Reproduced from Harvard Museum Blog.

What about Criticism?: Blanchot’s Giant-Windmill

PETER D. MCDONALD

In his mission statement, Amit Chaudhuri identifies what he calls ‘market activism’ primarily with publishers and literary agents, or, perhaps more specifically, with the large publishing corporations and ‘super-agents’ who began to reshape the literary world during the early 1990s.1 But he also looks briefly askance at universities in order to point out an implicitly fatal coincidence. By the time publishers and agents were turning the language of critical evaluation into a marketing tool, creating among other things a new mass-market genre called ‘literary fiction’, ‘most literature departments’ had, he comments, ‘disowned’ that language altogether, shying away from a word such as ‘masterpieces’ and even withdrawing from ‘the literary itself’. I am assuming he is, in the latter case, thinking about the rise of cultural studies, which in some of its more militant formulations did discard Shakespeare for supermarkets. In the former case, I imagine he is referring to the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, which became something of a critical orthodoxy during the 1980s and 1990s.2 On this last issue he has the support of the fictional author-figure in J.M. Coetzee’s Diary of a Bad Year (2007). At one point, JC, as this figure is called, observes that students of the ‘humanities in its postmodernist phase’ were ‘taught that in criticism suspiciousness is the chief virtue, that the critic must accept nothing whatsoever at face value’.3 Unlike the more militant forms of cultural studies, this left room for Shakespeare but only as an object of wary scrutiny, not as a canonical master of his medium.

As I take it, then, the question of ‘literary activism’ – What is it? What are its goals? And so on – can be posed not only against the background of ‘market activism’ but against what Coetzee’s author-figure also calls ‘the trahison des clercs of our time’;4 or what Chaudhuri calls, no less forcefully, the betrayal of ‘the literary itself’ by ‘most literature departments’ – JC is invoking Julien Benda’s attack on party intellectuals of the left and the right in La Trahison des Clercs (1927).5 As I am a salaried academic – perhaps even a latter-day clerc in JC’s sense – I’ll focus on this last issue in the context of contemporary debates about the university.

I should make it clear from the outset that while I recognise and deplore the betrayal Chaudhuri identifies, I was not unsympathetic to the cultural turn in the 1990s, a position I still maintain. True, it had many crudely anti-literary advocates – the New Zealand-born academic Simon During was among the most prominent – but there were others, such as the American professor of English and comparative literature Bruce Robbins, who had a more nuanced sense of the stakes involved.6 As Robbins recognised, the problem was not so much literature per se, but what he called ‘traditional literariness’, a notion he understood primarily in relation to American New Criticism – he served his academic apprenticeship at Harvard in the late 1960s and through the 1970s, when this was still very much in its heyday.7 At the heart of this critical enterprise, as Robbins saw it, was a ‘nonpragmatic, non-instrumental’ formalism, which all too often reduced the experience of literature to a matter of ‘inconsequential privacy’.8 Under the aegis of New Criticism, ‘traditional literariness’, he argued, put ‘a safe distance between itself and officialdom, or the public’, thereby justifying the turn to cultural studies, which he saw as a more ethically and politically engaged form of enquiry.9 So, for some advocates of cultural studies, the issue was not so much ‘the literary itself’ but versions of literariness associated with some influential but questionable styles of criticism.

Two examples of what might count as ‘literary activism’ are highlighted in Chaudhuri’s prefatory note and elsewhere in this collection of essays: Derek Attridge’s critical championing of Zoë Wicomb, and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s nomination as Oxford Professor of Poetry in 2009 in which Chaudhuri and I both played a part. My understanding is that Chaudhuri drew attention to these cases because both were clearly acts of critical evaluation, albeit of a very particular kind. If they expressed a firm commitment, even endorsement, they did so without laying claim to the megalomaniacal hype with which such endorsements are too often associated. While Attridge was not interested in holding up Wicomb as an exemplar of some or other ‘new literature’, we in Oxford were not concerned about winning the election. The point in both cases was to ‘fashion an event’, to shift the terms of critical debate, and – most importantly – to do so in a way that was in keeping with the ‘desultory’ character of the literary itself.10 I take this last point to be central. It suggests that what might be most interesting about literature, as a mode of public intervention, is that it is itself, or at least in its most compelling forms, indifferent to power. Even when it takes on other more potent forms of public discourse, whether political, religious, journalistic, or whatever, it does so without claiming rival authority for itself – without, that is, getting caught up in the game of ‘market activism’. What it does is open up a space in which all kinds of authority and definitive forms of language are put in question, including its own – hence Chaudhuri’s claim about ‘the strangeness of the literary’.

