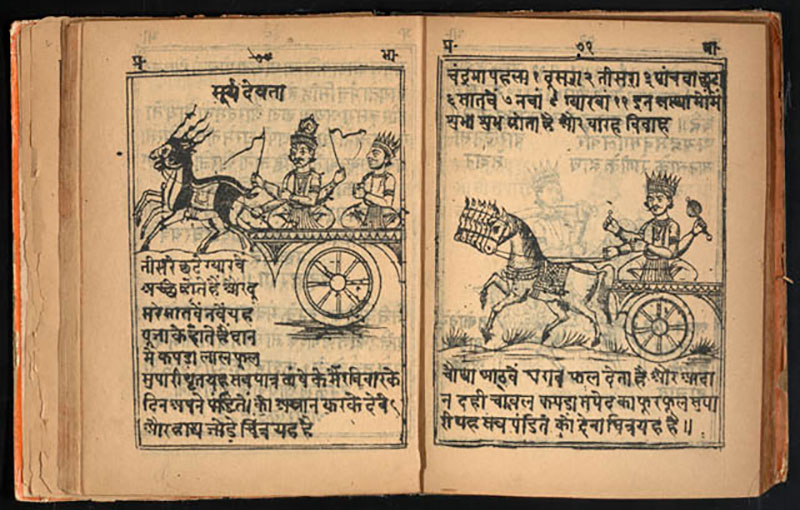

Two pictures of the sun god Surya in his chariot, Jwala Prakash Press, 1884. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Possible, not Alternative, Histories

A Literary History Emerging from Sunlight

Amit Chaudhuri

I’m looking back at the title to remind myself of what it is. ‘Possible, not Alternative, Histories’. I want to do something here that’s reckless because it’s very ambitious. I want to tell you about my reading. And, in the process, I wish to describe or allude to glimpses or hiccups or revisions that are germane to a discussion on reassessment. And also talk about not only my history, but a possible literary history. By ‘possible’ I don’t mean a history that doesn’t exist, but possible ways of looking at history. I also wish to distance myself from the term ‘alternative history’: it feels exhausted. Certainly, if somebody of my ethnic and cultural background spoke about it, they’d inevitably do so with a particular inflection and emphasis. I’m distancing myself from the idea of ‘alternative histories’ in order to enquire into what histories it might be possible to speak about and describe, and in what way.

In order to do this, one must first create and explore a space that one might call, for convenience’s sake, a ‘fictional’ space. This ‘fictionality’ facilitates a critique, a certain way of speaking, which wouldn’t be possible in a sombre piece of academic writing. Let me try to give you an example. I’m obviously not referring, when I say ‘fictional’, to writing about characters or telling stories. I mean a particular tone which you can’t reduce to irony, a tone that’s serious but at the same time indeterminate, and most profound when parodying itself. Borges was a great practitioner of this register; it’s moot as to whether his most significant critical insights occur in his mock-essays or in his essays proper. What is the difference between the first and the second? The instances of type 1 and type 2 that come almost randomly to mind from his oeuvre are ‘Pierre Menard, the author of the Quixote’ and ‘The Argentine writer and Tradition’. In ‘Pierre Menard’, the narrator points out that the eponymous author ‘did not want to compose another Quixote – which is easy – but the Quixote itself. Needless to say, he never contemplated a mechanical transcription of the original; he did not propose to copy it. His admirable intention was to produce a few pages which would coincide – word for word and line for line – with those of Miguel de Cervantes.’

Famously, this mock-narrator goes on to quote from Cervantes’s Don Quixote and then from Pierre Menard’s, to analyse their differences, and showcase the latter’s originality:

It is a revelation to compare Menard’s Don Quixote with Cervantes’s. The latter, for example, wrote (part one, chapter nine):

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counsellor.

Written in the seventeenth century, written by the ‘lay genius’’ Cervantes, this enumeration is a mere rhetorical praise of history. Menard, on the other writes:

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counsellor.

History, the mother of truth: the idea is astounding. Menard, a contemporary of William James, does not define history as inquiry into reality but as its origin…

The contrast in style is also vivid. The archaic style of Menard – quite foreign, after all – suffers from a certain affectation. Not so that of his forerunner, who handles with ease the current Spanish of his time.

