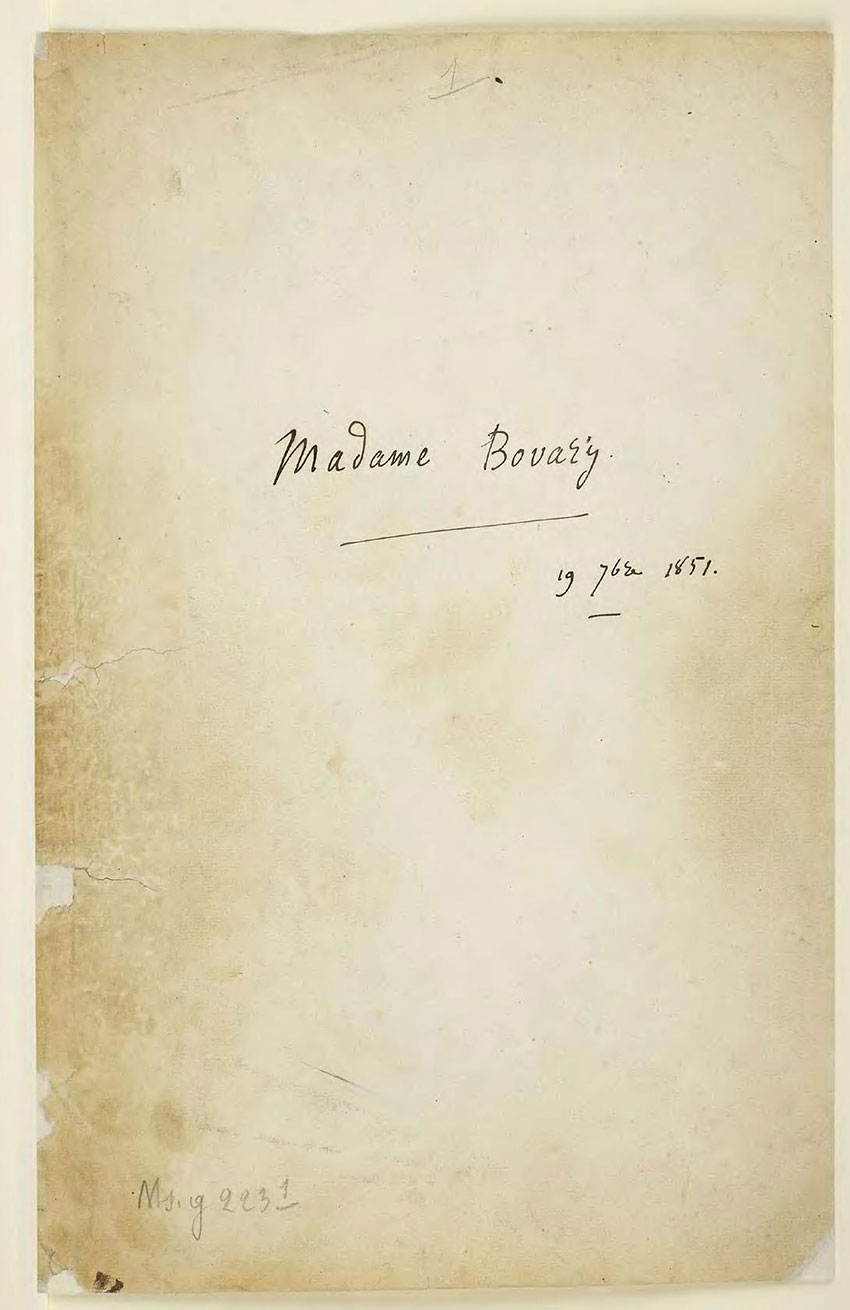

Madame Bovary, Manuscript page (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Madame Bovary and the Impossibility of Re-reading

Anjali Joseph

The first time I read Madame Bovary I was fourteen or fifteen. My family lived in England; at school I was learning French. Denise King, my French teacher, lent me her copy of the book, which was the one she’d used in university. I think it was a Gallimard paperback, but not a pocket edition. It had a primrose yellow cover with no picture. The paper was thick. Denise, as an undergraduate, had looked up all the words she didn’t know, and written the English in the margin. The novel is not written in very complicated language but it was a stretch for me at that point. I wasn’t very comfortable with the past historic tense which is usually only used in written French.

