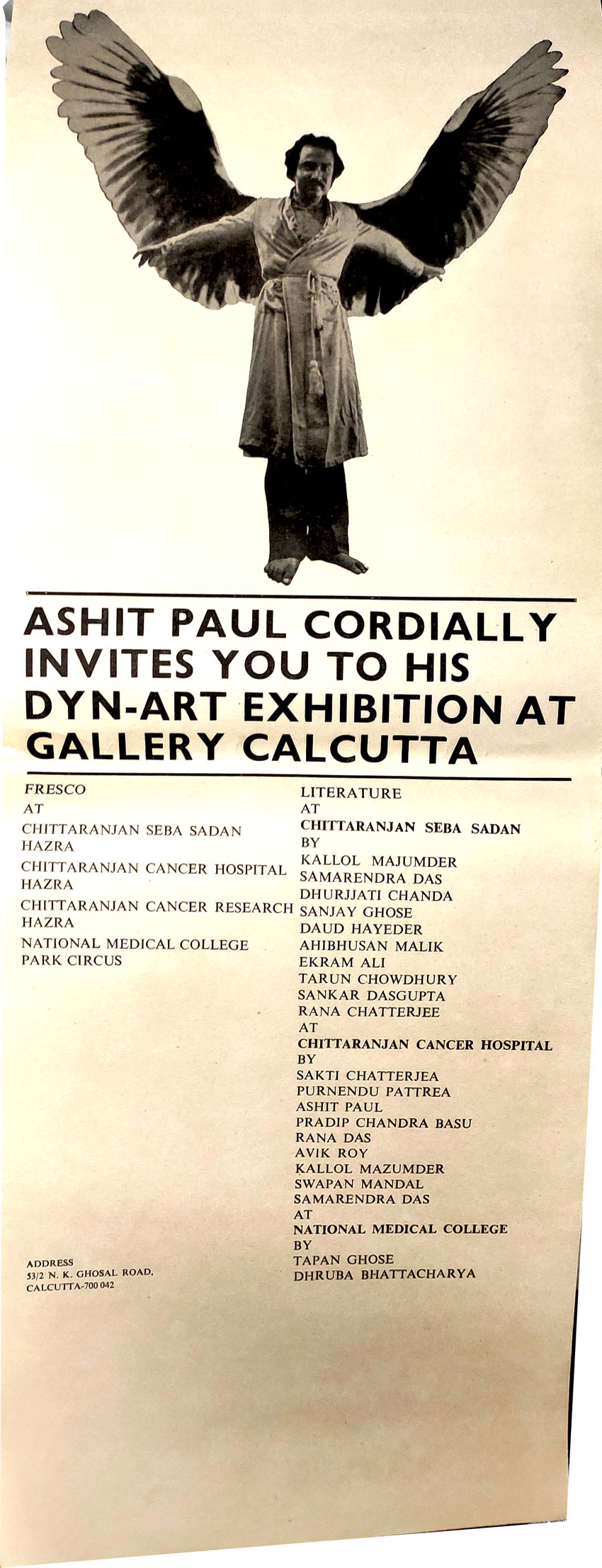

‘We made a list of the places at which our work had taken place, and of the people who had worked there, and created an invitation card. This invitation was a bit of a departure, in that it had a picture of me as a winged human in flight.’