The question of what gives to writing its modern or archaic or national characteristics comes up again in ‘The Argentine Writer and Tradition’, which, in the collection Labyrinths, is classified as an ‘essay’ rather than, as ‘Menard’ is, a ‘fiction’. Borges, here, makes a series of proclamations that distinguish him from his Argentine contemporaries and what they take to be the attributes of Argentine tradition. Among the better-known of Borges’s statements are these: ‘What is our Argentine tradition? I believe we can answer this question easily… I believe our tradition is all of Western culture, and I also believe we have a right to this tradition, greater than that which the inhabitants of one or another Western nation might have.’ In other remarks to do with the accoutrements of culture, Borges observes: ‘Some days past I have found a curious confirmation of the fact that what is truly native can and often does dispense with local colour… Gibbon observes that in the Arabian book par excellence in the Koran, there are no camels; I believe if there were any doubt as to the authenticity of the Koran, this absence of camels would be sufficient to prove it is an Arabian work’.

In both the fiction, ‘Pierre Menard’, and in this essay, Borges is at his most incisive in complicating the business of cultural and historical markers: he’s countering whatever it is we take to be the visible characteristics of a 17th-century Spanish work (Cervantes’s Quixote), a modern cosmopolitan text (Menard’s recreation of Cervantes’s novel), an Arab book (the Koran), and Argentine tradition. For Borges, there are no clear or definite features that proclaim a work to be Spanish or Argentine or Arabic, although each is definitely what it is because it’s Spanish or Argentine or Arabic. The register in which Borges explores this crucial insight (crucial to him and to the modern reader burdened with an over-determined notion of culture) is the register of ‘fictionality’: there’s almost no difference, tonally, between the invented scholar who presents the reader with Menard and the ‘Borges’ who begins his essay with ‘I wish to formulate and justify here some sceptical proposals concerning the problem of the Argentine writer and tradition.’ Who are we to take more, or less, seriously – the narrator of the Menard ‘fiction’ or of the essay? It’s worth adding here that, like Borges, Roland Barthes, too, is a writer whose work constantly inhabits the peculiar domain of fictionality; his provocations are enabled by tone: ‘we know that to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.’ It’s as wrong to take this sentence from Barthes as a simple declaration, to divorce it from its narratorial voice, as it would be to do something similar with any of the remarks in ‘Pierre Menard’. It’s appropriate that Barthes, like Borges, must invent a particular authorial register in order to debunk the notion of the author’s continuing, reassuring presence. To understand Barthes, you need to not only follow the argument, but to be alive to tonality. The tone of fictionality is not ironical; that is, it isn’t saying, ‘The opposite of what I’m saying is actually true.’ It’s disruptive. It allows the critic to become fiction-writer, and say what it isn’t possible to in academic writing.

*

My use of the word ‘possible’ is meant to gesture toward ‘fictionality’. The foundation and starting point of my account of certain shifts in literature in the last three decades refer to a particular turn in the 80s that affected us all. This turn was taking place on various levels, and I will restrict myself to two – the emergence of global novel, which encompasses what we used to call ‘magic realism’, novels to do journeys, novels to do with maps and the way cultures come together. The global novel proposed – I will use a perhaps harshly simplistic binary here – that a bourgeois domestic setting was integral to the conventional Western realist novel, and the non-Western novelistic imagination implied the emigrant’s journeys, border crossings, hybridity, and cartography. In other words, it’s difficult for the novels of ‘other’ cultures, generically speaking, to be about a bourgeois apartment. There was also talk of polyphony. Since the global novel opens on to multiple cultures and the manner in which they encounter and mingle with each other, it necessarily must be home to, and echo with, a hubbub of many voices. It will be polyphonic.

This wasn’t entirely unrelated to the new and largely unprecedented interest in philosophy at the time in literature departments. Here, a particular version of Derrida came into being, with a special style of interpreting his words, drawing attention to, for instance, his first work, Writing and Difference, where Derrida introduces the concept of play thus: ‘the absence of the transcendental signified extends the play of the signifier to infinity’. This unbridled incarnation of play segues, in fiction, into polyphony, which segues into the global novel of the journey: the extension of ‘play’ is also a new, political idea of narrative, a moving out from the shackles of realism into the limitlessness of globalisation and its historical precursor, the discovery of the New World (the subject of ‘magic realism’). I’m not saying that the philosophical and narrative turns are identical; but they come to occupy a particular tone – not only celebratory, but also triumphalist. With ‘play’ comes the notion of laughter. At this time, laughter emanates from Bakhtin too, with a specific political significance, a significance that immediately adheres to the ludic.