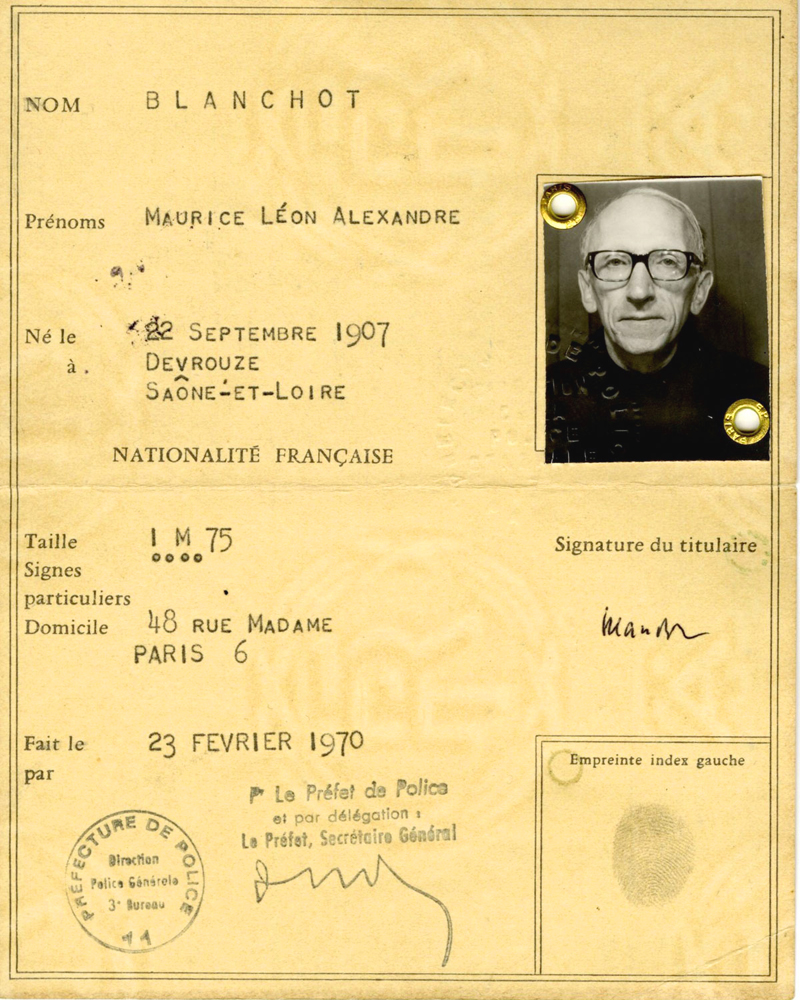

So for me the question is: how do we fashion a critical language equal to this strangeness? Clearly neither the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, nor ‘traditional literariness’ are going to be much help. If the former is too preoccupied with its own claims to power, the latter is too keen to see literature as a safely sanitized aesthetic zone, above or at least protected from the public fray. I’d like to suggest that a largely forgotten short essay by the twentieth-century French critic and writer Maurice Blanchot offers an alternative way forward. Before I turn to the details of the essay itself, however, I should say something briefly about its provenance.