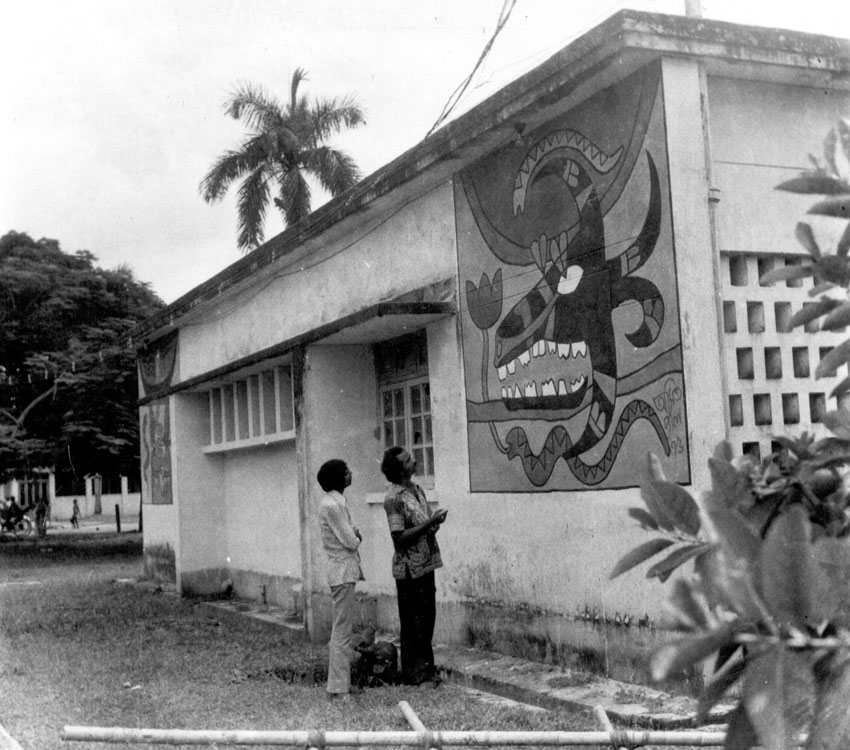

Paintings done on the walls of Agartala’s Sadar Hospital.

Paintings done on the walls of Agartala’s Sadar Hospital.

Paintings done on the walls of Agartala’s Sadar Hospital.

Paintings done on the walls of Agartala’s Sadar Hospital.

We were confronted now with a huge complication: of having to tread carefully because of the Emergency. A lot of journalists were lying low. There were many things that could no longer be written; opinions were becoming hard to express openly. Yet there were a lot of people who wanted to raise their voices. The life of our magazine and gallery continued uninterrupted, and the number of visitors from faraway places was growing.

While all these changes were taking place during the Emergency, Barun Sengupta and Gour Kishore Ghosh of Anandabazar Patrika were being arrested by the police under West Bengal’s Chief Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray. In protest, Anandabazar had published a white space as an editorial. I used to see the overcautiousness in newsrooms, every article of news first having to get the stamp of approval from the censors: only then would it appear in print. Even though Jyotirmoy Datta didn’t work for Anandabazar, he used to come barefoot to its office frequently. He used to write editorials for the Hindustan Standard, and his magazine, Kolkata, had also become full of revolutionary writings. One day he came and asked me if I would make some posters for him. He said they would go and paste them on the statue of Gandhi after midnight. No one would get to know my name, he assured me. I didn’t hesitate to make the posters.

MF Husain was doing an exhibition at the Academy for his Bharat Mata series of paintings. I went there and saw that he’d equated Bharat Mata [‘Mother India’] with Indira Gandhi on some very large canvases. I felt quite depressed. What had happened to Husain? I wondered. Why was an artist of his stature pandering to the government? I’d written an editorial in my magazine, Artist, where I’d been as critical as possible about the Emergency. That piece of writing had been necessary to keep my mind as calm as it was possible for it to be. I made no attempt to find out if it had caught Husain’s attention. Readers had sent me their responses from faraway places.

In the meantime, I thought about presenting Calcutta in a slightly different way – to do with the way our work in many places had been impelled by the idea that Calcutta itself was a gallery. So we made a list of the places at which our work had taken place, and of the people who had worked there, and created an invitation card. This invitation was a bit of a departure, in that it had a picture of me as a winged human in flight. To be honest, no one will think of taking a second look at something that isn’t slightly outrageous. This has become normal behaviour in people.

Partha and Dipankar decided they would take me to Agartala – a lot of people wanted the idea of dynamic art to spread in the state of Tripura. After much thought, it was decided there would be an exhibition of my work as well, and the walls would be painted. People were looking forward to seeing what we’d do. We had gone back to Agartala after nearly five years. Human warmth is the lifeblood of this small town. People treat guests as their own very easily in Tripura.

I got on the plane with my pictures. Partha and the others had already reached Tripura. When I got there, I saw many people had, by then, arrived at Partha’s house. Partha’s brother Manas Ganguly and his wife were both theatre people, and their group Rupam Goshti was a theatre group of the first rank in Agartala. They had been very cordial with me – I’ll never forget that. Arrangements for my stay had been made at their place. We talked and made plans late into the night. Nilip Poddar, Ratul Deb Barman, and Dipankar Saha were there along with many others. In the morning, we were to inspect the wall of Sadar Hospital. Bhaskar Bipul Saha was employed in a significant position in the Tripura Museum; he had graduated from Santiniketan. They’d all reserved this particular wall for me as the site of my exhibition. I noticed how many changes had taken place since I’d been to Agartala five years ago.