*

These developments announced the death-knell of the apartment, and the view from the window. All of that had been rendered imaginatively peripheral by the turn in the eighties. Oddly, inappropriately, it was at this time (1986, to be precise) that I began to think about moving from poetry to writing my first novel, A Strange and Sublime Address, which, in some senses, was a book about a house, and which I conceived of in spatial terms.

I want to give you a brief prehistory of this moment. I grew up in Bombay over the sixties and seventies. It was around 1978 that I became a poet-manqué; a modernist- manqué. There must have been a sizeable group of us from the middle and upper-middle classes who, in that period of hormonal transformation, were angst-driven. Theories of misery excited us; there was a buzz around two words in particular. The first was ‘existentialism’, a term that everybody was familiar with in Bombay, especially leading ladies like Parveen Babi and Zeenat Aman, who’d refer to it in interviews in magazines dedicated to film gossip. The other word was ‘absurd’. Of course, we understood these words in the light of teenage self-interest. Life was absurd for us as teenagers. We found a great deal of our experience fell under the purview of the existential, of absurdity: we tended to adopt, at once, an interior and metaphysical way of looking at the world. The moment we engaged with and immersed ourselves in this perspective and its language, we ceased to notice – simply weren’t interested in – the physical. I was oblivious, for instance, to Beckett’s humour. I was mainly concerned with the word that had associated itself with his oeuvre – ‘absurdist’, which sounded close enough to ‘absurd’. There were aspects of his theatre which appeared to confirm that, in the second half of the twentieth century, the contemporary imagination’s conception of both the world, stripped to its essentials, and of the proscenium was basically a post-holocaust landscape, minimal, with few physical or living details. Then there were the terms that Sartre had put out there: ‘contingency’, for instance, which led back urgently to Camus’s ‘absurdity’. Existence was contingent rather than pre-ordained; its lack of meaning or purpose made it ‘absurd’. The teenager in me would have seen this statement less as a celebration of the role of chance in creation and creativity than as a confirmation of the acute pointlessness of life that suddenly becomes clear to a seventeen-year-old. (Both Camus and Sartre were Frenchmen and literary writers, with the Surrealists as part of their intellectual antecedents: so the idea of the contingency of existence carrying an echo of the joyously accidental provenances of creativity can’t be entirely dismissed. What in Camus and Sartre is tragic affirmation is preceded, in Breton and Aragon, by a sense of release regarding the same conditions of chance in relation to creativity.)

Much of the academic interpretative apparatus around modernism still carries that teenage passion: it sees fragmentariness of form, Beckett’s minimalism, and Kafka’s parables – to take three examples – as allegories of the twentieth-century human condition. That is, its readings are mimetic, its meanings metaphysical. It largely ignores the physical.

*

The scenario I’ve sketched above would vanish by the mid-eighties with the upsurge of the ludic. Theory, postmodernism, the global novel: these would render the absurd and the existential obsolete, just as it had made a particular spatial sub-tradition within modernism – the view from the window in the apartment – marginal.

In my life, too, a change was taking place: it coincided with my parents moving to St Cyril Road in Bandra after my father’s retirement. It led to me discovering, during my visits back home from London and then Oxford, the flowering in these lanes on the outskirts of Bombay. For me, too, it became necessary, by the time I was twenty three or twenty four, to leave the absurd behind. Thinking back, it wasn’t as if I was really aware, from the early to mid-eighties, of the changes to do with the postmodern novel, or with the poststructuralist conception of play. But I needed to abandon a world defined by a sense of the self and its penumbral shadow subsuming everything in its interiority. For me, this interiority was partly the legacy of a teenage misreading of modernism and Continental philosophy. I had to step out. This resulted in a remaking of myself, whose consequence was my first novel, A Strange and Sublime Address, a book unlike the poems I’d been composing from my late teens to the beginnings of my twenties, quasi-modernist testimonies to the tragedy of the contemporary world. The subjects of my novel were not only a house and a street in Calcutta, but joy.