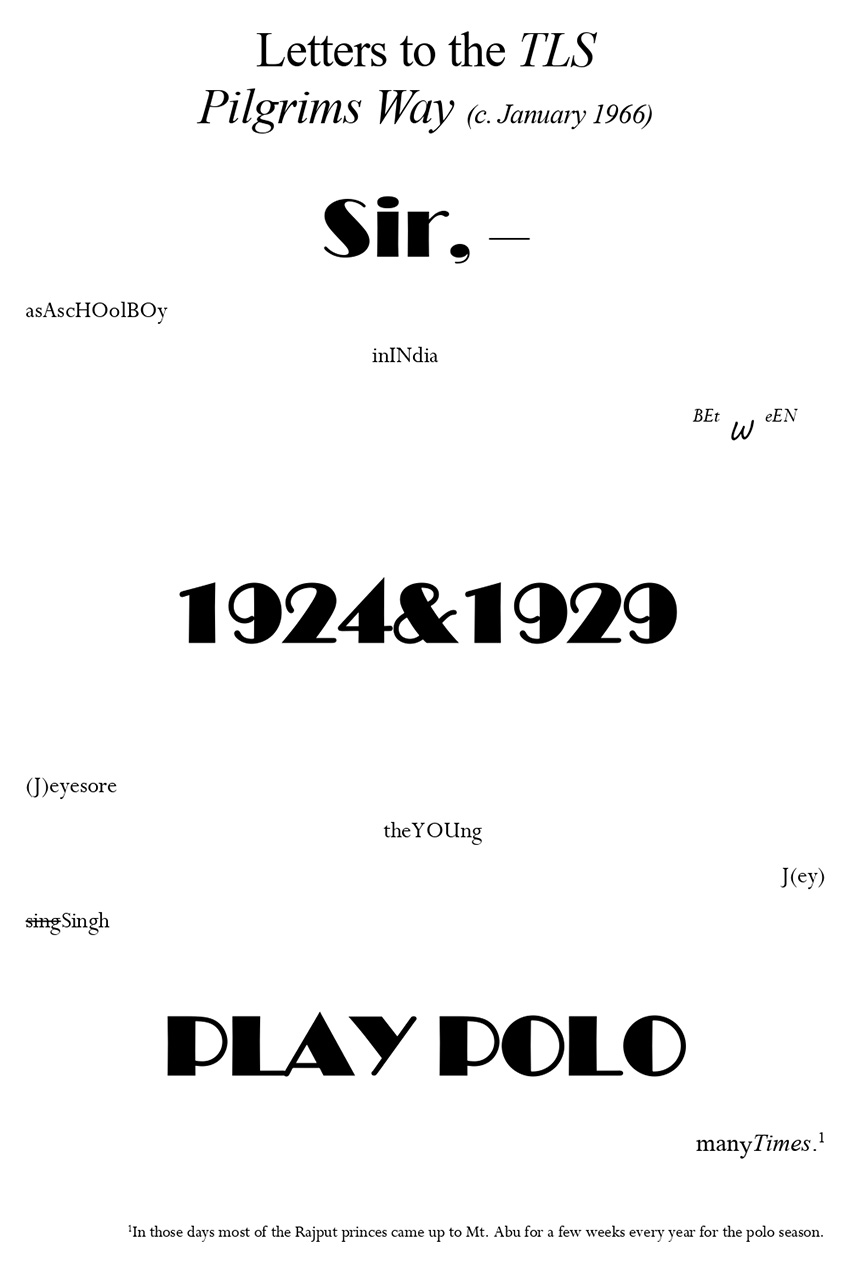

It first appeared in French in the journal Arguments in early 1959 under the title ‘Qu’en est-il de la critique?’ (or ‘What about criticism?’).11 Arguments was a relatively short-lived forum for a dissident group of Marxists and fellow travellers who broke with the still strongly Stalinist French Communist party (PCF), following Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in 1956, and with the orthodoxies of Marxist criticism. The editors angered György Lukács, for instance, by insisting on translating and publishing his early work, which did not observe strictures of dialectical materialism. They also published Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, and Blanchot, among others. Some forty years later the essay resurfaced in English, translated by Leslie Hill, in the Oxford Literary Review under the rather more forbidding, and less interrogative, title ‘The Task of Criticism Today’.12 Though very different to Arguments, the Oxford Literary Review is not quite what it seems: the title was intended as a joke. It has only a tenuous connection to Oxford University, and it does not publish or review original literature. Founded in 1977, it has during the past three decades made a name for itself as the primary platform for French deconstructive thought in the English-speaking world.