We’d wanted a forum for discussion at the exhibition, and arrangements were made for this. We’d decided that I would draw on two of the walls of the Sadar Hospital, and Partha, Nileep Poddar and their friends organised the lights and everything else we needed. Nileep had recently come to people’s attention because he was publishing a journal called Pounomi, both in Tripura and in Calcutta. At night, when everyone was asleep, I was painting pictures in bright lights from the top of a dais. We stayed up two nights in a row to finish the work. They were delighted with the result. This was the beginning of the Dynamic Art Movement in Agartala. Local journals began to write about it. Kartik Lahiri, a highly regarded writer, and other artists and writers had been among the participants in a discussion on the unfettering of art at the start of the exhibition. I had asked for our discussion to take place in candlelight – that way, we’d become semi-visible and who we were would become less significant. The debate heated up that evening in partial darkness! Never in Agartala had such weird ideas been introduced; as a result, there was contestation at every step, and, as in Calcutta, argumentation remained my constant companion. I tried to effect a 180-degree turn in the way they looked at art. Actually, there’s a fault in the way we think about art. We prefer to move within boundaries set by the herd. Textbook learning circumscribes our thought. In Agartala, the wave of the dynamic touched many young minds. This would inform the future of art in Agartala.

Our Dynamic Art Movement and gallery ran till 1977. We’d have a wonderful festive programme in January every year,. Artists and writers came to Calcutta all year round and read poems and sang songs, and people from different walks of life comprised our audience. We brought out a special issue on behalf of the Dynamic Art Movement in which we published interviews with people from the world of culture. We consider this a historical document. We called the collection, in English, Freedom of Art. Why should we not paint on the corporation’s big iron-wheeled car that was meant for garbage disposal? People who were obsessive about cleanliness and hygiene had a problem with paintings being located in such spaces. I wanted to break with this. Everyone across the world has, by now, seen the effects such a change can bring.

*

Episode 10

Then came a terrifying time

Our pictures began to be erased from walls – the reason cited was the Emergency

Our gallery was going to be destroyed because of the Metro

Letters of protest and reports about the planned demolition of the domed building, ‘Gallery A’, in the Anandabazar Patrika and Jugantar, 1977

Letters to the Editor, Hindustan Standard, Hindi-language newspaper Sanman, and Amrita Bazar Patrika, 1977.

Letters and reports, Basumati, Amrita Bazar Patrika, and Anandabazar Patrika 1977.

One day we heard some awful news. The police had begun erasing our work from walls. Exactly what I had feared had transpired. They had wiped away all our art and writing. We were angry, and in pain, but kept the pain and anger to ourselves. How was this possible? we wondered. We hadn’t put up any political writings or paintings; why had our art been targeted? We sent a letter of protest to the Commissioner of Police. Others wrote to Lalbazar [police headquarters in Calcutta] in protest. A few days later the Commissioner replied, expressing regret. He said all of this had been done unintentionally, and heaped the entire blame on to the lower rung of policemen.

We were heartbroken. We were trying to keep it together when a journalist friend of ours came and gave us more bad news. He had heard from Writers Building [the state government headquarters] that the domed structure was to be demolished because of the ongoing Metro Rail works. I was startled. Jatin Chakroborty was the Public Works minister at that point; the journalist had registered a protest with Jatin babu on our behalf. He told us we mustn’t give in to this development; that he would get a letter of protest delivered if we wrote one. And that we should prepare to protest together.

I knew the ministry would have been informed by Metro Rail about how they intended to proceed, and told that this work was in the state’s interest.

I spoke to Sunil da about my depression – he listened to me and said he would have done something if it would have helped. We should all sign a letter; the ministry wouldn’t waver unless it was faced with public consensus. That letter appeared in all journals, and it was signed by artists, poets, and writers. Those who stood beside us included Sunil Ganguly, Shakti Chattopadhyaya, Purnendu Pattrea, Shirshendu Mukherjee, Dibyendu Palit, Shyamal Ganguly, Nabanita Deb Sen, Krishna Dhar, Nikhil Sarkar, Amitava Chaudhuri, Prafulla Roy, Gouranga Bhowmick, Shudhhasheel Basu, Ahibhushan Mallick, Rajeshwar Bhattacharya, Subrato Sengupta, Pabitra Mukhopadhyay, Shekhar Basu and many others.