The reward for wading through the book was a story about a depressing guy named Charles in rural nineteenth century Normandy. He has a miserable childhood, a depressing time in school, and plods his way through medical school to become a surgeon. Then his mother gets him married to an older widow who’s supposed to be rich, but turns out not to be. The widow is also very depressing. One night Charles is called to treat a farmer’s broken leg and he rides into the countryside. The farmer is a widower and has a young daughter, Emma, who’s educated and pretty. She’s bored, Charles gets a crush on her, and after a few months his depressing older wife dies and he gets to marry Emma. Then the novel is about Emma, who is also depressed being married to Charles because he’s not very bright or charming or good looking or sophisticated or well dressed, and she’s read a lot of novels and was hoping for something better. They move to a different small town and have a kid, and she spends her time thinking about having a love affair, and has not one but two, each of which is more depressing and damaging than the last, and she buys a lot of stuff from a door-to-door salesman and gets into debt and tries to run away with one of her boyfriends, who ditches her, and she ends up committing suicide. And Charles is heartbroken.

When I got to the end of the novel I was quite angry – mostly with Flaubert, a little bit with my French teacher, and definitely with life. As though it wasn’t bad enough that I was stuck in a small town in the middle of England, always feeling cold and trying to lean against a radiator that had apparently been turned off some time earlier, just waiting for enough years to pass till I could leave and go to college – on top of that I had to read this quite sarcastic book about a person stuck in a small town daydreaming of a better life, all of which had gone terribly wrong.

A few years passed – not as painlessly as that clause implies – and I was at college reading for an English degree. You had to do one paper in a foreign language. My French was quite good by this point, so I was in a class where we studied French verse and our set text was Flaubert’s book of three short stories, called Three Stories. Eric Griffiths, who taught the class, decided we should also read Madame Bovary. I went to Heffer’s across the street from college and bought my own copy of the book. It was a paperback and had a still from the Claude Chabrol film, showing the actress Isabelle Huppert playing Emma. And we sat on sofas in Eric’s rooms and learned why Madame Bovary was a great novel.

I was three years older than the first time I’d read it, and now I wasn’t stuck in the same provincial town. So I could begin to appreciate the novel’s apparently cruel humour. In the first chapter, Charles is fifteen and he arrives at a new school. Everything about what he is wearing is wrong – the school is in Rouen, the main town in the province, but he looks like a country boy. His jacket is too small, his red wrists are visible, his breeches are too tight, his shoes aren’t properly shined and there are nails in them. He sits down while the lesson is going on, but unlike the rest of the class who chuck their hats on the floor as soon as they sit down, he is holding his hat. And his hat, his school cap, is a terrible hat. This is how it’s described:

It was a piece of composite headgear, in which were mingled elements of a hunting cap, a Russian fur hat, a bowler, a sealskin hat and a cotton nightcap, one of those poor things, in fact, whose silent ugliness is as profoundly expressive as the face of an idiot. Ovoid, and reinforced with stiffeners, the hat began with three round pudding-like lumps; then, alternately and separated by a red ribbon, patches of velvet and rabbit skin; after that a bag-like part that finished in a rectangular cardboard shape covered with elaborate braiding from which, at the end of a long and overly thin thread, hung a little golden fabric cross, in the manner of a seed. The cap was new; its visor gleamed.

You only have to imagine yourself back in school to realize that this is not a hat: it’s a punishment. It’s also an apparently precise but absurd description in the sense that it’s almost impossible to imagine a costume designer, for example, being able to construct a hat exactly like this. The ways in which it is horrible might be too many and too fluid to translate into a physical object. Not only is Charles wearing this awful hat but then he drops it, and everyone in the class laughs at him. This is his first day in school. After that, the narrator says, ‘By working hard, he managed to maintain a position around the middle of the class.’ That is funny, just like the hat episode is funny, but in a horrifying way, which reminds me of Laurel and Hardy or Charlie Chaplin films. When I was in school in Bombay, we were sometimes shown silent comedy films as a treat, and the entire class would watch Stan Laurel getting beaten up, or something awful happening to Charlie Chaplin. Everyone would laugh till tears came out of their eyes. I remember going to see some Charlie Chaplin films at Eros Cinema with my parents and grandparents. I was horrified at the things that happened to Chaplin’s character the Tramp, and even more horrified that everyone around me thought these things were funny.