Why dwell on these details? If there is one lesson from cultural studies worth reaffirming, it is that we cannot talk about fashioning a critical language without considering the media and institutions through which that language might find its way into the public domain. In this regard, these changing forums tell their own story. At one level, they reflect the ongoing structural transformation of the public sphere and suggest something about the increasing dependency of criticism on the university. Arguments, which served as a model for the British New Left Review (founded in 1960), was a little magazine of sorts, though it had at its peak around 4,000 subscribers. Published by Editions de Minuit, the French resistance imprint, it created a forum for autonomous debate ‘situated in the space between political activity and intellectual work, Marxism and that which escapes it’, as the founding editor Edgar Morin put it.13 Like Blanchot, many of its contributors were what we might now call public intellectuals with no direct links to universities. By contrast, the Oxford Literary Review, for all its own doubts about the modern university, is run by salaried academics essentially for salaried academics and published by Edinburgh University Press. It has never had more than 420 subscribers.14 At another level, these changing forums also track the various moments and contexts through which Blanchot’s question ‘What about criticism?’ has moved in the past half century or so. Here I am thinking not only of the move from intellectual arguments within Parisian journals to academic debates within the university, but from dissident French Marxism in the late 1950s to what came to be called ‘Theory’ during the 1980s and 1990s, and, of course, to our own debates about ‘literary activism’ today.

There is one further thing I need to do before I turn to the details of the essay. For reasons that will, I hope, become clear, I am at this point going to have to dispense with the fiction of writing in only one voice. I know that the essayistic monologue is de rigueur for academics generally, but, given my own conflicted thoughts about the issues under discussion, I’m going to have split myself in two. For ease of identification, I’ll call the first voice Don Q, and the second Sancho P.

DON Q: To my mind one of the most compelling things about Blanchot’s essay is its bracingly sardonic tone. After describing the critic as ‘this mediocre hybrid, half-writer, half-reader, this bizarre person who specialises in reading yet can read only by writing’, he remarks that when ‘we subject criticism to serious scrutiny, we get the impression that there is nothing serious about the object of our scrutiny’.15 In part, this is because criticism, at least as he saw it in France in the late 1950s, depends for its very existence on ‘two weighty institutions’: ‘journalism’ and the ‘academy’ (i.e., the university).16 Though often accused of being highmindedly philosophical, Blanchot was in fact always alert to the real-world dynamics of institutional power and, in this case, to its many ironies. Criticism’s dependency on ‘journalism’ and the ‘academy’ was particularly hapless, he felt, because neither really shares its concerns, ‘each having a firm direction and organization of their own.’17

This unfortunate institutional predicament had the further consequence of exposing the fragility of criticism’s authority. Since it produces neither the ‘scholarly knowledge’ of the university, which Blanchot believed has the virtue of being ‘solid and permanent’, nor the ‘day-to-day knowledge’ of journalism, which may be ‘trivial and short-term’ but is at least ‘expeditious’, it is, like a perpetual teenager, never quite sure about its status or function. Perhaps, Blanchot wondered, it might find a place for itself as a somewhat needy mediator between these institutions and kinds of knowledge, an ‘honest broker’ linking scholarship to the everyday concerns of journalism and the wider public?18 Or maybe it could take on a role as an advocate of ‘higher values’?19 In this last scenario, he envisaged the critic achieving some status as ‘a spokesman applying general policy’.20 It is difficult not to think he had party clercs like the later Lukács in mind here – though, if we read this in more self-critical terms, then he could well have been thinking of his own earlier incarnation as a French nationalist clerc of the 1930s. Yet, if this is the ‘task of criticism’, he wrote, it ‘hardly amounts to much’ – ‘it could even be said to amount to nothing at all’, since all clercs require is ‘a degree of competence, a talent for writing, a willingness to please and a measure of goodwill’.21 Again, read not just as a jibe at party intellectuals of all kinds but as the profession of an ex-clerc, this carries some additional weight.

Having sketched the unpromising institutional conditions of criticism in general terms, Blanchot then paused briefly to reflect on what we might too succinctly call the orthodoxies of 1950s French Marxism, although he never named them as such, according to which literature had to be read and critiqued as a symptom of history, specifically history as understood in French Marxist terms. With what is perhaps too much politesse – he was well aware of how this would play outside the pages of a dissident journal such as Arguments – he acknowledged the force of this dominant critical tradition, but claimed that criticism ‘has no authority to speak seriously in the name of history’, which has ‘taken shape within disciplines that are more rigorous, more ambitious too’.22 The task of showing ‘how a literary work relates to history at large or to its own evolution’ could be left, he suggested, to ‘the science of historical interplay’, to which he added wryly and in parenthesis ‘(if it existed)’.23 Again, it is difficult not to think he had not just the clercs of the PCF but the later Lukács in mind.