The Public Works Minister – Jatin Chakraborty – informed us through that journalist that he’d like to meet us. We said, That’s fine, give us a time and date and we could meet in front of that very domed structure. He arrived there one evening and told us in that hoarse voice of his that, while it was true the domed building would be demolished, it would be reconstructed exactly on the lines of the original the moment the Metro Rail’s work was finished. I grant you’ve grown sentimentally attached to that building, he said, So, for as long as work on the underground railway lines continues, the Public Works department will create a new gallery at Curzon Park for you. He said he’d ask the Chief Engineer to proceed in consultation with us. We listened carefully. We didn’t offer an opinion, and said we’d let him know what we’d decided after discussing his proposal amongst ourselves. We gave it serious thought. Many felt that it would be best to agree, given the Minister had promised he would rebuild the domed structure. We would work at the gallery at Curzon Park till it was returned to us.

We sent word through the journalist. On seeing that I was depressed Sunil da told me one day that I had achieved a great deal of what I had attempted to: many movements over the world have had, likewise, a brief duration; they’ve played their part in history; let this one’s memory stay with the people – prolonging the movement will blunt its edge. There was a point to Sunil da’s argument. I thought a lot about it – if people had indeed been touched by the ripple we’d created over these past three years, then change would come.

I spoke to the Chief Engineer at the Writers Building more than once, and he showed us the drawing of a huge plan. I brought the plan back home with me.

I thought to myself, to take anything from the government we’d need legal approval, which we didn’t have, and didn’t wish to have. We didn’t want to get enmeshed in this kind of complexity. All this time we had worked without a committee. We were conscious of the fact that we were involved as equals, which is why the thought of committees had never entered our heads. And to now move in this direction would be to get entangled in tussles of self-interest. Tussles to do with reputations, tussles to do with ability. Keeping Sunil da’s advice in mind, I began to wind up. I didn’t go back to Writers Building, and the plan stayed with me.