The next period of re-reading Madame Bovary was after another decade, when I was writing my first novel. I read a lot of debut novels, and it is a debut novel of sorts, though Flaubert had also written and rewritten and rewritten a play, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, before his friends held what Americans call an ‘intervention’ and asked him to stop. This time when I was reading Madame Bovary I forgot about the plot, which wasn’t a surprise because I’d read it before. I only noticed the interesting ways in which it is an odd novel. There is a reasonable amount of plot, but the novel seems to have been written by someone who doesn’t care much for plot. Instead, the parts that stayed with me were the aleatory parts, the supposedly random things. One incident I remember is how, when Charles is riding through the snowy winter night to visit the farmer whose broken leg he will set, and whose daughter he will marry, the narrator observes that it is so cold outside that small birds in the branches of the trees they pass are fluffing out their chest feathers. It’s a detail that makes you wonder whether Charles himself can perceive it as he rides past; if not, who is the narrator who notices such things? If the events aren’t the real focus, what is the real story of the novel?

There are many other such moments. There’s one which describes Charles’ early education, before he goes to school. The village curate is supposed to teach him but this takes place in an ad hoc way:

Lessons took place at stolen moments, in the vestry, standing up, in a hurry, in between a christening and a funeral; or the curate sent someone to call his pupil after the Angelus, when he didn’t have to go out. They went up to his bedroom, they settled down: the midges and moths revolved around the candle. It was warm, the child was falling asleep; and the man, drowsing with his hands on his belly, in no time was also snoring, his mouth open.

The novel is narrated mostly in the past tense, but in these moments, Flaubert uses the imperfect, which encompasses a few related English usages: was doing, used to do, would do. All of these come under the imperfect in French. Above I’ve translated ‘les moucherons et les papillons de nuit tournoyaient autour de la chandelle’ as ‘the midges and moths revolved around the candle’ but it could equally be translated as ‘used to revolve around the candle’ or ‘would revolve around the candle’ or indeed ‘were revolving around the candle’. Reading a little description like this feels like looking into a window and seeing the figure in a short animation performing the same action over and over again. Like a GIF. And the moment described is not particularly elevated: a child and a curate falling asleep over a lesson, but there is an effect of slow motion, and a beauty in the irrelevance and the slowing down that allows us to notice the light, the insects, the sense of presence that isn’t something the characters seem to notice, and doesn’t seem to be something they emanate. But it’s there, nonetheless. The novel is filled with such moments – there’s another one where Charles is a medical student living in an attic room, eating poorly, and in the evening watching domestic servants in a back lane near a canal, washing clothes or playing at shuttlecock, a kind of badminton. In a way it’s not a novel about human characters at all: it’s a novel of objects and insects and sunlight and birds, of stains, or habit and repetition. And though the characters in the novel live straitened lives, lives in which there isn’t much pleasure or satisfaction, the phenomenal world around them is generous with beauty. Maybe beauty is the way the world expresses love?

The title of this talk is ‘Madame Bovary and the impossibility of re-reading’. I came up with the title some time before I wrote the talk, and when I thought of the title I was thinking about the idea of re-reading. Also reassessing because Madame Bovary is a novel that was such an important novel to me, and yet which in many ways I didn’t like at all at first. I don’t know how much I like it now. I admire it, I love it, I still find it quite an uncomfortable experience to read it. Then, practically, it was kind of problematic to re-read the novel and I didn’t get through all of it. My own copy is sitting in a bookshelf in Pune and I forgot to bring it with me the last time I was there in November, even though I think I agreed to take part in this symposium maybe a little before that. So I looked online to see if I could order the book, and realized it would cost a lot to get it in India, so I downloaded it. I’m quite resistant to the idea of reading fiction on a screen, so it was a bit of an effort, and kind of a rupture not to return to the familiar paperback to re-encounter the novel. Also, – and this is the impossibility referred to in the title – I think there is a simple problem in the idea of re-reading, which is that it implies that the same two entities are meeting again, at a different point in time. That is sort of true, but in some significant ways not accurate. I am the same person, legally speaking and in conversation and in all sorts of other common sense ways, who had cold hands and feet and spent a lot of time in school in some corridor or other, huddling near a radiator that was always cold or nearly cold, wondering if it was time yet for me to leave Leamington Spa and go to university. But in other ways I’m not the same person, and I don’t even know how much I believe in the idea of a person, when experienced from the inside. There are continuities and discontinuities, and I think people can be more like clouds of energy and circumstances at a given moment than some sort of ongoing entity. So if reading is the intersection of a specific cloud of energy and concerns and daydreams with a text, naturally a later encounter of a subsequent cloud of energy, etc with that text might not feel like the second in a series of semblable things, it might instead seem to be, and actually be a different thing. This is an idea that has its echoes in empiricist philosophy of the 18th century, but also in Buddhism where one term for different ideas of the self is shunyata or ‘emptiness’.