So if criticism cannot achieve any distinction as a mediator between journalism and the university, as an advocate of ‘higher values’ serving one or another set of political interests, or as a branch of the ‘historical sciences’, then what is left for it to do?24 Characteristically, in working his way towards his own more affirmative answer to this question, Blanchot turned what he had just identified as criticism’s weakness into its strength. ‘A derogatory view like this is not offensive to criticism,’ he insisted, ‘for criticism readily welcomes it, as though, on the contrary, the very nullity of criticism were its most essential truth’.25

In one of many attempts to characterise this ‘nullity’, and to make a virtue of it, he observed: ‘Criticism is nothing, but this nothing is precisely that in which the work, silent, invisible, lets itself be what it is’.26 Or, in a more extended formulation:

Criticism is no longer a form of external judgement which confers value on the literary work and, after the event, pronounces on its value. It has become inseparable from the inner workings of the text itself, it belongs to the movement by which the work comes to itself, searches for itself, and experiences its own possibility.27

Crucially, for Blanchot, this kind of criticism, which follows no prescribed protocols, effectively inventing itself anew in the face of every new work, or act of reading, is equal to what Chaudhuri calls the ‘strangeness of the literary’. As Blanchot put it: ‘precisely because, modestly, obstinately, it claims to be nothing, criticism ceases to distinguish itself from its object, and takes on the mantle of creative language itself, of which it is, so to speak, both the necessary actualisation and, more figuratively, the epiphany’.28 It is difficult – and don’t forget I’m still speaking as Don Q – to imagine a more compelling antidote to the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, which knowingly stands apart from the work assured of its own mastery, and to the ‘traditional literariness’ Robbins identified with American New Criticism, which is no less confident about its own formalist aesthetics and capacity to separate literary from political interests, or vice versa.

SANCHO P: This is all well and good but the world has moved on since 1959. For one thing, criticism, no less than creative writing, is now almost wholly dependent on the university for its survival. We no longer live in a world in which a critic such as Roland Barthes, or indeed Blanchot, could make his name in a newspaper. When it is not preoccupied with anxieties about its own potential extinction in the digital age, journalism today is at best a forum for reviewing and celebrity author gossip, at worst an instrument of ‘market activism’. And, when it comes to criticism, it is not too far-fetched to argue that it has become an almost wholly self-enclosed professional discourse, the kind of writing produced solely for the advancement of academic careers. The fact that Blanchot’s essay moved from Arguments in 1959 to the Oxford Literary Review in 2000 is just one small instance of this larger trend. In the face of this significant reality, as even the most rudimentary sociological analysis of the academic world would show, treating ‘the very nullity of criticism’ as its ‘most essential truth’ is unlikely to get much traction. Contemporary clercs, in JC’s sense, even those who eschew the easy exaltations of suspicion or the onanistic joys of aesthetic pleasure, are under too much pressure to build professional networks, perhaps even empires, founded on transferable methodologies and generalisable styles of reading, and to champion ‘new literatures’, or new categories such as ‘World Literature’, in short, to chase the next professionally saleable and reifiable (or is it REFable?) idea.

Yet professionalisation is perhaps the least of the difficulties a Blanchot-style critic would face today. If we consider the vulnerability of the contemporary university itself as a sponsor of humanistic study, let alone criticism, then the situation appears even more unpromising. As the American scholar Jim Collins has noted, the ‘massive infrastructural changes in literary culture’, which, like Chaudhuri, he associates primarily with the ‘conglomeration of the publishing industry’ since the 1990s, coincided with a significant shift in ‘taste hierarchies’, among which he includes ‘the radical devaluation of the academy and the New York literary scene as taste brokers who maintained the gold standard of literary currency’ and ‘the transformation of taste acquisition into an industry with taste arbiters becoming media celebrities.’29 He had in mind ventures such as Oprah Winfrey’s enormously influential book club. To this I would add the rise of online communities and social media as forums for literary discussion, which bypass traditional reviewing and more or less ignore, if they are not actively hostile to, academic criticism. In this context, it is difficult to see what weight criticism, defined in Blanchot’s terms, can possibly carry. At best, it would generate just one more opinion in an ocean of digital opinions, at worst it would be discredited in advance as the opinion of a professor nostalgic for the producer centred age of print and a time when the university was looked upon as a custodian of one or another great tradition.

