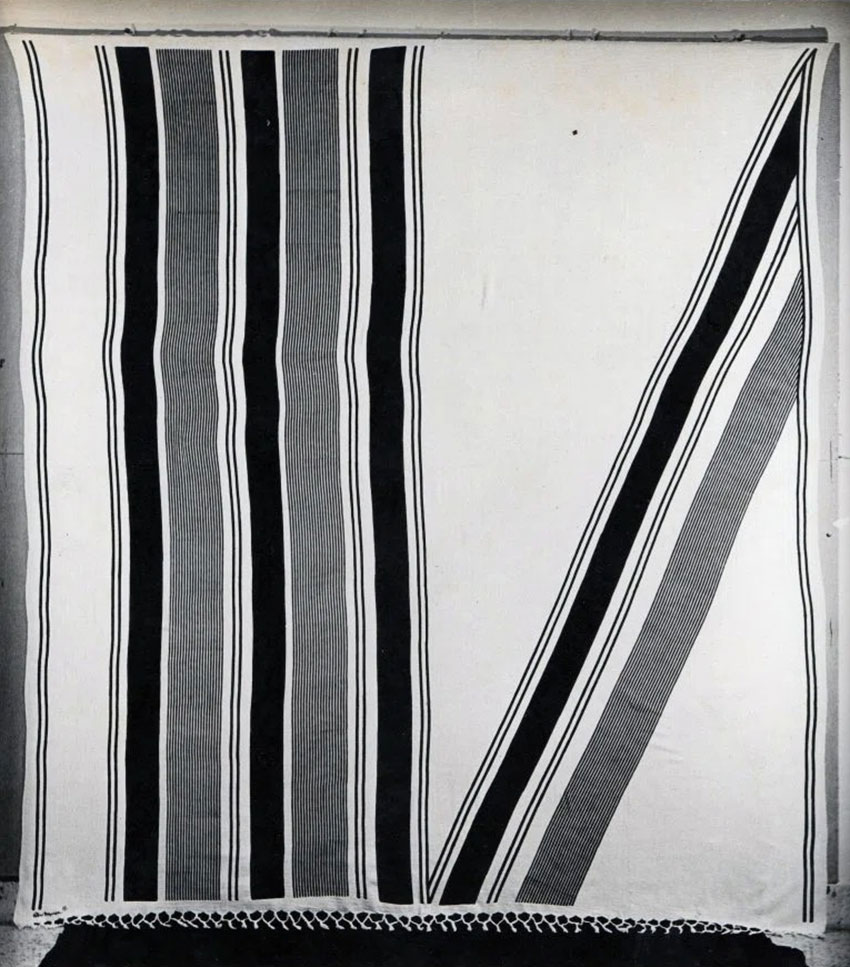

Rasta, 1966-2000, bedsheet design for Fabindia, by Riten Mozumdar. Photo courtesy heirs of Riten Mozumdar.

On Not Mentioning the Modern: Mission statement

The British Council had arranged some sort of colloquium in the early years of this millennium, bringing academics, writers, and artists together at the South Bank Centre in London. At one point, we were, like children, separated into small groups in order to discuss possible themes for future conferences. After listening to the others in my group, I murmured ‘modernity’, mainly because Indians never talked about it, and it was treated as property exclusive to the West. The moment I said the word, a well-known Indian sociologist in the group flinched and said: ‘No, no, not modernity.’ It was like witnessing a religious experience; the overstepping of a sacred line.

I have wondered before and since that moment why modernity, the modern, and modernism – terms that are by no means interchangeable, but which are related to each other – have largely vanished, in India, from critical discourse and the quest for self-knowledge. There’s not only a deep hostility to, and nervousness about, the modern; it has, in a sense, slipped out of language. This slipping out has occurred, to a large extent, in the last forty years, with the rise of an Anglophone class and an Anglophone humanities. For instance, the counterpart of ‘modern’ in Bengali – adhunik – has a historic and cultural specificity: it isn’t a taboo idea.

How do we explain this? Partly it has to do with the view that ‘modernity’ is foreign, or even an offshoot of colonialism. We were on our way to creating an indigenous modernity, this argument goes; then colonialism forever interrupted that process. ‘Colonial modernity’ is a definition of a pervasive reality that established itself in India from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, but it’s also an implicit reminder of what never happened: a homegrown, authentic modernity.

Whatever the reasons – and they are too many to discuss here – for the sociologist’s nervous outburst, it means we hardly have a vocabulary, at least in English, to talk about very substantial aspects of our history: about our own languages and their role in the emergence of the modern; about our cinema, music, literature, and art; about our urban spaces and architecture; about ourselves. What I’m saying here pertains not only to India, but to all parts of the world that were once colonised, which moved from a state of premodernity to being colonised, and then from nationalism to postcolonialism and globalisation, all without having experienced, putatively, modernity.

To speak today about ‘non-Western modernities’ is an academic exercise – the job of conferences. What this symposium wishes to enquire into is a process of forgetting and how and why it occurred; the experience of remembering; and the possibility of creating a language both to acknowledge a legacy and describe a reality.

Amit Chaudhuri

Please click the link: On Not Mentioning the Modern: Schedule to check the schedule for 25th and 26th February, 2022.