*

Episode 11

The feeling for revolution had become deep-seated in people

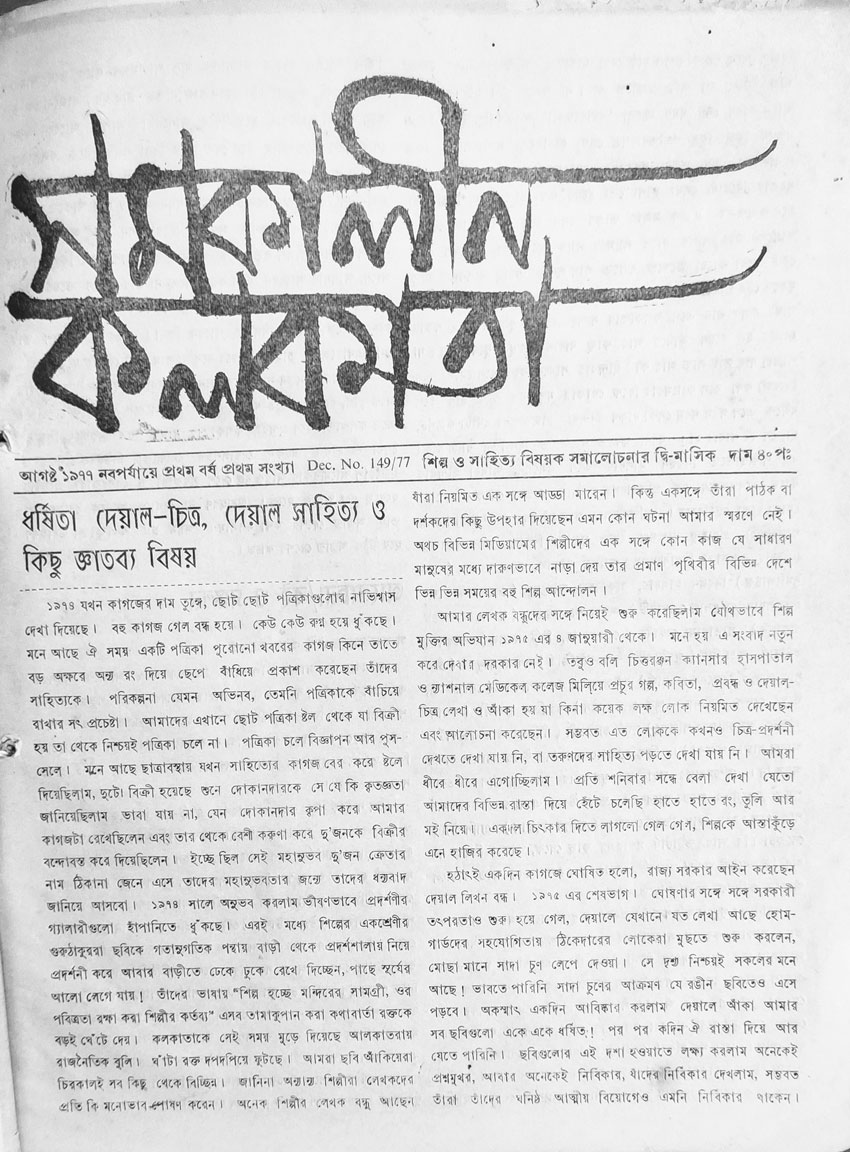

The first page of Samakalin Kolkata (Contemporary Calcutta)

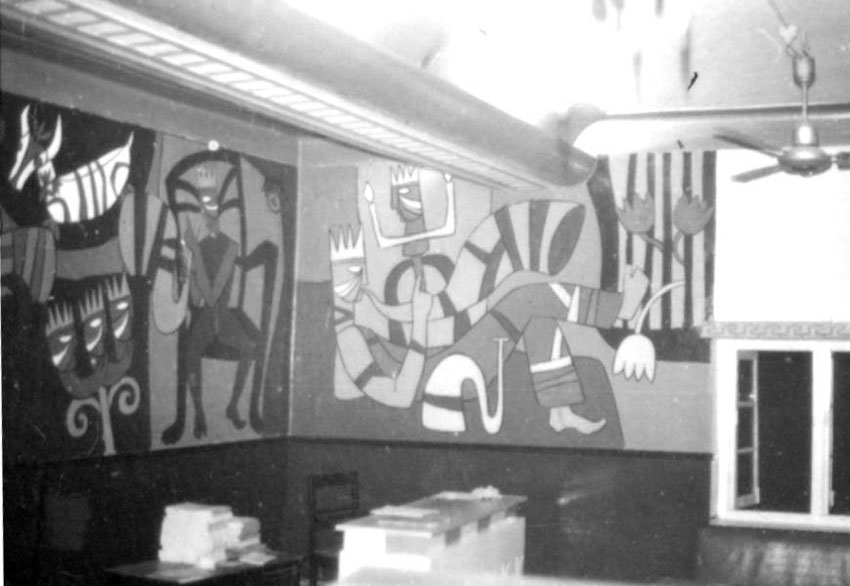

‘Musician’: the painting by Ashit Paul inside Basusree Coffee House.

‘Musician’: the painting by Ashit Paul inside Basusree Coffee House.

‘Musician’: the painting by Ashit Paul inside Basusree Coffee House.

We’d gather regularly at the Basusree Coffee House. We’d have something to eat too. Everybody was depressed. I could tell that Dipankar Saha, an introverted poet, had some other kind of tumult going on inside him. Partha, Tapashree, Tapan, Kallol, Samarendra – everyone was down-hearted. Partha and Tapashree would, of course, come to my house every Sunday to get my views on how their own art was progressing. Every now and then, Dipankar, instead of going back home, would come to my place after eating out at night; I’d work late into the night, and he’d stay up to write. Dipankar said a lot of people were curious about what our plans were, and suggested we bring out a publication keeping them in mind. I said, I don’t want to say anything about dynamic art in a publication anymore; that might have made more sense if we’d been active. Then I said he could publish a journal if he wanted to, but that it would have to a venue for critique, for expressing thoughts from our perspective. It would be about art and culture in Calcutta, but would carry no poetry or stories. It would look very plain. Is that okay with you? I asked. Without being in the last taken aback, Dipankar said it would be wonderful to have such a journal, particularly because no one is publishing this sort of thing. I said, Then it’s fine, we can think more about this, and you can be the editor. You can do it, right? I asked him. He knew I was saying this because I wanted him to step out of the shadows.