In spite of this embrace of joy and play, my turn was unconnected to the cultural untramelling I delineated earlier, which characterised the new fiction and philosophy. For me it had to do with reading D H Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers. Lawrence’s novel gave me what I hadn’t found in my own misreadings of modernism. At that time – the early eighties – T.S. Eliot was still to fall into disrepute. He was viewed as the founding father of modernism in Anglophone poetry, but, as importantly, his work contained features that could be misread, and which lent themselves to, and, in my mind, converged with the melancholic history to do with the existential and absurd. His use of Dante in the epigraph to ‘The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock’ as well as in strategic insertions in The Wasteland provided an impetus for an allegoric reading of modernist poetry – formally, verbally, thematically – as if it were somehow a metaphysical representation of the human condition. The epigraphs and quotations, especially as they derive from theInferno, set a frame for reading. So did remarks such as these, where Eliot invokes a cultural mimesis that make us see modernism as a symptom, an allegory, of historical or personal extremity: ‘We can only say that it appears likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult. Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity, playing upon a refined sensibility, must produce various and complex results.’

When I was sixteen, and until I was twenty three, I believed modernism was, on one level, a formalist representation of the fragmenting of human, of Western, civilization, and the tragedy of that fragmenting (‘These fragments I have shored against my ruins’). This reading was inextricable from a metaphysical position on value: that it, like meaning or meaningfulness, must come from elsewhere (in this case, it emanated from a unitary Western civilization that was now lost). In Sons and Lovers, I found no attempt to summon an extraneous source of value; there was no civilisational sense of loss. I was astonished by it. Sons and Lovers carried within it a polemic which emerged from its anti-metaphysical position: its writing returned me radically to the significant fact of physicality, the fact of living in the ‘here and now’, and of living this life. Sons and Lovers is an early work, but its polemics are prescient of the provocative claims Lawrence made in a work he wrote not long before he died: Apocalypse, his eccentric gloss on the Revelations, which begins: ‘Whatever the unborn and the dead might know, they cannot know the beauty, the marvel of being alive in the flesh.’ Sons and Lovers is saying the same thing many years before he formulated those words in Apocalypse. The ‘unborn and the dead’ is, among other things, Lawrence’s euphemism for Western tradition and its inheritance; ‘being alive in the flesh’ a reference to a moment in literary history that’s ameliorated by a radical idea of value. This arc is important to me; it enacts an ongoing rejection on behalf of the physical which I first accessed through Lawrence and which I could not access in my misunderstanding of modernism or the existential. This refutation of interiority has to be distinguished from the postmodern and poststructuralist turn.

*

Now, where did Lawrence get this from? Possibly from the Nietzsche of The Gay Science. How important The Gay Science is to literature, as is the Nietzsche that says ‘yes’ to life, who exhorts us, ‘Embrace your fate’! Why is he saying this? Perhaps it might be connected to the fact that – like Lawrence, for whom the encounter with Italy and sunlight was a transformative experience – for Nietzsche too, the idea of Italy and the encounter with it comprise a revaluation. In The Gay Science, Nietzsche speaks repeatedly of Italy, and Genoa. He also refers to the luxury of a summer afternoon. In other words, Nietzsche’s sense of the release from interiority is happening through sunlight. Sunlight is not a metaphor for the enlightenment; it’s a way of speaking about ‘being alive in the flesh’ – physical existence – but it’s also a way of broaching the dissolution of the self upon its encounter with sunlight. When, in Apocalypse, Lawrence exhorts us that ‘whatever the dead or the unborn might know, they cannot know the marvel of being alive in the flesh’, he’s rejecting an extraneous meaning that comes from ‘elsewhere’, and derives its validity from a source, universe, or epoch outside our own. He’s rebutting the kind of superstructure on which not only is religion built, but the idea of meaning too. There are overlaps here with what Derrida made a case for in, say, De la Grammatalogie. But what’s happening with Nietzsche and Lawrence is quite specific and singular, because it involves a particular physical encounter with the sun. Lawrence reminds us in Apocalypse, when pointing out that ‘the mind has no existence by itself, it is only the glitter of the sun on the surface of the waters’, of what the encounter involves: dissolution.