To the seismic effects of these broader changes in the media environment we have to add the simultaneous reconfiguration of the university itself at the hands of various governmental authorities in thrall to the orthodoxies of statist neoliberalism (Stalinist Thatcherism?) and its forms of ‘market activism’. For a pithy summary of this history, we can return to JC, Coetzee’s author-figure in Diary of a Bad Year.

What universities suffered during the 1980s and 1990s was pretty shameful, as under the threat of having their funding cut they allowed themselves to be turned into business enterprises, in which professors who had previously carried on their enquiries in sovereign freedom were transformed into harried employees required to fulfil quotas under scrutiny of professional managers. Whether the old powers of the professoriat will ever be restored is much to be doubted.30

With the future of humanistic enquiry in mind, JC then suggests that, if the ‘spirit of the university is to survive,’ professors may have to become like the ‘dissidents who conducted night classes in their homes’ in the ‘days when Poland was under Communist rule’.31 This was not just JC’s rather pessimistic opinion in a work of fiction. For those interested in ‘the strangeness of the literary’, particularly as it pertains to the question of authority, Coetzee said much the same thing in his own person in the foreword to a recent collection of essays on Academic Freedom (2013).32 For all these reasons – and of course I’m still speaking as Sancho P – I suspect criticism, as Blanchot understands it, is going to have to become a subject for ‘night classes’, given off campus, and published in dissident blogs or the online equivalent of Arguments.33

DON Q: This is all far too gloomy.

Professionalisation is a fact of modern life and, besides, in any impartial comparisons with bankers or politicians, the professoriat comes out rather well. And no matter how the media environment changes, or what governments do to universities, you can always rely on younger people not to accept reality as the previous generation attempted to define it, and, in my experience, they do not seem to have lost the desire to ask serious questions about themselves and the cultures they inhabit.

Moreover, your pessimism rests on a false assumption about Blanchot’s contemporary relevance. Far from being a hopelessly dated anachronism, he speaks directly to many of our own concerns. In the conclusion to the essay I have been discussing, for instance, he addresses Chaudhuri’s observation about literature departments disowning the language of evaluation. ‘The complaint is sometimes made that criticism is no longer capable of judging,’ he says.34 Yet, reinforcing his underlying case for a self-eff acing style of criticism without protocol, he insists: ‘It is not criticism which lazily resists evaluation.’ Rather it is the literary work that ‘withdraws from evaluation because it seeks to affirm itself in isolation from all value’; that is, from all established protocols of value, which too many guardians of the literary devote themselves to upholding, or, for that matter, any pre-given political values of the kind Benda’s overly compliant clercs championed.35 Again, once criticism opens itself up to the demands of the work, once it ‘belongs more intimately to the life of the work’, then ‘it experiences the work as something that cannot be evaluated’.36 For Blanchot, this is not a matter of ‘inconsequential privacy’, to recall Robbins’s phrase, nor is it simply about literature or criticism. It is ‘closely related to one of the most difficult, but most important tasks of our time’: ‘The task both of preserving and of releasing thought from the notion of value, and consequently opening history up to that which, within history, is already moving beyond all forms of value and is preparing for a wholly different – and still unpredictable – kind of affirmation’.37 In the first, untranslated version of the essay, he spelt out what this affirmation might mean in more detail, linking it via a series of provocative questions to ‘a neutral and impersonal power, beyond any distinct interest, any definitive word (parole déterminée) and to a ‘profoundly indeterminate movement’ expressing the ‘future of communication and communication as the future.’38

Such comments about disinterestedness, the unpredictability of history, the transvaluation of values, and the possibility of a radical openness to the future clearly had a special resonance in the pages of a dissident French Marxist journal in the late 1950s and another kind of resonance in an academic journal devoted to French deconstructive thought in 2000. I think they have as much to say to our own concerns about ‘literary activism’ today.