After having been active without interruption for almost three years, the Dynamic Art Movement ended. But it continued to resonate in people’s lives. The ‘dynamic’ warriors would reassemble after twenty five years.

Chiku Madan, the proprietor of Basusree Coffee House, was sitting at the counter one night; he’d arrive there now and again towards the evening. He’d got to know us quite well. One day he told me, ‘I have something to say’, and I thought he’d tell me we occupy the place for too long (just as Anil Chatterjee and his friends sat and talked for long spells). I asked him what was on his mind, and he told me in his broken Bengali to do a painting on the wall of his café – he would provide colours and brushes. I realized he was trying to make commercial use of my paintings without paying me anything. Then I thought – but this hadn’t occurred to him before; it was after our movement that it had dawned on him that even the Coffee House could be embellished! I said a picture of this size would require a long time, and it would be hard to paint at the coffee house during working hours; maybe we could do a bit after business had ended. We gave him our word; we’d have to be there frequently now to keep him happy.

We’d keep our adda going on for a bit longer than usual and then start work. It took us quite a few days to finish it. Every night I continued working while tables and chairs were being cleaned.

I was doing some work on musicians at that point, and the painting at Basusree Coffee House – of trumpeters – became part of that series. It was a big work. I was helped throughout by Partha and Samir Gupta. Chiku Madan was quick in his appreciation; he expressed his gratitude through a letter and informed me that my family and I could drink coffee free of cost here forever. I didn’t take advantage of the offer, though.

Even though our movement has ended, the ideas we planted have continued to bear fruit. A new idea of Bengali culture came into existence – as recorded by our periodical Samakalin Kolkata (Contemporary Calcutta)– and our movement’s role continues to be acknowledged by writers and artists. The movement gradually spread through the country and beyond it. We had started it, and those who believe our kind of thinking necessary for art and the world will perhaps achieve something even bigger. We never thought we were doing something huge, but at least we’d been able to move a rock a tiny bit forward.

*

Episode 12

Our movement ended, having reverberated in the international scene.

Painting buses in the Rabindra Sadan area led by Shanu Lahiri.

In 2001, with Shanu Lahiri in front of a painted bus.