The tradition or lineage of renewal I’m establishing here includes Goethe. Italian Journey, Goethe’s record of his wanderings in and around Rome, Naples, and the Italian countryside, is not only an account of architecture but of weather and of the sun, of the difference of the European South from the Nordic darkness from which value is supposed to derive. The memory of Italy never leaves him. He’s reported to have asked, before he died, for ‘more light, more light’. Apparently, his actual words were closer to: ‘Could you pull down the second shutter so that more light might come in?’ That’s a very specific instruction. Tagore, in the 1890s, when he’s in his thirties and journeying up and down the Padma on a houseboat, overlooking his father’s estates, writes to his niece Indira Devi, ‘Like Goethe, I want more light, more space’. Goethe is probably invoking Italy on his deathbed, attempting to return to that sunlit moment. Tagore’s memory adorns Goethe by adding space. ‘More light, more space’ – space takes us back to the self’s dissolution into emptiness. So light (which we can only perceive within space) and emptiness are connected both to each other and to the self’s dissolution, while simultaneously affirming physical existence. This is an unrecovered tradition in the West which counters Western metaphysics. Its origins are uncertain, but it goes back at least to Diogenes. Here is a philosopher who instructs Alexander (when he goes to him to honour him and asks, ‘What can I give you?’), ‘Could you stand back? You’re blocking the sunlight.’ This is a gesture toward all the traditions to which sunlight is not a pure metaphor for enlightenment but a reiteration of the immediacy of the physical now and the dissolution of the psychological world of value (‘What can I give you?’). Diogenes’s response is unhesitant because the rejection of the metaphysical, of meaning that comes from another source (and which other source of meaning might be more powerful than the Emperor?), is an urgent matter before the unmediated quality of sunlight.

In Tagore, the exclamation to do with ‘more space, more light’ must be viewed in the context of what’s often, where he’s concerned, a Nietzschean position on saying ‘yes’ to life. The first two lines of his song ‘jagate ananda jagnye amar nimantran,/ dhanya holo, dhanya holo manaba jiban’ (‘I’ve been invited to the world’s festival,/ Human life has been blessed’) appear to contain a startlingly egotistical observation: they actually comprise an assertion. There’s an odd implicit hiatus between the first and the second lines, so that they could function as independent statements about ‘embracing [one’s] fate’: ‘I’ve been invited…’; ‘Human life is blessed’. Tagore doesn’t even bother to use ‘so’ or ‘therefore’ – tai in Bengali – at the beginning of the second line to connect it, explanatorily, to the first (ah, so that’s why human life is blessed – because I’m here); he could have, easily. Both lines become standalone proclamations about the miraculous contingency of ‘being here’, ‘alive in the flesh… only for a time’. But to believe that one’s been invited to participate in existence, and to call existence a ‘festival of joy’ (Tagore composed the song in 1909), is an extraordinary as well as an extraordinarily obdurate thing to say for a man who’d suffered many untimely bereavements in his family. There was his wife Mrinalini’s death in 1902, his daughter Renuka’s in 1903, and his younger son Samindranath’s in 1907 of cholera at the age of 10. Tagore’s song is the most unexpectedly Nietzschean instance of poetry saying ‘yes’ to life. (So, in Thus Spoke of Zarathushtra: ‘Have you ever said Yes to a single joy? O my friends, then you have said Yes too to all woe. All things are entangled, ensnared, enamoured…’ In another song by Tagore that I know because it was my mother’s first recording, something like Nietzsche’s disorienting insight – ‘then you have said Yes too to all woe – is presented in a variation: ‘dukhero beshe esechho bole tomare nahi doribo he./ jekhane byathha tomare sethha nibido kore dharibo he’ – ‘I won’t fear you because you’ve come to me in the guise of sorrow./ Where there’s pain, there I’ll clutch you intimately’. )

*

A great number of Tagore’s songs, in one form or another, praise light. Light is not only synonymous with consciousness, but with the contingency – the chance occurrence – of being alive. To acknowledge light is also an act of affirmation. How does this love of light come to one who belongs to a climate in which it’s freely available? Shouldn’t one, in such a context, cease to notice it? Maybe we who live in countries such as the one Tagore and I belong to – where there’s more of the sun than where Nietzsche or Goethe or Lawrence lived – still develop, at a certain point in our lives, the same sense of being a migrant, a visitor, in the way Nietzsche did when he was in Italy. That is, we, who live in climates that are less dark, still can’t take the sun for granted. Maybe it’s just the interruption of night – I can’t vouch with certainty for the reason – but, at some point, like migrants, we become aware of the sun. Historically, as we notice in the early Sanskrit texts, the poets began to praise it in direct relation to the fact of existence.