There were recurring experiences that I related to the novel. Feeling cold, reading it on cold dark afternoons in different places – in Warwickshire, in Norwich, more recently in Guwahati in winter as the light died at three o’clock in the afternoon. I had this sense of myself sitting in different but similar rooms, feeling differently but similarly bored and interested and also feeling the imminent burden of coming up with something to say that someone else might find intelligent or worthwhile, but really not having the urge to do that. This experience seemed to have been going on for years, or maybe all the time, even as I thought I was leaving those rooms and going outside to do something else.

There was some consonance with the mood of the novel – a novel in which the principal character, Emma, longs for transcendence or to be transported from the banality of her life. The vocabulary she has for this longing is the vocabulary of romantic novels, so she thinks about things like balls at grand castles, or dashing noblemen who wear riding boots made of very soft, expensive leather. But there is nothing particularly ridiculous about being in one place and one situation and yearning to be elsewhere, or rather nothing particularly unusual about it. It’s a novel full of concrete details: for example, we know exactly what there is to eat at Emma and Charles’s wedding (including: four sirloins, six chicken fricassées, a casserole of veal, three lamb shanks, and in the middle of the table, a roast suckling pig flanked with four Andouille sausages with sorrel). The novel is also full of the heroine’s desires – boyfriend with soft leather riding boots, etc. But the actual moments of beauty and wonder are accidental, and although they might be available to the characters, the characters rarely seem to experience them. Emma does get to go to a fancy ball, after her husband treats the tenant of a local nobleman. The ball is a greatly anticipated event and when she is there, she looks at the other people there and there is the observation, ‘In their eyes could be seen the calm of passions which were satisfied day after day’. Even the reliability with which she envisages people having desires and fulfilling them doesn’t seem tedious to her, though perhaps it would to those people.

I was thinking about one of the places in which I spent a couple of years of cold afternoons reading and writing and staring out of the window wondering what was going on with my life. There was a period of a few months when I moved into a flat in Norwich, which was in the ground floor and basement of a square stone cottage that had originally been built for Huguenot weavers fleeing religious persecution in France. I moved in quite suddenly after breaking up with someone and spent a solitary few months in the flat before life seemed to resume. Recently I thought of that summer in a quiet moment, and what I’m going to describe as my soul – the quiet part of my mind, the witness – said Oh, that was a lovely time. And I thought, What? No, I was miserable. And then I had a disembodied view or perception of that period of time and realised that whatever I’d been doing – waking up, doing some yoga, writing a bit, cooking a bit, doing some laundry, reading, teaching, going for a run in the evening after it was dark, spending most of my time alone – all the time, something else had been present, and it was this witnessing quality, the soul if you like. I’d been miserable, but it hadn’t cared at all, because it didn’t have the same agenda as the everyday part of me. I could choose to be happy or desperately unhappy or bored and it didn’t mind; it was happy all the time anyway.

In Flaubert’s novel, Emma Bovary is not very successful at being happy. She tries very hard. She tries to be outwardly virtuous; she tries to be religious; she tries to be happy by falling in love; she tries to be happy by reading, and makes long lists of books she plans to read. But rarely does she seem to tune into the simple happiness that emerges from the novel’s quietest moments. Many of her strategies to achieve happiness are pitiable, because they are mechanical. Also, she’s unlucky – the people she falls in love with are unreliable, and she can’t manage to fall in love with the person who is reliable and does love her. Nonetheless, famously when a correspondent of Flaubert’s said Emma was a silly woman, Flaubert responded, ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi,’ I am Madame Bovary. Rodolphe, Emma’s first extramarital boyfriend, the one with the good riding boots, has a scene in which he’s writing her a goodbye letter, and he has a box of keepsakes given to him by women he’s been with, exactly such a box, in fact, as Flaubert himself had. No-one in the novel is particularly wise, but no one is dismissed. The repurposing of these different elements – of things that might be considered low art, or simply things that might be considered tawdry – and the rearranging of them into something else is a kind of time travel, a re-appropriation or a re-reading, and it struck me that it’s those journeys back to the fictional past, whether past encounters with a work of fiction, or with the fictions of one’s own past, even the fiction of having a past, that enable a different gaze to operate. This soul’s eye view isn’t without feeling, even if it has little to do with the emotional weather of everyday life. The feeling that it uses to reanimate the past is not sympathy or identification but compassion, and as that compassion touches the past, the past is released.

Anjali Joseph’s most recent novel, Keeping in Touch, was published by Context in India in 2021 and will appear from Scribe in the UK in 2022. She is interested in art that evokes wonder.