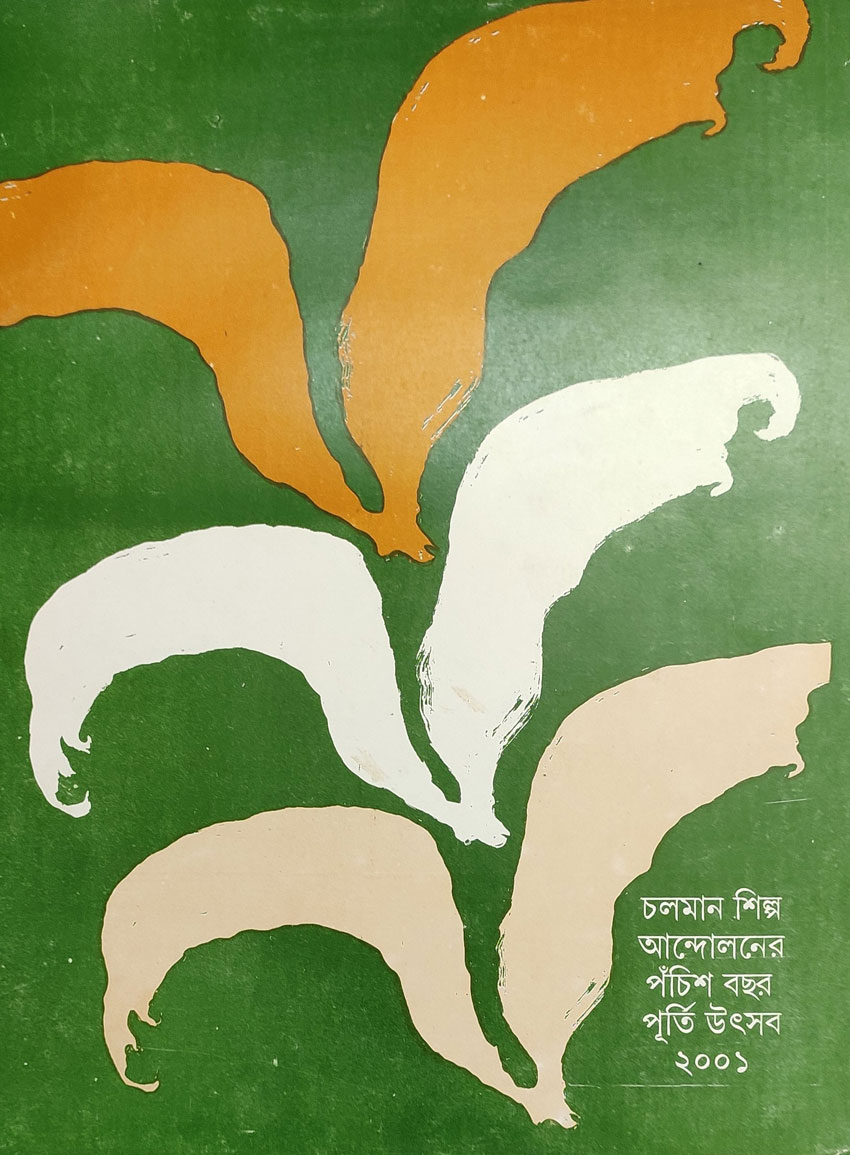

A commemorative volume on the occasion of the 25th anniversary.

25th celebration of Chaloman Shilpa 2001Teracota memento by Ramkumar Manna.

What I have written so far about the Dynamic Art Movement is meant to draw it to the attention of today’s artists: it wasn’t my intention to write a history. The history would be much more dense: there are many events and several people I haven’t mentioned, which doesn’t mean that the contribution of those I haven’t mentioned was less than others’; I have mainly cited names which were organically tied to the events I’ve described. There are others who have been leading their lives since then, doing various kinds of work: I want to write about them in the future. This movement took place over the space of three years. Many have attempted, later, to extend the legacy of this movement. My job had only been to unlock a door. We did the work; history will decide if it wants to recall or discard us. But I haven’t taken on the job of writing history. Anyone who thinks it’s necessary to write about this movement should, of course. At that moment, we’d mostly thought about keeping on working; most of us were less than thirty years old, I was twenty five, and there was probably a feeling for the bohemian life among many of us at that point. But we were in it together, holding hands in solidarity. There was none of the conflict caused by self-interest.

Even after the movement ended, a few people, including myself, resolved to continue exploring the domain of Public Art, and finished quite a few works done along those lines. Their preservation was compromised by the negligence of government officials. In fact, I’d even pleaded with the government to give me some hoarding-space for the juxtaposition of paintings and literary fragments. I’d shown them my plans for this project, and the government had retreated after having seemed enthusiastic at first, for reasons unknown to me. A lot of ideas were nipped in the bud in this way. This was during the rule of the Left Front government.

Some people asked us to write about the 25th anniversary. I’d responded with humility that I wanted to write about the movement, not about the festivities. The difference between the main movement and the 25th anniversary celebrations is significant.

A festival was held in 2001 to mark the anniversary – the result, mainly, of the poet Nasser Hussain’s enthusiasm. Many poets and artists came, as did those who were still alive among the movement’s participants. The festival took place around the Rabindra Sadan as well as other places. Led by Shanu Lahiri, a lot of artists painted upon the exteriors of government buses. Many artists and performers joined us: Usha Ganguly, Rudraprasad Sengupta, Swatilekha Sengupta, Prabir Guha, Srikanta Acharya, Amar Pal, Pratul Mukhopadhyay, Badhan Das, Hiron Mitra, Jogen Chowdhury, Dhiraj Choudhary, Atin Basak, Tarun De, Anita Roy Chowdhury, Sahaj Ma – so many names and enthusiasts as well as the money we raised came together to make this festival possible.

The reason we’d decided at one point not to form a committee or accept offers from the government, the reason we chose not to be tied down by institutional demands, was because we feared self-interest would begin to dominate, we’d stop recognising ourselves, and the arrogance of reputation would raise its ugly head. In 2001, we found a few self-interested people among us, whose individual causes were the opposite of ours – which is why we had to bring things to a close without thinking too far into the future. The spontaneity of the original movement wouldn’t come a second time. And, as times change, it becomes imperative to think about to what extent, and in which forms, it continues to be necessary.