I place myself in that tradition. Unlike the global novelists who left behind the melancholy of the absurd – often in the interests of the ‘play’ which was so wonderful in Derrida but took on a slightly sterile expression in postmodernity – for me there was something else: I was allying myself with another lineage by the mid-eighties (possibly because my student days in London hardly had any summer days in them), involving sunlight.

*

This brings me, finally, to two shifts in fiction and in reading – instances of critique – that defined the nineties. These were significant shifts, I think, but never clearly mapped or described.

The first had to do with nostalgia. I think that, in the time of the global novel, there grew in many a longing for a value that emanated not from the energy of globalisation and the free market, and the fiction it was generating, or from the polyphony of the postcolonial novel, but from a European idea of seriousness. Let me discuss, very briefly, three novelists whose reputations represent this longing; then move swiftly to three other writers connected to what I have been saying about sunlight. All of this happened from the nineties to the early twenty first century. The first three novelists – W G Sebald, J M Coetzee, and Roberto Bolaño – emerged in a particular way, the reputations occasionally related to posthumousness, untimely death, or silence: in concordance with our desire for something from the prehistory of the global novel. To be perfectly clear, I’m not talking about their achievements, but the manner in which they were often read and valued.

Sebald seems to be prized primarily as an impossibility: that antediluvian beast, the European modern. Susan Sontag sets the tone in the two questions with which she begins an essay – an act of championing crucial to the shift mentioned above – published in 2000 in the Times Literary Supplement: ‘Is literary greatness still possible? Given the implacable devolution of literary ambition, and the concurrent ascendancy of the tepid, the glib, and the senselessly cruel as normative fictional subjects, what would a noble literary enterprise look like now? One of the few answers available to English-language readers is the work of W. G. Sebald.’ The adjective she uses to describe the ill-fitting nature of his enterprise is ‘autumnal’. It’s no surprise, then, that, for Sontag, Sebald is powerful at this moment within the flurry of global Anglophone publishing because he’s ‘both alive and, if his imagination is the guide, posthumous’. His provenance is decidedly European in a classic twentieth-century sense: his ‘passionate bleakness’ has a ‘German genealogy’. This essay is a vivid testament to Sontag’s own millennial yearning. Her essays on other Europeans – Barthes, Benjamin – are extraordinary portraits of temperament: both of personality and of an age they might embody without intending to. Her piece on Sebald is as much about the impossibility of Sebald as it is about him. It articulates an anachronistic need – unaddressed by the triumphalism of the postmodern and the postcolonial – for the European’s sense of tragedy. Of course, Europe is actually irrelevant. Unlike Sontag’s other essays, she’s less concerned with Sebald’s ‘genealogy’ than – through the compulsions of her need – with his singularity.

J M Coetzee satisfied a different, and equally profound, requirement, and one that seemed to have no place in the ethos of the literature of globalisation: that of a person who, in the midst of extreme politics, should either be completely silent or speak only in figurative language. Coetzee is, for us, Coetzee precisely because he’s not Andre Brink or even Nadine Gordimer, because he refuses to speak in their language and terms, or in a directly interventionist way. Asked to address a crowd of more than a thousand at the Jaipur Literature Festival, Coetzee refused to either say anything or engage in conversation. Instead, he read out a story before the rapt audience. Coetzee satisfies the crowd’s deep longing – a residue of modernity – for silence and allegory in a literary universe that, since the eighties, gives a political meaning to polyphony, to the act of ‘giving voice’ to something. The value of the kind of gesture now synonymous with Coetzee is extraneous to his actual work. It’s seemingly out of sync with the time, and appeals to a seriousness within ourselves that’s out of sync with globalisation.