SANCHO P: You sound like someone I have read about who believed, madly and incorrigibly, ‘that, by the will of heaven, I was born in this age of iron, to revive in it that of gold, or, as people usually express it, “the golden age”’.39

DON Q: I read that story myself and couldn’t help noticing that a certain Sancho Panza plays a curiously double role in it. Yes, he mocks the engaging but easily deluded Alonso Quixano, pointing out that the giants he claims to see are in fact windmills. Yet he also helps him along in his amazing adventures and so keeps the story, and Alonso’s efforts to revive the ‘golden age’, going.

1. For an informative academic study of these new circumstances, see John B. Thompson, Merchants of Culture (2010; Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012).

2. For my own further take on this, see Peter D. McDonald, ‘Ideas of the Book and Histories of Literature: After Theory?’, PMLA (January 2006), pp. 214-228; for a recent account, see Rita Felski, The Limits of Critique (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2015).

3. J.M. Coetzee, Diary of a Bad Year (London: Harvill Secker, 2007), p. 33.

4. Coetzee, Diary of a Bad Year, p. 33.

5. Coetzee, Diary of a Bad Year, p. 33, and see Chaudhuri’s prefatory note to this collection, p. 3.

6. For During’s views as one of the chief proponents of cultural studies, see his introduction to The Cultural Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 1993), and ‘Teaching Culture’, Australian Humanities Review, August 1997, pp. 1-7. For his return to the literary, see Against Democracy: Literary Experience in the Era of Emancipations (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012).

7. Bruce Robbins, Secular Vocations (London: Verso, 1993), p. 110.

8. Robbins, Secular Vocations, p. 110.

9. Robbins, Secular Vocations, p. 116.

10. Chaudhuri, mission statement.

11. Maurice Blanchot, ‘Qu’en est-il de la critique?’, Arguments, Jan-Feb 1959, pp. 34-37. A revised version subsequently appeared in Maurice Blanchot, Lautréamount et Sade (Paris: Minuit, 1963), pp. 9-14.

12. Maurice Blanchot, ‘The Task of Criticism Today’, trans. Leslie Hill, Oxford Literary Review, 22.1 (2000), pp. 19-24. Hill based his translation on the revised 1963 version of the essay.

13. Edgar Morin, et al., Arguments 1 : La bureaucratie (Paris, Union Générale d’Editions, 1976), p. 11.

14. I am grateful to Professor Nicholas Royle, the current editor of OLR, for giving me these details. Personal correspondence, 17 October 2014.

15. Blanchot, ‘Task’, pp. 19-20.

16. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 19.

17. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

18. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

19. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

20. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

21. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

22. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 21.

23. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

24. Blanchot, ‘Task’, pp. 19, 21.

25. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 20.

26. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 21.

27. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 23.

28. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 22.

29. Jim Collins, Bring on the Books for Everybody (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 7-8.

30. Coetzee, Diary, p. 35.

31. Coetzee, Diary, p. 36.

32. See John Higgins, ed., Academic Freedom (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2013), pp. xi-xv.

33. Coetzee, Diary, p. 36.

34. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 23.

35. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

36. Blanchot, ‘Task’.

37. Blanchot, ‘Task’, p. 24.

38. Blanchot, ‘Qu’en est-il de la critique?’, Arguments, p. 37.

39. Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, trans. E.C. Riley (Oxford: World’s Classics, 2008), p. 142.

Peter D. McDonald is Professor of English and Related Literature at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of St Hugh’s College. His principal publications include The Literature Police: Apartheid Censorship and its Cultural Consequences (Oxford, 2009, see also theliteraturepolice.com), and Artefacts of Writing: Ideas of the State and Communities of Letters from Matthew Arnold to Xu Bing (Oxford, 2017; see also artefactsofwriting.com).

This essay was originally presented at the inaugural symposium in Calcutta in December 2014. It was collected with other papers in a volume called Literary Activism: A Symposium, edited by Amit Chaudhuri and published in 2017 by Oxford University Press and Boiler House Press.