The problem of art and of the artist is different from what it once was – it has another face now. Common people’s tastes have become much more changeable than before.

Art has become multi-faceted the world over. It’s more in the spotlight than it used to be. There’s been an awakening about it in European countries.

The poet Daud Haider, who was with us from the beginning of the Dynamic Art Movement, was, at the time of the twenty-fifth anniversary celebrations, visiting Calcutta and had put up in Annada Shankar Ray’s house. He had been banished from Bangladesh in 1974 [editor’s note: for a poem deemed blasphemous] and had moved first to Calcutta, and then to Berlin, where he’s been living since 1987. Hearing celebrations were imminent, he sent us a letter. I refer here to a section from it: ‘In the last ten years, I have seen many things happen in Europe. The Berlin Wall is a different matter. But walls are being painted in various cities. Poems are being inscribed upon alongside paintings. In Paris, Madrid, Denmark’s Copenhagen, Sweden’s Stockholm, and the Czech Republic’s capital Prague, people continue painting pictures on walls. Poetry isn’t being neglected either. In fact, people are painting on roads too. The Bangladeshi artist Ruhul Amin Kajol is in the Guiness Book of World Records for painting on the streets of Madrid. Ashit Paul was the inspiration behind this. I’ve said this in many talks I have given in European cities. Some audiences have, astonished, made note of this. Just as an artist had begun to paint upon the wall of an old house in Switzerland’s capital city, Bern, I had said to everyone there that the artist Ashit Paul of Calcutta had opened people’s eyes twenty five years ago by painting on walls. On hearing this, Picasso’s son Claude wanted to know if Paul was still active. He said, Please tell him to give the movement even greater momentum. Paloma, Picasso’s daughter, said the same thing in Berlin.’ Daud was banished from Bangladesh for offending religious sensibilties, similar to what happened later to Taslima Nasreen. Our writers and artists looked after them both with great regard when they lived for a while in Calcutta.

I am, for now, bringing to an end what I’ve written on the Dynamic Art Movement. A lot of people want to know about it in greater detail; I may return to it in the future. The Hungry Generation, Kobita, Krittibas, Ghanti ki Kobita, Dainik Kobita, Third Theatre – all of these magazines and movements will leave their mark on art and culture.

Rabindranath realised that we needed to know about developments in art across the world if Indian art were to flourish. He used to fear our parochialism would be the biggest impediment to our own advancement.

Many people were involved in our movement, and I haven’t been able to mention everyone – but I must mention some who left us before they should have, those whose goodbyes were final: they’re on my mind every moment.

Papiya Chakraborty went on to marry Ashish; she was a good artist herself, and worked for the radio. Suddenly, one day, we heard that she had died in an accident on Saraswati Puja. There’s been a lecture in her memory for many years now, arranged by Ashish.

The young poet Dipankar Saha, who was part of our movement while he was studying in Calcutta University. He was from Agartala, and shared many of our dreams. He had a brain tumour, and couldn’t fight it beyond a point.

Tapan Ghosh, a successful doctor. He was a leading paediatrician. He had treated many poets and artists pro bono. He died unexpectedly because of an increase in red blood cells in his blood.

Dhurjati Chanda, poet, was with us from the movement’s inception, and used to publish a periodical with a beautiful name ‘Ebong [etcetera]’; he met Nileema at the domed gallery and later married her. We heard, at one point, that he was no more.

Ranjan Purakayastha, poet, who became a very close friend of mine. After being a part of my life for many years, he died suddenly. That kind of person is hardly to be found anymore – a lovely man.

Sarada Pal: she was with us from the start. She quickly became everyone’s favourite Khukudi. She left us before her time.

There was a boy called Shital whom Kallol had brought along; he used to stay in a hostel and got deeply involved with us. I heard he was standing at a train’s entrance one day, and his head hit a light-post while the car was moving.

We lost Sounak Lahiri only the other day. He enthralled audiences with poems on so many occasions.

Ajit Pandey came to the gallery as long as it was extant and charmed us with his singing. He’s no longer with us.