The third figure, Roberto Bolaño, reminds us – inappropriately, in the new millennium – of a tradition to do with failure, elusiveness, and a resistance to the sort of ‘boom’ that Marquez and other practitioners of the global novel came to represent. Bolaño’s world – often to do with obscure little magazines and the intensity of the literary in marginal locations – descends from Borges and Pessoa, weird Anglophile writers, whose tonality, as I said at the beginning, is unclassifiable, cannot be part of any boom, and actively militates against participating in a tradition of national characteristics. Pessoa, of course, remained largely invisible as a poet during his lifetime; and even his posthumous fame is based on the invisibility of Pessoa, since we can’t say who this seemingly ordinary person, divorced from the heteronyms through which he wrote poetry, might be. Bolaño became famous in Latin America just when he was dying in 2003 at the age of fifty. His fame in the Anglophone world – related to this anomalous need for invisibility in the midst of visibility, for failure where writing was newly, and exclusively, in union in success – came later. According to Larry Rohter in the New York Times ‘Bolaño joked about the “posthumous”, saying the word “sounds like the name of a Roman gladiator, one who is undefeated”‘.

In what way these writers’ works perform in the traditions they’re implicitly or openly associated with is another matter, and not my concern here. Nor am I going to dwell on whether they bring back to the contemporary world the legacies of Benjamin, Kafka, or Borges. Their reputations satisfy a counter-need in the ethos of the global novel; and those reputations exist in the same space in which the global novel does. They now exemplify a type of singularity, prickliness, and recalcitrance – very different from the loquaciousness of a Rushdie or the exuberance of Marquez – created within, and fashioned by, globalisation.

*

I end this ‘possible history’ with four people connected, for me, with a quiet reassessment that took place in the world, or at least in me, in the nineties. It was a time (we have forgotten this now) when we discovered that some artists – especially those we hadn’t thought of in that way – loved sunlight. The first comes from the very centre of that older tradition, and carries my sense – maybe misprision – of what the absurd is. The occasion was the posthumous publication of The First Man by Camus. The book appeared in France in 1994, and in Britain in the following year. It was out of place in at least three spheres: his own sphere of stoic despair; in the dominant tone set in the eighties by Grass, Marquez, Kundera, and Rushdie of textual, cultural, and political exuberance (and play); and in the alternative tone of a paradoxically postmodern modernism being established then by Sebald and Coetzee (Bolaño would come almost a decade later), of melancholy, reticence, and posthumousness. The posthumous nature of The First Man couldn’t be fetishized: it confirmed not the author’s tragic attitude to existence (as Sebald’s death did) but a startling refutation of the deep metaphysical unease that was synonymous for many with his work. The refutation had less to do with post-structuralism’s critique of ‘Western metaphysics’ than with the sun. It was extraordinary to find that Camus had a body, and that he was aware of it. The awareness arose in The First Man the moment – as with Diogenes – sunlight touched the skin. This is an acknowledgement of the sun quite different from – in fact, it’s a rebuttal of – the allegorical colonial ‘heat’ of The Stranger: ‘It was a blazing hot afternoon.’ In The First Man, sunlight makes the narrator conscious of Paris (the home of the human as intellectual) as a place of exile, of his homesickness for Algeria and his love of existence, just as Nietzsche was moved to embracing his fate after his experience of Italy:

Jack was half asleep, and he was filled with a kind of happy anxiety at the prospect of returning to Algiers and the small poor home in the old neighbourhood. So it was every time he left Paris for Africa, his heart swelling with the secret exultation, with the satisfaction of one who has made good his escape and his laughing at the thought the look on the guards’ faces. Just as, each time return to Paris, whether by road or by train, his heart could sink when he arrived, without quite knowing how, at those first houses of the outskirts, lacking any frontiers of trees or water and which, like an ill-fated cancer reached out its ganglions of poverty and ugliness to absorb this foreign body and take him to the centre of the city, where a splendid stage set would sometimes make him forget the forest of concrete and steel that imprisoned him day and night and invaded even his insomnia. But he had escaped, he could breathe, on the giant back of the sea he was breathing in waves, rocked by the great sun, at last he could sleep and he could come back to the childhood from which he had never recovered, to the secret of the light, of the warm poverty that had enabled him to survive and to overcome everything.

To read this passage in 1995 was to register, with shock, what it had made newly available. ‘His last novel luxuriates in the… sensuality of the sun,’ said Tony Judt in The New York Review of Books. ‘Nowhere else in Camus’s writing is one so aware of his pleasure in such things, and of his ambivalence toward the other, cerebral world in which he had chosen to dwell.’ Judt hints at, but doesn’t fully explore, what the ‘escape’ from Paris described above constitutes, and what it means both to the legacy of continental philosophy and to the ubiquity, at the time, of the global novel. I’m not dismissing the latter, and nor am I negating the importance of the Derridean critique I so admire. But here is something else, which I’d encountered when I’d read Sons and Lovers; a lineage opened up surreptitiously in the nineties with the discovery of The First Man. The second node in this lineage resurfacing at the millennium’s end is represented by Orwell’s essays. Their rediscovery qualified the allegorical Orwell: it took our gaze away from the metaphysical terrain that dominated our idea, from school onward, of the ‘Orwellian’, as exemplified by the slightly absurdist proscenium space of Animal Farm and especially 1984. With the essays, it’s not only a question of sunlight – it’s a question of love. I suppose this is the word I’ve kept out of my discussion, which Camus mentioned in the context of his numbness in Paris and his love for Algeria and for the sun. Orwell’s love of everyday aspects of English culture included even its food. At one time, to champion English food was to take up a shockingly provocative position that, in Orwell, becomes an embrace of the physical and the un-grandiose, of ‘all things… entangled, ensnared, enamoured’. English tea, English food, English second-hand bookshops, ‘dirty’ postcards on an English beach – the very joyous absurdity of Englishness becomes an argument against the absurdist, metaphysical, parable-like shape of 1984. As with Camus, the reappraisal of Orwell, who expended no more than five to six or seven hundred words on these subjects, was unexpected and sank in slowly. Its significance to the post-globalisation era is still not clearly delineated.

My third reassessment is a personal one, related once more to my search for a refutation of the metaphysical, but in a way that had little connection to the various critiques raised by Derrida, Said, and postmodernism. I realised – again, in the nineties – that Ingmar Bergman, whose cinema, when I was a teenager, seemed integral to the penumbral darkness we took so seriously in the seventies, was not so much a proponent of allegory as an artist of physical existence. I had seen Smiles of a Summer Night, but somehow not noticed it. When you’re responding to allegories of the human condition, you fail to see the physical. It was as if I’d watched Smiles of a Summer Night daydreaming about what the word ‘Bergman’ signified, and missed the carnality and mischief, Bergman’s promiscuous love of sunlight and joy. Once I began to notice these details in the film in the nineties, it was if the lineage of the sun, and of physical, sensory experience, had revealed itself – as in Camus – in the heart of the metaphysical and of the dark. I saw how much of a presence sunlight, and the joy it bestowed upon the moment, had been in Wild Strawberries; again, it had passed me by completely when I’d viewed it, in the late seventies, as the work of an agonised allegorist dealing in symbols. Even The Seventh Seal, about death, medieval mythology, and the winter, was, I now saw, essentially a comic work, its bleak but clear light illuminating the dance of death at the end as it would a dance of life.

My final example of reassessee is the author who was recruited, from the start, ever since his posthumousness defined the twentieth century, as the arch parable-writer and prophet of absurdity: Kafka. It’s only in the last fifteen years that I’ve paid more attention to the anecdote that relates how the friends who listened to him read from his stories doubled up in laughter at what they heard. About two decades ago, revisiting ‘Metamorphosis’, I marvelled at Kafka’s devotion to physical detail. I marvelled, too, that I’d ignored these details on earlier readings of Kafka’s writing as allegory. The appeal of the metaphysical had made his exactness redundant. Here is an account of Gregor’s sister trying to figure out what might appeal to her brother after his appalling transformation:

She brought him, evidently to get a sense of his likes and dislikes, a whole array of things, all spread out on an old newspaper. There were some half-rotten vegetables; bones left over from dinner with a little congealed white sauce; a handful of raisins and almonds; a cheese that a couple of days ago Gregor had declared to be unfit for human consumption; a piece of dry bread, a piece of bread and butter, and a piece of bread and butter sprinkled with salt.

The juxtaposition of bones, sauce, bread, and newspaper, the dry and understated poetry of the list, the hilarious but wrenching double-edged positioning of the cliché, ‘unfit for human consumption’, comprise, together, an example of how a sentence might embrace fate. Once I discovered it, I found Kafka untethering himself from the remnants of teenage interiority.

First delivered as a talk at the symposium on ‘Reassessments’ in 2017 and then collected in The Origins of Dislike (2018).